At the end of last semester, Assistant Professor of English Kelly Carlisle decided to talk to the head of the English department to ask if the department could provide some start-up money for a new project. Once she obtained approval and funding, Carlisle invited four rising seniors ““ Michael Garatoni, Spenser Stevens, Mallory Conder, and Paul Cuclis ““ who had taken classes with her and whom she knew to have an interest in publishing and creative nonfiction writing, to join in on the project.

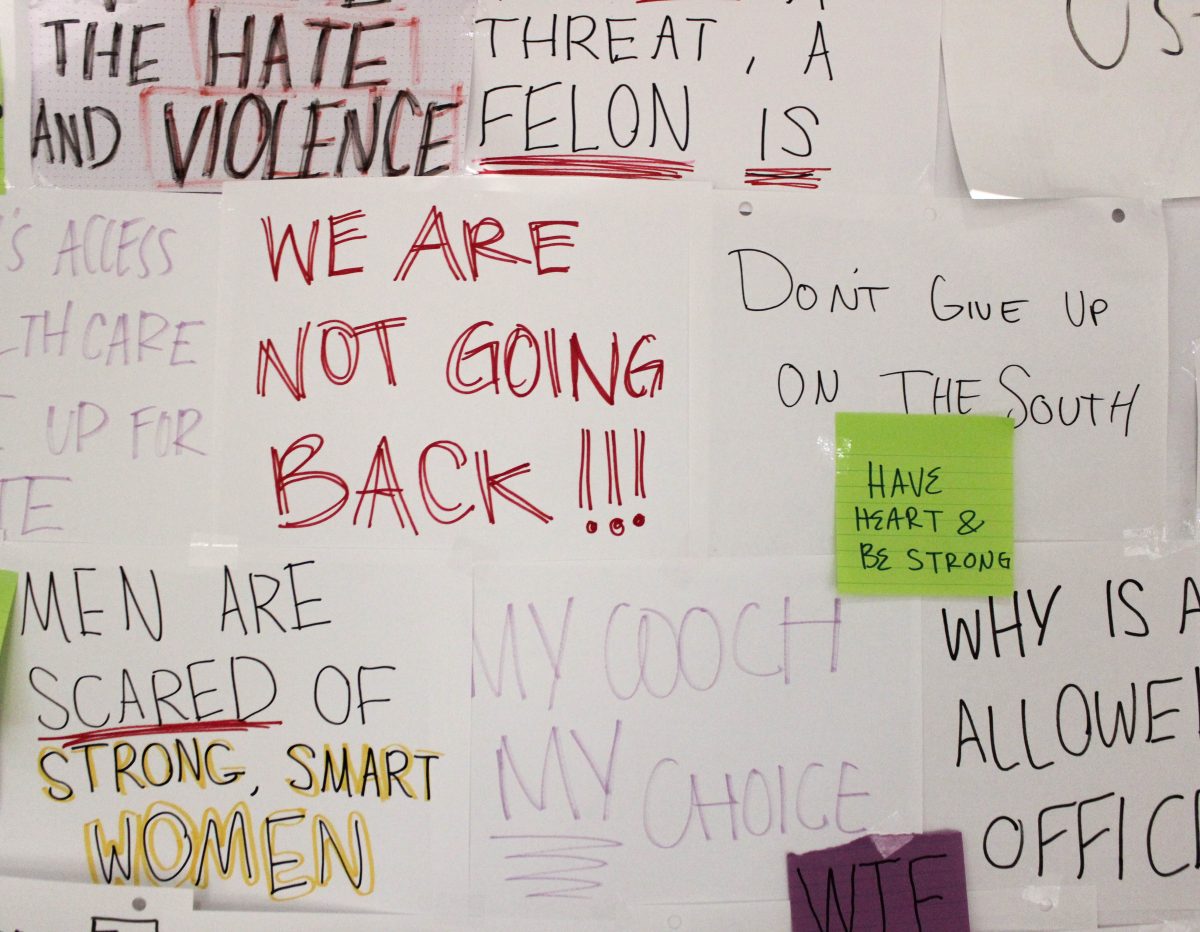

The undertaking, which she revealed to be the production of a national literary magazine, differs from Trinity’s pre-existing literary magazine in a few major ways. Firstly, while the Trinity Review publishes anything from memoir to fiction to poetry, the works to be published in the new publication, called 1966, are of a specific branch of nonfiction writing that is defined by its research component.

“The magazine itself is named after the year in which In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, a very famous article by Gay Talese called “Frank Sinatra has a Cold,” and this other weird book called Oranges by John McPhee were all written,” said Carlisle, who teaches Trinity’s creative nonfiction courses.

Each of these works played a part in beginning New Journalism, which was a movement popularized in magazines like The Atlantic Monthly and The New Yorker in the 1960s and 1970s.

“The idea behind New Journalism is essentially creative nonfiction with a strong research or investigative component, and that is what 1966 will publish,” Carlisle said.

The developing literary magazine will publish works that are along the same concept as the New Journalism movement as it continues to progress.

“There are literally thousands of literary magazines around the world, and many of them are already engaged in specialization, and, in order to stand out, 1966 is going to specialize in a particular subset of the nonfiction genre,” Carlisle said.

Many literary magazines focus on nonfiction memoir or personal essay, but Carlisle and the involved students hope to focus more on experimental works of nonfiction.

“Since we’re just starting out and don’t have to work to maintain our existing audience, we can be open to the less traditional. The New Yorker, for instance, can’t publish the weird stuff because they’re concerned with making money. That isn’t our concern, so we can publish the weird stuff ““ graphic nonfiction for example,” Carlisle said.

1966 also differs from the Trinity Review in that the work published by the national literary magazine will not be Trinity-student produced.

“This work will be from writers all over the country, conceivably the world. Also, where primarily Trinity people read the Trinity Review, we’re hoping that 1966 will have at least a national audience,” Carlisle said.

The other major difference between 1966 and the Trinity Review is that, at least for now, 1966 will be published exclusively online. This difference stems from the fact that the Trinity Review has been published for decades, while 1966 is just starting up.

Ultimately, Carlisle hopes that more students can be involved in 1966’s production. The four students involved are taking an independent study course with Carlisle and are responsible for getting the publication going. They will be soliciting authors for work, improving upon the existing website (www.1966journal.org) and making all major aesthetic decisions, among many other publishing-related tasks.

“Eventually, assuming this first year of production goes well, working on 1966 would definitely be open to more people,” Carlisle said. “The big thing for someone who wants to work on 1966 is that you have to have an interest in the literature. If students are interested in publishing generally, though, the Trinity Review is also a good option for students who want to be more attractive to potential employers in the publishing industry.”