“How did we get from Hollywood to YouTube? What makes Wikipedia so different from a traditional encyclopedia? Has blogging dismantled journalism as we know it?”

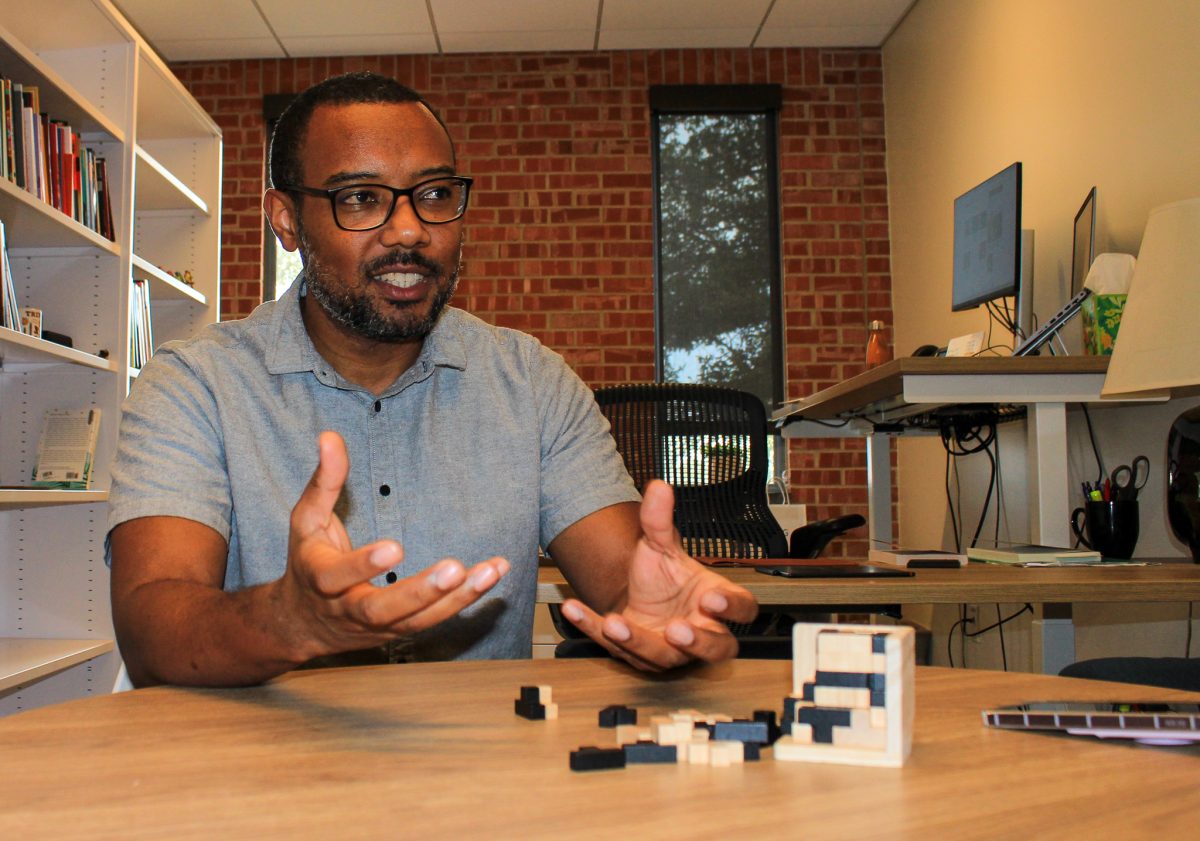

These are a mere sampling of the questions asked by Aaron Delwiche, associate professor of communication, and Jennifer Henderson, associate professor and chair of the department of communication, in their recently published book, “The Participatory Cultures Handbook.”

“In order to be defined as a participatory culture, there must be low barriers for participating and expressing yourself, so almost anyone can get involved,” Delwiche said. “It provides strong support for sharing what you create, some sort of system of mentorship when you get involved and a sense that what you’re doing in this culture is valuable to other people. Whether it’s a cat video on YouTube or a response to some meme going around, there’s a sense that someone cares about what you’re doing and that it will be recognized.”

“The Participatory Cultures Handbook” is comprised of a collection of essays from scholars and artists in all different disciplines, including physics, poetry, philosophy, political science and comic books. Even Henry Jenkins, a well-known scholar and the man who originally introduced the idea of participatory cultures after observing the complex network of fan conventions, immediately agreed to submit an essay for the handbook.

Henderson originally became interested in participatory cultures after teaching a first-year seminar course called “The Fandom of Harry Potter.”

“The class was about the fan community online and in the real world, and how they mobilized for collective action in different kinds of ways,” Henderson said. “I started to look at other fandoms, and I realized this was something a lot bigger than that. We started to identify other participatory cultures and got excited for the potential of it. The book is an interdisciplinary work that involves people working in a lot of different areas using these collective intelligence ideas to solve problems.”

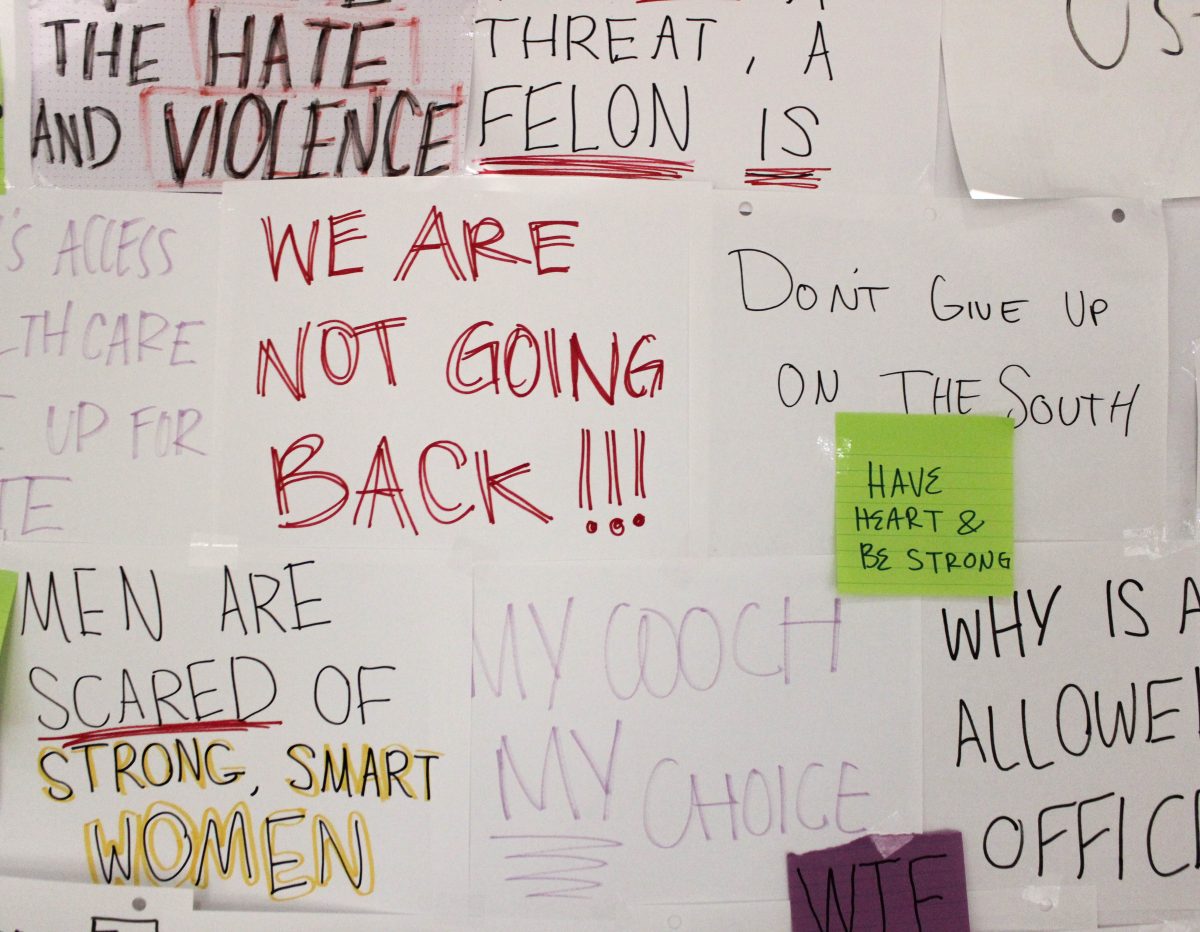

Essays in the handbook touch on myriad different types of participatory cultures and connected themes, such as crisis mapping, Habitat for Humanity, the role of technology and information sharing in authoritarian countries, crowdsourcing, blogging and the part that collaboration and information-sharing play among physicists when they are analyzing the data that comes from the Large Hadron Collider in Sweden.

“Participatory culture has lots of issues associated with it. For example, dissidents in oppressive regimes like Syria use technology to organize and fight back, but when an oppressive regime has access to technology and everything coming into the Internet, that’s scary for the dissidents,” Delwiche said. “We didn’t want to just be utopian about participatory cultures, so we also got people who were critical about it. There are essays by a handful of people who are deeply skeptical about what is going on.”

Participatory culture is increasingly finding its way into university classrooms. More and more often, professors encourage class discussions, group projects and class blogs, all of which are common facets of participatory culture.

“For some of us, our philosophy on education is very much in line with participatory cultures,” said Cynara Medina, visiting assistant professor of communication. “This kind of stuff teaches you the value of being transparent in a classroom, which I think students really appreciate. I am going to point you in the right direction, but I am not necessarily going to tell you this is the right or wrong answer. You are going to discover it on your own in collaboration with others. That is a completely different philosophy than my standing in the front of the classroom telling you what participatory cultures are and then testing you on it. It is just really good stuff.”