When Michelle Bartoniko, “˜08, first arrived at Trinity University, she knew two things for certain: she was going to study abroad, and she was going to major in history. Bartoniko followed through on both of those plans, and she is now the digital content and marketing specialist for Trinity University Communications.

Many students like Bartoniko come to college aspiring to study history. However, some of them end up switching their major to something that is seen as more practical because they constantly hear from their parents and the media that a history degree will get them nowhere in the professional world. One Trinity professor acknowledges this challenge and has helped develop a program that she hopes will encourage students to embrace their passion to study history.

A couple of years ago, Linda Salvucci, associate professor of history, became involved in a project sponsored by the American Historical Association called the Tuning Project. The Tuning Project aims to foster a series of conversations about the study of history and how it can make students lifelong learners who are civically engaged and equipped to be successful in the workplace.

“The idea behind the Tuning Project is to articulate the value of studying history,” Salvucci said. “It’s a nudge for professors to be a little bit clearer on what we do and why we do it, but I think it also serves the purpose of arming prospective history students and history majors with a way of talking about what it is that we do in advanced history courses. It’s a way of talking to prospective employers about what skills you can bring to the workplace and convincing parents who are skeptical about you declaring a history major.”

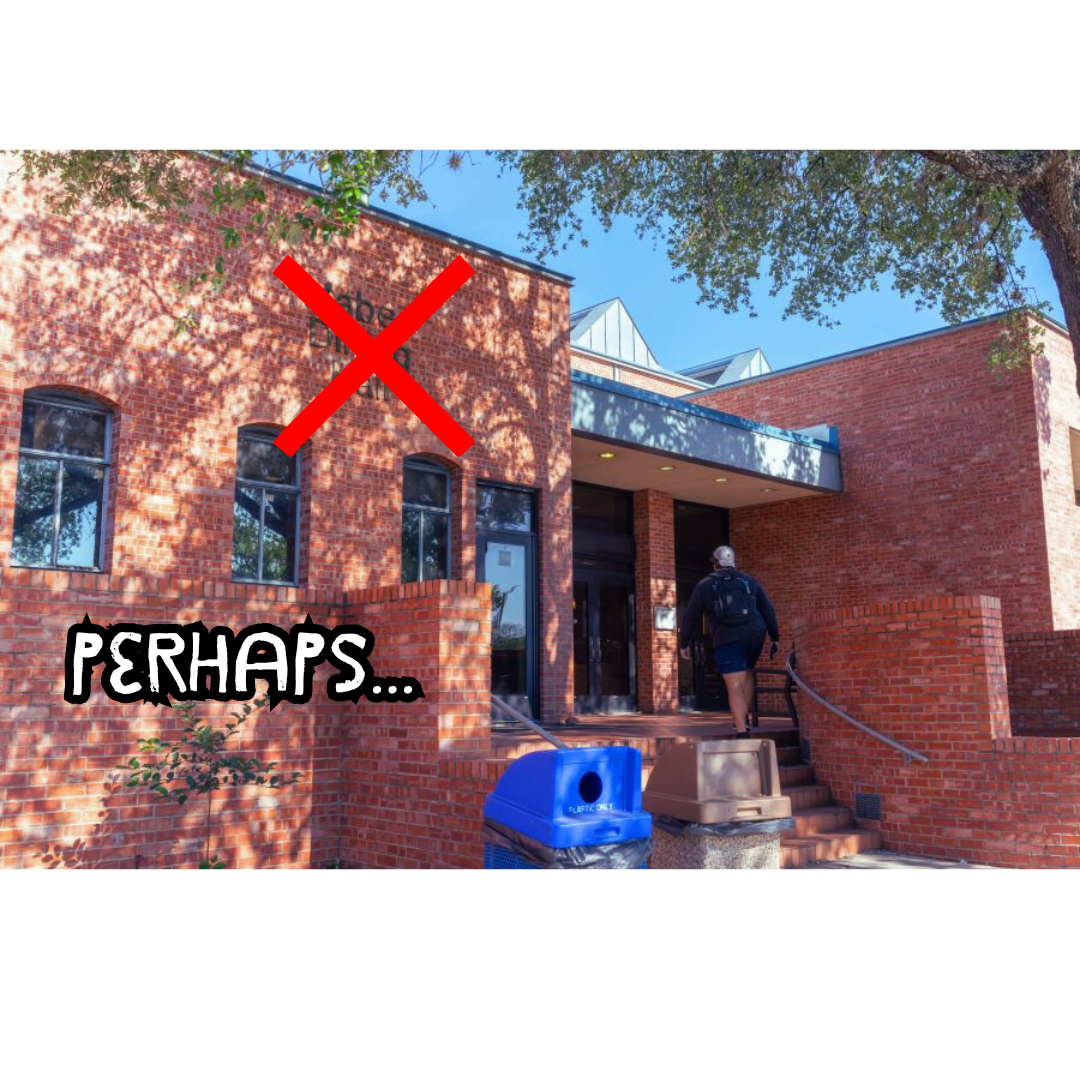

This past Tuesday, the history department, in conjunction with Career Services, hosted a panel in the special collections room on the second floor of Coates Library. The panel consisted of four people who majored in history during their undergraduate careers who went into careers not considered traditional for history majors. Apptly titled “What Can You Do With a History Major?,” the panel sought to reassure history majors and those interested in the field that a history degree is not limiting; in fact, the panelists argued that the study of history teaches invaluable skills not typically found in other majors.

“History taught me how to be an effective researcher. That is something that I think is really important in the workforce today,” said Amy Roberson, special collections librarian and university archivist. “Effective research isn’t just a Google search, and I think a history major teaches you proper research skills that employers really covet.”

Roberson followed that up by stating how history teaches students valuable reading skills.

“You have to read so much material as a history major, and that means reading book after book and being able to synthesize and analyze the arguments contained in those texts,” Roberson said. “Several jobs involve reading multiple reports and the like, and being able to summarize all of that in a concise manner is so important.”

Bartoniko took a more abstract route in describing the value of a history degree.

“You can’t understand the future unless you know the past. I know how cliché that sounds, but it’s true,” Bartoniko said. “A history degree allows you to put together different puzzle pieces in any situation because you have all of the analytical skills necessary.”

Tyson Neal, “˜05, associate vice president for PowerHouse Electrical Services Inc. and Legend Lighting Inc. in Austin, was passionate about history coming into Trinity, but he was never absolutely certain what he was going to do with a history degree after graduating.

“During my first year at Trinity, I took a first-year seminar taught by Dr. Salvucci all about the Alamo. We hit it off because I really love studying the topic of history, and she actually was my advisor during my time here. She helped me overcome my doubts and continue to pursue my history degree,” Neal said.

Neal narrowed down the description of a historian and explained how it applies to the professional world.

“Essentially, a historian is somebody who does two things: you analyze cause and effect, and then you convince people that you’re right,” Neal said.

The National Football League was, in fact, never initially the ultimate goal for Jerheme Urban, “˜03, the new head football coach of Trinity University, when he first started his college career at Trinity.

“I am a south Texas guy who grew up on a ranch, so family history and Texas history were important parts of my life,” Urban said. “I came to Trinity with a passion to impact young people, and I had my eyes on the M.A.T. program. I got a social studies composite degree with a focus in history. I had plans to teach history in high school and coach high school football, just like many of your high school history teachers.”

Although he has not specifically relied on his history degree for several years now, Urban acknowledged that it has played a massive role in the success he has enjoyed.

“There’s no question in my mind that I would not have had the playing career I had without the skills I learned from the history program here,” Urban said. “Let’s face it. I knew I was not the most athletic guy on the NFL teams that I played on, so all of the little things I did counted. The attention to detail when studying plays and time management that the rigors of a history degree taught me really helped me on the field.”

Besides being history majors, all of the panelists also had something in common.

“Something to notice about these panelists is how flexible they are,” Salvucci said. “Life isn’t a straight path. It’s more like a winding road with no definite destination. You have to be open to the opportunities presented to you.”

Twyla Hough, director of Career Services, was also on hand for the panel and pointed out the overall lesson she wanted students to remember.

“One of the biggest things to take away from this panel is that major does not equal career,” Hough said.

Although this panel of history majors did not include any professors, primary school teachers or lawyers, Salvucci hopes to expand the program and include them in future sessions.