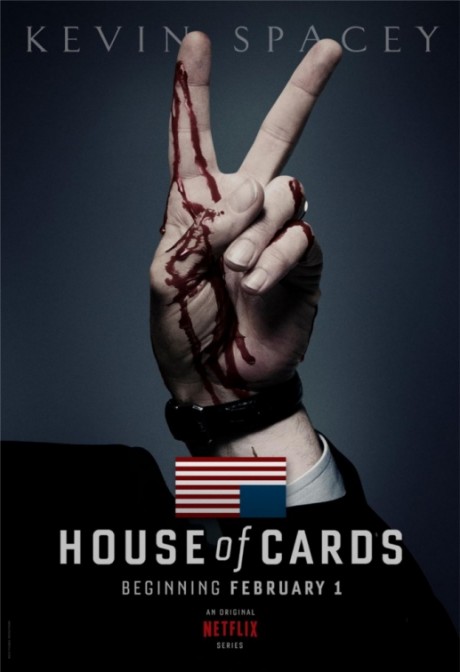

Netflix’s first original series, “House of Cards,” stars Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood, a ruthless but calculated Congressman serving as the Majority Whip (meaning he is in charge of making Democrats vote in conjunction with the rest of the party) and a powerful ally in the recent election of the President Elect, Garret Walker (Michael Gill). Francis believes his assistance has assured him nomination for Secretary of State. Unfortunately for Francis this is not the case once President Garret takes office, sparking Francis to begin gathering allies and collecting favors to exact his revenge against the administration. The show is exclusively available online with a subscription to Netflix Streaming.

Kevin Spacey begins his first foray into the world of dramatic television with a shocking and controversial scene. Spacey’s Francis “Frank” Underwood awakes to the sound of a car in the neighborhood hitting something and then peeling away. Frank is first on the scene before his other neighbors join him. He finds a neighborhood dog that was struck by a vehicle and bends down to find the dog suffering. This begins the first instance of a visual and narrative trope that becomes a calling card for the series. Frank addresses the audience directly before “putting the dog out of its misery” and delivers the following Shakespearean-esque speech concerning the two different kinds of pain:

“There are two kinds of pain, the sort of pain that makes you strong, or useless pain, the kind that’s only suffering. I have no patience for useless things. Moments like this require someone who will act, do the unpleasant thing, the necessary thing.”

After giving into Netflix’s unconventional release schedule (all 13 episodes were released at midnight on Feb. 1st) and somehow consuming a little over 12 hours worth of TV over Super Bowl weekend, I feel that David Fincher’s (the series’ executive producer and director) opening quote for the series is incredibly appropriate to set the tone what’s to coming. The quote describes the world in which the characters live and make the hard decisions they face every day. That being said, the series itself ironically works beautifully to counter Frank’s point about “useless” or “unnecessary” pain.

It may be due to the lack of regulation, lack of broadcast norms or even just lack of network notes, but “House of Cards,” much like the process it takes to build such a structure, is “painfully” and “unnecessary” slow at times. According to Frank’s quote this would make the show essentially useless, but instead I believe this is the key to the shows success as a modern and captivating drama, easily comparable to any of the other high concept dramas held in recent critical acclaim. Although the show’s characters could be seen as being “Sorkin” in terms of their heightened vocabulary and tendency to use English from an almost ancient era (Spacey’s character especially), they are instead void of any of the “walk and talk,” million words per minute tendencies that typically come with that territory. Characters even take their time entering the room, beginning the conversation and especially getting to the point. Plot lines that could be wrapped up in a single episode take several, some scenes get extended into several painstaking parts and even the title sequence is beautiful, but ungodly long, at almost two and a half minutes. Slow as molasses could easily be used to describe significant parts of the series, but instead of being a major complaint, this fact is one of, if not the strongest, aspect of the series. Like molasses though, every slow scene is incredibly sweet and enjoyable as the scene drips slowly off your fingers, giving more time to enjoy more of the beautiful and stylistically shot scenes, not to mention letting us fully enjoy the powerful interactions between the incredibly nuanced and captivating characters. Frank may not agree with the beautifully slow pacing of the show and would want it smothered out of uselessness, but getting lost in Fincher’s meticulously slow and dark political thriller and painfully dark plotline is a treat for anyone who would appreciate a modern television drama.

Beyond its uniquely downtempo pace, the show exhibits many of the other same factors that are cited in the greatness of other great modern dramas. Spacey’s Frank Underwood is an incredibly strong likeable antihero in much the same vain as Tony Soprano, Walter White, and even Don Draper. Even Robin Wright’s Claire Underwood is clearly of the same archetype from these shows, playing the role of the supportive but strongly independent wife that realizes she must also look out for her own interests as well. Overall, whether by chance or intention, Netflix has created a drama that fits in perfectly with “Breaking Bad,” “Mad Men,” and even other premium cable dramas such as “Game of Thrones” or “The Sopranos” in almost every way. From its questionably moral protagonists, dark and brooding visual styles, down to even the narrative structure of seasons and even an emphasis on drug and alcohol abuse and addiction, I will be greatly surprised to not see the show join the ranks of the usual Emmy nominees in the near future.

Overall, Netflix lucked out with its first foray into original programing and will hopefully be critically rewarded for such a powerful contribution to the modern dramatic landscape. The characters, plotlines, visual style and even casting are all on par or even superior than any of its “on-air” counterparts. Apart from a few reservations I have about a potentially “weak” ending of the first season, of which my complaints are only minor and may be more frustration that my joyride with the show was over, I highly recommend at least trying an episode or two, if not binge watching the whole season next time you are on Netflix.

Overall Score: 9.0/10