On April 4, 2011, the U.S. Department of Education and its Office for Civil Rights issued the “Dear Colleague” letter to institutions of higher education around the nation, including Trinity University, as an extension of the Title IX legislation, equalizing education for women. Along with a new administrative position, colleges and universities across the nation, including Trinity, have also been mandated by the letter to investigate all reports of sexual assault. Since the “Dear Colleague” letter has detailed how universities should deal with sexual assault, instances of misconduct, rape and university fault have been recorded across the nation, bringing skepticism from administration, law enforcement and public officials.

In accordance with the letter’s guidelines, Trinity instituted a Title IX coordinator, distinguished professor and chair of the chemistry department Steven Bachrach, to handle cases of sexual assault and other Title IX-related issues on campus. Bachrach, along with David Tuttle, associate vice president of student affairs and dean of students, are the main administrative correspondences in the case of a sexual assault on campus.

“First and foremost, we explain [the survivor’s] options. There are options to go through legally, with TUPD and SAPD, and options on campus in terms of living space and contact with the other party,” Tuttle said. “Then, to really strategize with the accusing student on considerations of what we would do moving forward. The biggest question being, If we don’t pursue this, will it create potential harm to the community?”

According to Tuttle, there is usually an insufficient amount of evidence to prove a serial rapist scenario on campus, which would warrant a campus-wide notification about the accused student. After contact is made with the accused student, the university determines the necessity of a University Conduct Board hearing, taking into consideration the preference of the accusing student on how to proceed.

The Trinity University Police Department acts to the triage and the investigation side of reports. If approached within 72 hours of the assault, they are tasked with ensuring that the survivor receives proper medical attention, as well as a rape kit, and conducting a medical exam on a suspect, if possible. According to Paul Chapa, chief of university police, he also helps seek an advocate for the victim.

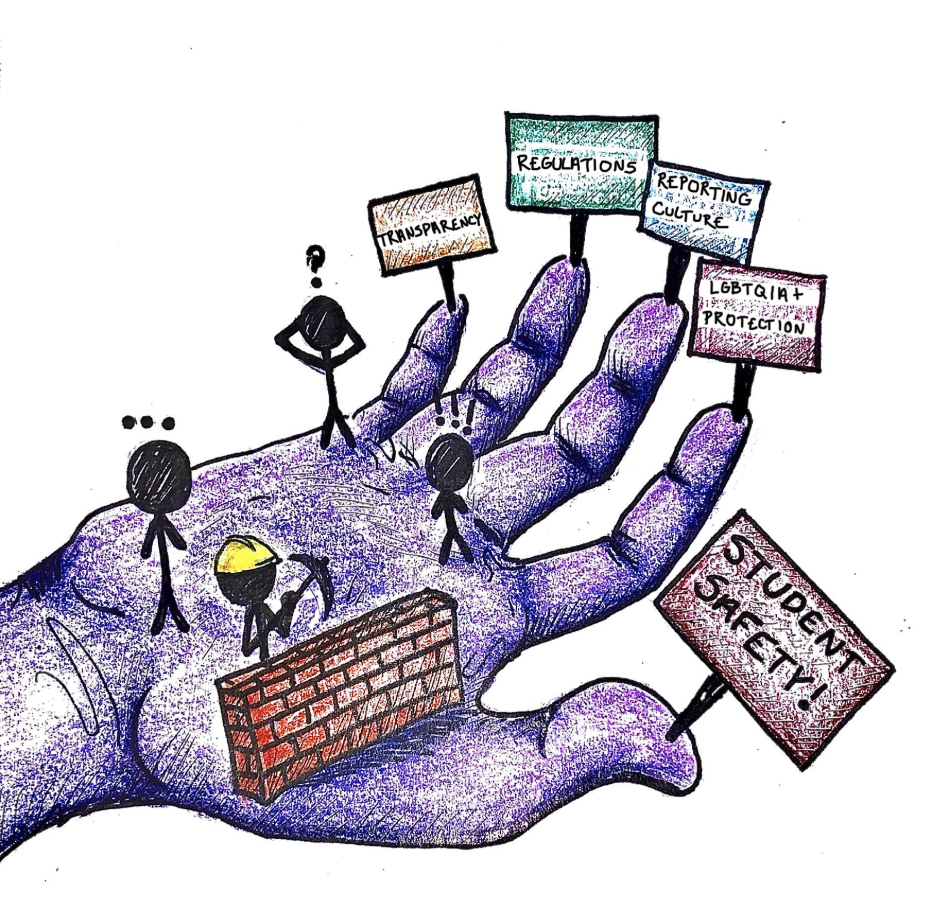

Challenges

However, Trinity is experiencing challenges with receiving and handling reports of sexual assault. According to Bachrach, there is concern that the mandate to investigate reports of sexual assault may reduce the already-low numbers of reports.

“We don’t think it has had any, but we are concerned that it might have a chilling effect on the number of reports in the future,” Bachrach said. “So, we are trying to make sure students understand why we are doing what we are doing. This is to safeguard the entire community. We hope that message is getting out there. It is certainly something we are going to track.”

On top of this possible chilling effect, survivors often do not report cases of sexual assault due to feelings of embarrassment or shame. According to Nicole Castro, 2012 Trinity alumna and coordinator at the Rape Crisis Center in San Antonio, fear of social persecution is an unfortunately common phenomena among survivors.

“The biggest thing you will see, is that victims of rape suffer silently,” Castro said. “While the physical attack itself is horrible, the victim’s first reaction is often that no one will believe them, that it’s their own fault, that they are ashamed that someone else inflicted violence on them. That’s where you see the rape culture affecting the human process of rape survivors.”

Ultimately, it is up to survivors if they wish to pursue the case legally. However, in the majority of cases, survivors choose not to pursue the case legally because either they did not report it in the first place or the instance involved alcohol.

“My guess is a great bulk of them are not reported,” said Krista Melton, assistant criminal district attorney for Bexar County under the family justice section. “I think another issue is a whole lot of cases with college-aged kids, whether at the university or not at the university, involve drinking. And so, a lot of times what happens is the victim may not be able to A) identify the defendant or B) sometimes, they were so drunk, they don’t even necessarily know what happened. So, in cases like that, that makes it very hard, because you then don’t have the victim able to say what has occurred to them.”

According to Melton, the district attorney’s office can still attempt to pursue such cases with the use of secondary evidence or eyewitness accounts to prove whether consent was given in the sexual act. In cases where the survivor is asleep or otherwise unconscious during the sexual assault or its initiation, it is proved that consent was not given. However, there is skepticism about the use of university conduct boards and similar campus tools.

“Do I think the university ought have its own disciplinary proceedings for, basically, failure to conduct yourself according to the university honor code? Absolutely. But I think that sexual assault is an incredibly serious crime, as does your elected district attorney,” Melton said. “So, our view is all of those sexual assaults should be reported to law enforcement.”

According to Bachrach, there are major differences between the legal system and university investigation.

“Our laws, how we adjudicate things, are very different then what would happen in a criminal or a civil case,” Bachrach said. “Just to give you an example, our bar of guilt is a “˜preponderance of the evidence.’ So, there’s a lot of different ways to phrase that “” 50 percent-plus. In a criminal court, it’s “˜beyond a shadow of a doubt.’ Very different levels of adjudication.”

Melton also stated that often the time length of pursuing a case legally is sometimes unappealing to survivors, whereas a conduct board hearing and investigation process takes, on average, six weeks, according to Tuttle.

Prevention

When addressing sexual assault prevention on college and university campuses, alcohol plays an important role. According to Tuttle, that is one of the main challenges facing Trinity.

“If there is a way to create a responsible drinking mentality, then we should bottle that and sell it to other campuses. I just don’t know how possible that is,” Tuttle said. “We can do the Step Up bystander intervention program, but if people are too drunk to watch out for their friends, it won’t make a difference. The one thing we could really do would be to create a culture in which people who host events are the people having the worst time at these events. You need to be sober to monitor your party.”

Along with dealing with drinking, education on consent is a concern. Whether alcohol is involved or not, consent and bystander intervention is a major role in most sexual assaults. According to Texas State Law, an intoxicated individual is deemed incapable of making a decision, so any sexual contact with an intoxicated person is potentially rape. If consent is given by the drunken person, that consent is void by their intoxication. According to senior Kimberly Berry, previous president of Students for the Advancement of Gender Equality, silence should not be interpreted as consent either.

“If she had sex and didn’t intend to and didn’t even say “˜yes’ but was just quiet all night, she didn’t give consent,” Berry said. “Consent is crucial. Consent should be being able to tell someone without feeling pressured/coerced, being comfortable and telling them what you want. You shouldn’t feel uncertain. You should feel good about your decision. So many people say, “˜oh, she cried rape after but enjoyed it during.’ Well, she may have felt super-pressured by her boyfriend to have sex because he keeps asking and is starting to flirt with other girls. False reporting is so low…yet everyone uses that as an excuse.”

According to Bachrach, many cases of sexual assault were preventable by a bystander or witness before the event, and that bystander outreach is a strong source of prevention.

“We are concerned about not enough students standing up and protecting each other. In every case we’ve seen so far, there were a myriad of opportunities for friends to intervene. And that intervention didn’t take place,” Bachrach said. “What does it mean to be a friend if you can’t get off your ass when your friend says “˜get me out of here’? Those aren’t friends, obviously. We need to work on that sense of community.”

Many university plans around the nation emphasize the idea of an intervening bystander as a means of prevention. However, most advocates argue that it is a change in the attitude and culture of a university or community that is necessary to stop sexual assaults.

“Educate students””both the potential victim population and your potential perpetrator population””that this is not going to accepted. This is not how we treat our peers. This is not how we engage in sexual conduct. Period,” Melton said. “And so, my urging to””and I would say this for the entire district attorney’s office, because I know that I can speak on this issue for them, in this sense””we would urge people to come forward with what had happened, because you’re preventing future abuse.”