Raising a child can be a second, third or sometimes even fourth job for their parents. Faculty and staff on campus give their all to their kids on campus, and then must return home to take care of their own children. As the cost of childcare continues increasing, parents are faced with the prospect of leaving that job to take care of their new reality: parenting.

Trinity serves under the jurisdiction of the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). As an institute of higher education, Trinity is required to hold the position of a faculty or staff member on parental leave for 12 weeks. During this time, whatever sick and or vacation days that have been accrued are spent up and the rest of the 12 weeks are unpaid.

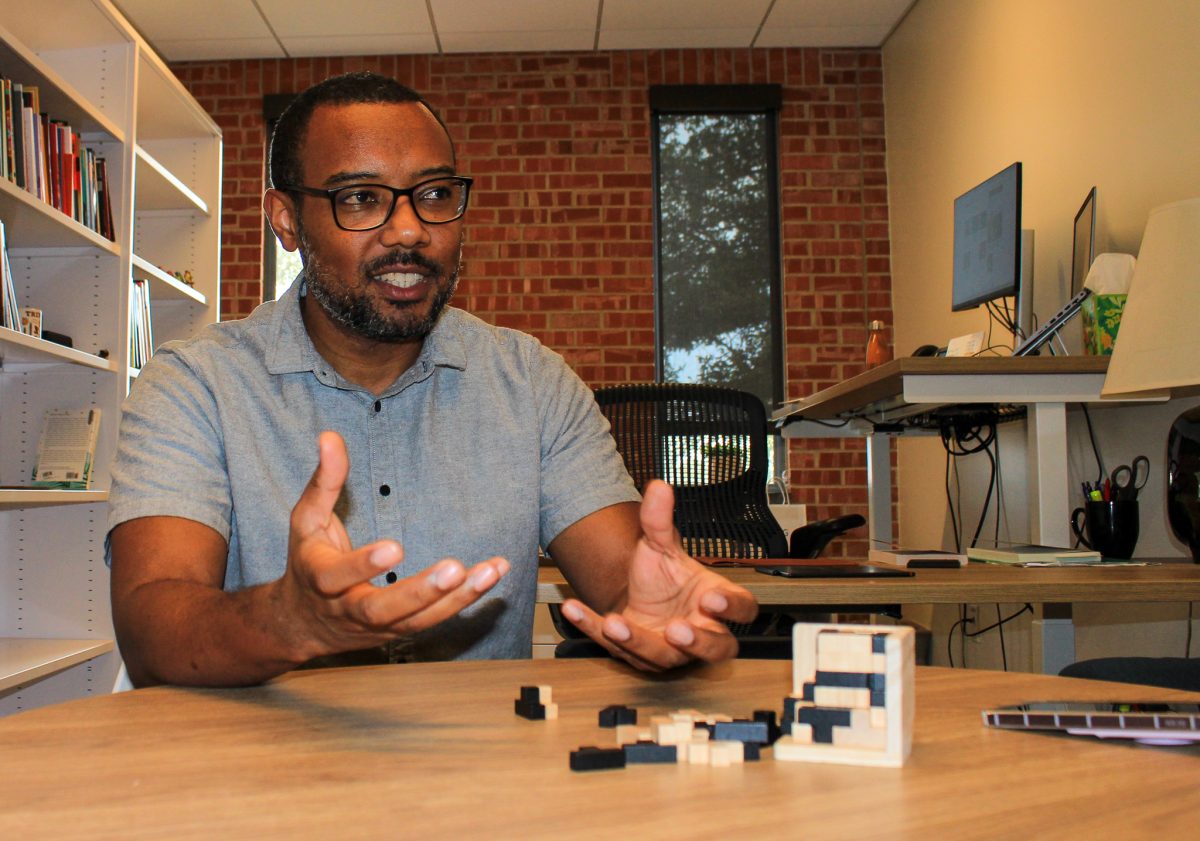

Another significant challenge of parenting is the stigma of gender associated with raising children. David Rando, professor in the English department, has a two-year-old son, and described some of the difficulties with parenting at that age.

“I think the biggest challenge is balancing all the elements of life: work, family, exercise, breathing and so on.” Rando said.

Rando received the rare privilege of an entire semester of leave once his son was born, which allowed him to spend as much quality time with him as possible.

“I’ll always be grateful to Trinity for that special time away from the responsibilities of work that allowed me to concentrate on our new family,” Rando said.

Other than providing daycare services on campus, Rando hopes for additional family relief to be provided.

“The family-leave policy for faculty and staff members should be standardized so that other families are afforded similar opportunities,” Rando said.

Jamie Thompson, director of Student Involvement, also has experience with being a mother, as both of her daughters were actually born while she was working as a member of Trinity’s staff.

As a mother, one of the struggles Thompson has battled with is being fully present in the moments she spends with her family.

“I only have a finite period of time with my daughters, so it’s in my best interest and theirs to turn all the things happening at work,” Thompson said.

Although parenting isn’t always the easiest job, Thompson raises her children fully aware of the spotlight placed on her because of her unique position.

“I know that there are male and female students that see me with my family on campus, in meetings, or on the weekends. I’m cognizant and try to be a role model so that people can see it’s possible to do this.” Thompson said.

In emergencies, Thompson must sometimes bring her children to a last-minute event. These unplanned excursions can oftentimes help Thompson insert a more human element into the work she does.

“At the GreekU retreat [last] weekend, my husband and two daughters came out on Saturday and camped. I either don’t get to see them for three days, or they get to join me out there for a period of time. That’s one way of balance; I bring them to me.” Thompson said.

Erin Hood, assistant director of Experiential Learning, anticipates change in her department because her first child is scheduled to arrive in a couple months.

“Everyone within the office has been extremely supportive, especially my supervisor, about my maternity planning. Overall, I feel a lot of institutional support from the people who work here,” Hood said.

One of Hood’s biggest concerns in the final few months leading up to her maternity leave has been allocating all of her work responsibilities and giving up paid leave days.

“Work is incredibly important too, we’re all here for a mission and a purpose, but it’s one of things that has to go by the wayside for about 12 weeks. For me it’s really about communication, knowing who the stakeholders are, and being in communication with them. I think it’s largely about expectation management and drafting plans,” Hood said.

Katie Ramirez, associate director of Career Service, takes a much harder stance on the privileges offered to mothers, as she has experienced the positive and negative effects of being a working mother already, as she has a toddler and is expecting her second child. According to Ramirez, there are almost no services offered to expecting parents other than an informal listserv, which is created and maintained by staff members and those provided through the institution’s contracted healthcare insurer, Aetna.

“H.R. is very supportive in providing guidance on how to navigate the technical aspects of leave (paperwork, etc.), but there is no guidance that would be provided once the child is born,” Ramirez said.

Because she already has experience as a parent, Ramirez has many suggestions for improving the parenting experience for faculty and staff, and one of her main concerns is one shared by many at Trinity: paid leave being provided to all staff members who are expecting.

“For many staff members, [the absence of paid leave] means either coming back to work before the 12 weeks of FMLA or accepting a portion of their leave unpaid, while also having to pay medical bills from the baby’s birth,” Ramirez said.

In order to receive payment for the whole 12 week period, a staff member would have to accumulate the entirety of the 160 hours of vacation time simultaneous with 320 hours of sick leave, which is composed of three straight years without illness. In an attempt to alleviate the extended unpaid period of the FMLA, Ramirez has also suggested extending the 160-hour restriction on saved vacation time. Another possibility suggested by Ramirez is allowing short-term disability insurance offered by the university to cover childbirth and a portion of income lost during maternity leave.

However, the needs and desires of new parents do not end after the 12 weeks of FMLA. In this respect, Ramirez also has several suggestions for Trinity that would alleviate the difficulties and fears associated with the first few months of working while caring for their newborn babies.

“A daycare partnership with hours that align with our work day … travel-related resources, such as for conferences or other regional events “¦ and [on-campus resources like] places to pump/nurse privately and changing tables,” Ramirez said.

By adding some of these suggested improvements to the university’s family leave policy would not only help fulfill a moral obligation to help give back to devoted members of the Trinity community, but also potentially serve as a constructive business maneuver.

The reality of the paid-leave predicament is that Trinity’s policy is in fact comparable to other domestic higher education institutions. As the university continues to innovate and improve, the policy protecting expecting parents may likewise require further growth to become as productive and helpful as possible.