By Grace Frye and Jeffery Sullivan

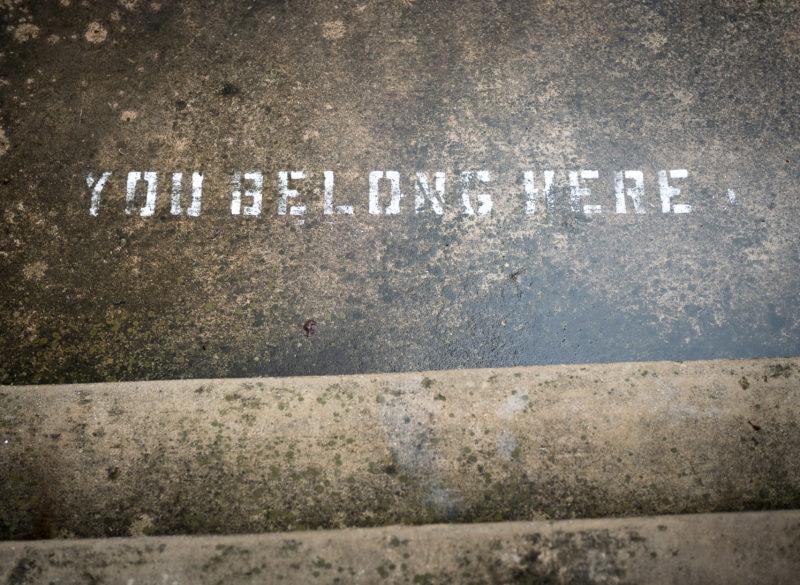

Benjamin Conway made his stencil on an unremarkable weeknight in November. Dressed in inconspicuous clothing and with spray paint in hand, the then sophomore set out on a mission to provoke a conversation about “˜place’ on Trinity’s campus. That night, and many others, Conway not only violated campus vandalism policies, but also sparked an important discussion with three words: You Belong Here.

“I wasn’t really intending for it to be a warm and fuzzy thing meaning if you were grappling with identity that this was supposed to reassure you that you were part of the community,” Conway said over the phone. “It was really sort of a call to action that was about subverting power. Trinity has a beautiful campus, and students didn’t feel a real ownership of place.”

Conway started the night with a tag, that remains today, in the Dicke Smith Art Building studio. Conway said he spent the first night furiously tagging spaces on campus that do not see much activity from students. While Conway worked alone on the creation and tags, he was aided by a friend who acted as a lookout for the night and only baseball caps to hide their identities.

“I made a really basic stencil one night after midnight in one of the art studios and got all my supplies. A friend of mine accompanied me as my sort of lookout, and I mean we didn’t even dress up, because we wanted to look as inconspicuous as possible. We put on baseball caps to look a little disguised, we didn’t want to look like we were purposefully dressed in all black to look stealthy,” Conway said. “We went out at 11:30 on a weeknight on campus, maybe a little later, and I would just stencil down and complete the tag really quickly with a can of spray paint. We spent three hours that night spraying the stencils all over campus.”

Conway said the members of the Trinity community noticed the tags overnight. The tags were mysterious, exciting and illegal; and Conway’s involvement stayed completely anonymous during his entire time at Trinity.

Responses varied among students, professors and administrators. Christine Drennon, head of the department of urban studies, said she stopped the first time she saw the tag on the outside of Storch Memorial Building.

“It’s such a great statement. Those guerilla tactics challenge everything if they’re smart, like that one was,” Drennon said.

“˜You Belong Here’ showed up on sidewalks, parking spaces and several buildings throughout campus. Although many were removed by university officials and others have faded over time, a few tags have remained. Conway said he would not be surprised if current students find the tags in strange places.

“They were meant to be in places where they would be happened upon surprisingly,” Conway said. “I wanted it to be intimate and surprising. I didn’t put them in areas that were already super activated or where people would be congregating in large groups. A lot were in parking lots, alcoves and underutilized spaces. I focused a lot on upper campus.”

And Conway was right. Rising senior Emma Lichtenberg first saw the tag during her sophomore year””the same year Conway was a senior.

“It was close to nighttime, and I looked at it and thought, this is kinda creepy,” Lichtenberg said. “I can appreciate the sentiment of belonging at Trinity, and I definitely do feel like I belong. But just the block letters below my feet made me feel like it was a little weird.”

Administrators took notice of the tags as well. Dean of students, David Tuttle, wrote a post about the tags for his blog “˜The Dean’s List’ in March of 2013, four months after the first tag went up.

“Of course I have to be against random stenciling on parking spots as it is definitely a violation of our stenciling policy, which I feel duty-bound to uphold. I want to be clear, in no way am I endorsing stenciling on parking lots at Trinity. This isn’t graffiti, because I understand it,” Tuttle wrote in the blog post.

Tuttle said that sometimes finding a place on campus can be difficult, but in times of doubt, fear and failure, students should embrace three words: You Belong Here.

“Whether it is prospective students, current students or alumni, hopefully everyone here finds a sense of place and belonging. It’s simple: You belong here,” Tuttle wrote.

The tags were not Conway’s first piece of campus development. During his first year, Conway assisted urban studies seniors to bring the white Adirondack chairs to prominent spots on campus. The initiative focused on encouraging students to congregate for work, admire the beauty and take full ownership of campus.

Conway said when he was at Trinity he felt there was a barrier to students feeling ownership of the place they called home, especially on upper campus where most academic buildings are found. The goals of the Adirondack project mirrored those undertaken in his You Belong Here piece. Conway said he aimed to encourage the reclamations of space on campus where he felt power was focused in the hands of regulators and administrators.

“You belong in this physical space to be doing whatever the hell you want to do. Reading a book, hanging out smoking a cigarette, or making out with your girlfriend or having a damn existential debate. That’s what the liberal arts college is about. I didn’t see that happening at Trinity,” Conway said.

Lichtenberg said she interpreted the tag as a call for inclusion.

“I belong right here in this spot. You chose Trinity for a reason and you’re here,” Lichtenberg said.

Drennon agreed.

“It gives you this anchor of place,” Drennon said. “A little smile on my face and a consideration of this being ours.”

Although Conway’s original intent for the piece was not focused on blanket inclusion, he embraces other interpretations and uses of the slogan.

“You have to accept that you have given up control of where that slogan’s gonna go. It was an ongoing experiment and it was going to be reinterpreted by every single viewer,” Conway said. “I think it’s great they’ve adopted a theme of inclusivity.”

Most of Conway’s tags have faded away from the surfaces they covered, and years later they have been brought back to light in our community. The survival of an original tag that he sprayed during that November stands as a reminder: You Belong Here.