Saturday marks a holiday that over one billion people around the world will celebrate: Chinese New Year. Also known as the Spring Festival or Lunar New Year, this holiday will celebrate the start of spring with food, family and small, red envelopes filled with money.

Grace Cheng is a junior accounting major, a first-generation American and the president of Chinese Culture Club. She’s lived in the United States her entire life but was raised by Chinese parents.

“As a kid, it was something that differentiated me from all of my white friends. Something that I can relate to with my other Asian friends. It was just a part of the culture,” Cheng said.

The traditions of Chinese New Year differ from family to family, or country to country.

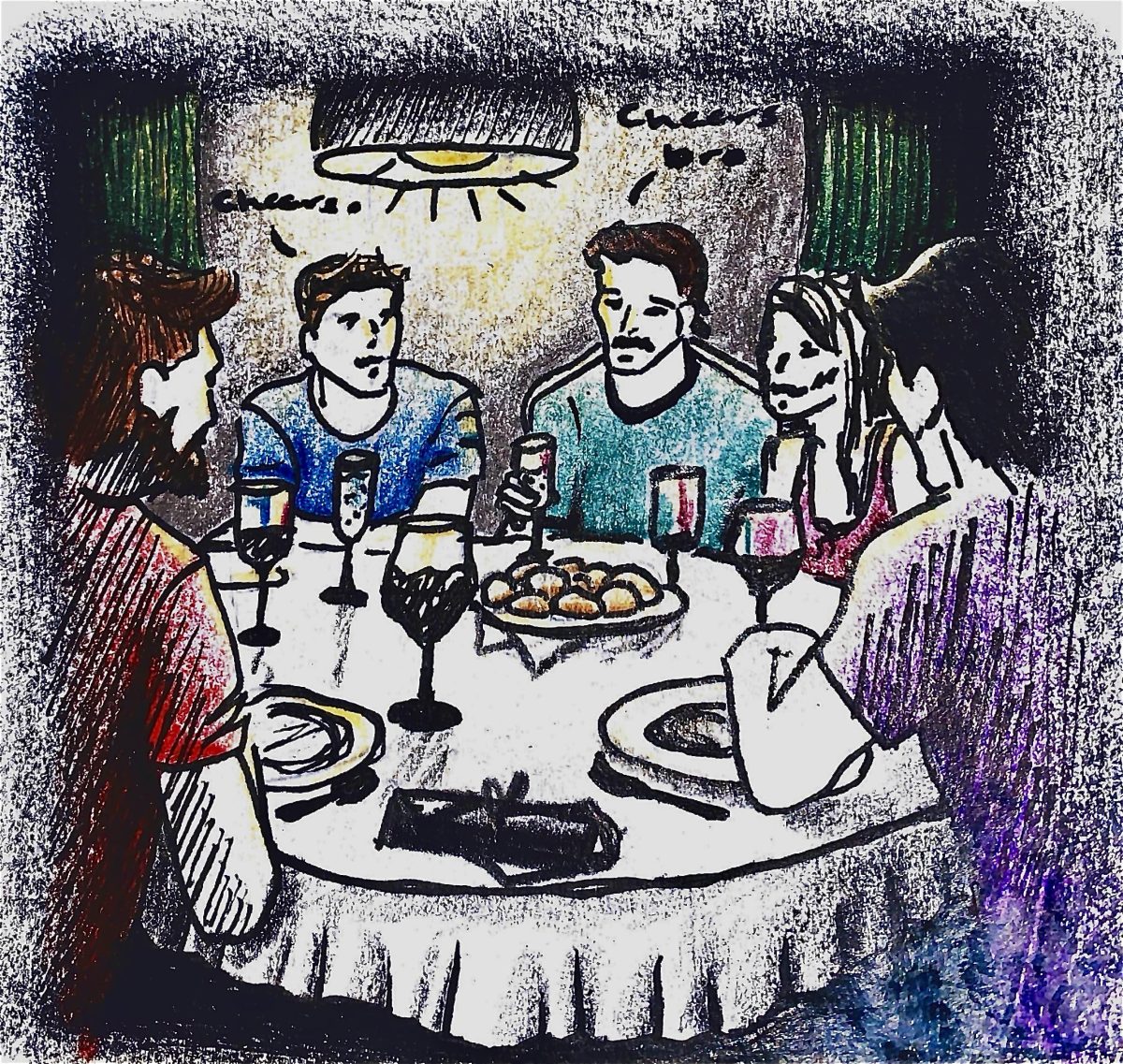

“I’m from the south of China and we don’t have such a strong tradition. Actually, it’s a festival where friends get together. My parents and some of their relatives talk about life. Plus many of them we only can see once a year, so this is the only chance we can be together,” said Dylan Yi, a first year from Guangzhou, China.

Yi, along with other international students from Chinese-speaking countries, will likely get together and try to emulate the celebrations that their families have at home. Because the international students are from different areas, their traditions may conflict with each other.

“We used to put things in the dumplings, like a good charm. It used to be coins, but it was really dangerous, so we replaced it with something edible. There was one day before New Year’s where we would just go shopping. We shop for all the posters with the Chinese characters on them,” said Haley Yi, sophomore.

Professors in the department of modern languages have also considered the rituals and traditions associated with the festival.

“Since age is counted from a baby’s conception, traditionally a child is considered one year old at birth, and thus is two when the next New Year passes,” said Stephen Field, professor of Chinese.

Jie Zhang, also a professor of Chinese, has a more personal tie to the holiday because she grew up in China.

“When I was young, I think my favorite part was eating the food. My dad used to cook a lot of specialty food, like meatballs and steamed buns with special fillings inside,” Zhang said.

For both the Chinese professors and Chinese students, the celebration of the New Year is vital to their culture. Whether or not they have the external celebrations, the holiday will still be significant internally.

“I would say that it’s part of the Chinese identity. It’s very important to everybody, wherever they live. It’s a celebration of family and food, but also hope. Hope for something new,” Zhang said.