This academic year, there has been a notable improvement in the inclusion and representation of black excellence in speakers at Trinity. We’ve been moved by Nikki Giovanni, inspired by Michael Sam, entertained by W. Kamau Bell and urged to action by Marc Lamont Hill. As I prepared to attend and respond to Michele Norris, a woman whose voice was present throughout my childhood as a co-host of NPR’s “All Things Considered,” I planned to write for the community about a thought that has frequently come up in conversations with other students who seek to improve the racial climate at Trinity and beyond.

The thought is somewhat of a paradox: the students who attend the diverse lectures at Trinity tend to attend many of them and work to improve upon their own personal prejudices, while those who would arguably most benefit from engaging with the subject matter of race, implicit bias and civil rights do not tend to attend lectures on those topics. It’s a form of the preaching to the choir concern. In other words, those who probably most need to have their biases corrected and addressed don’t freely choose to place themselves in settings in which that would be facilitated. This is a problem.

I thought I would attend the lecture, make some observations and suggest solutions which would incentivize the attendance of those least likely to attend. Yet by the end of Michele Norris’ Race Card Project lecture, I knew writing that piece as a response would not only be tone-deaf to her message but in some ways antithetical to it.

Sponsored by Texas Public Radio’s Dare to Listen campaign, Norris began her Race Card Lecture with an acknowledgment of the importance of listening. Norris embodied the work of listening by starting the night off opening the floor to the audience, as the crowd was asked to yell out what comes to mind when we think of the word “post-racial.” She heard each reply and repeated it without judgment. She modeled good listening which invited the audience to listen intently to her in return. With this invitation extended, I set aside my ideas about attendance and listened to her lecture for the sake of listening, not trying to only hear what was useful to the opinions I entered the room with. What I took away from that approach was a hefty dose of self-reflection and a reality check on my own disposition and approach to race in America.

One of Norris’ most powerful insights through her own research and involvement with The Race Card Project was the realization that in addition to being shaped by what we talk about in public and in private, we are also profoundly shaped by silences “” the things we don’t talk about. She spoke of “the weight of silence,” which she experienced in her family as well as observed other people’s stories about race. This all prompted me to begin reflecting on silence in my life, my reaction to the word “post-racial” and what my Race Card six-word story would be.

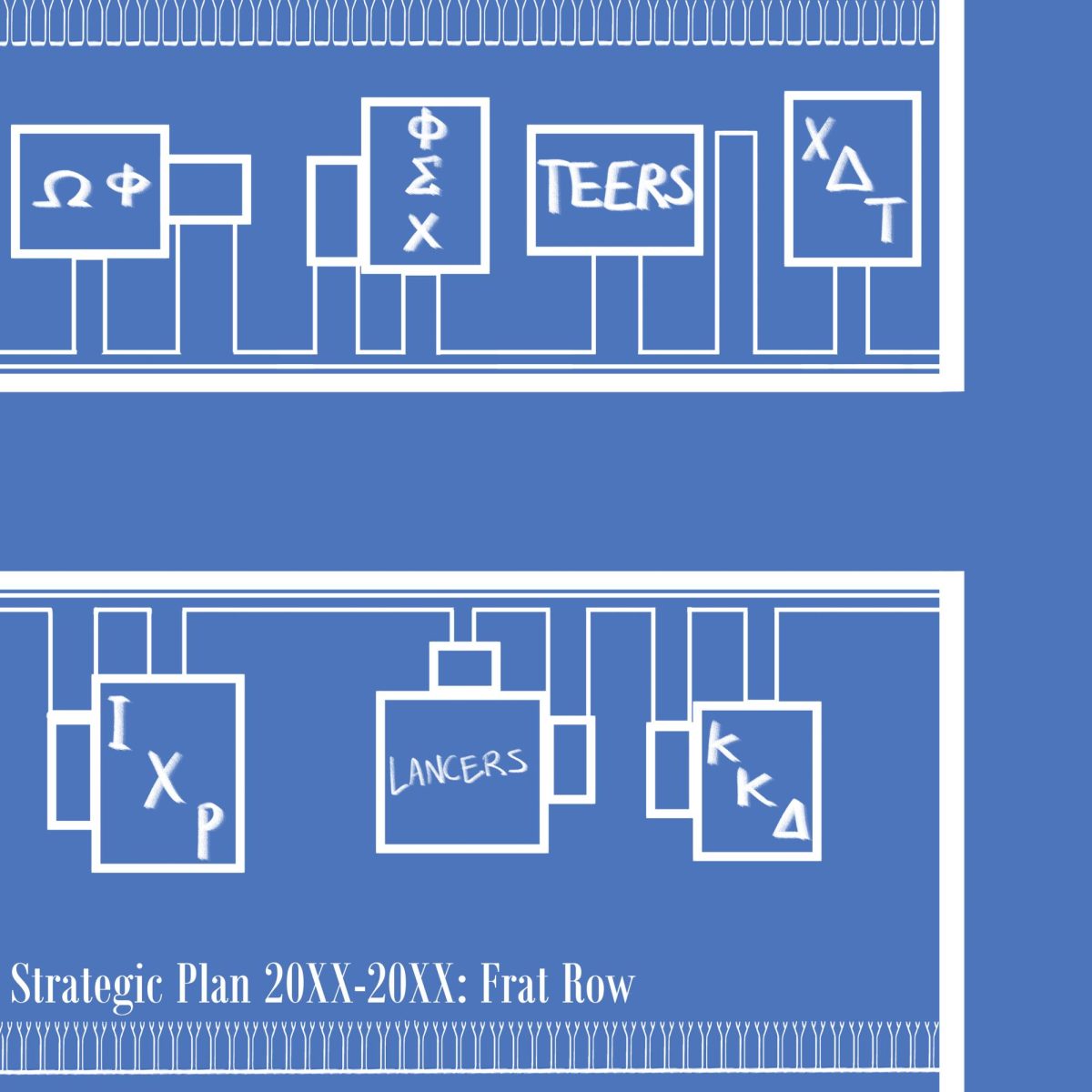

Norris wrapped up the evening with a more gentle call to action than I’ve heard before: an ode to the power of the individual. She acknowledged that it can be overwhelming to think of the millions of Americans who voted for Trump, or the millions of people who choose to be silent in the face of injustice. Instead of succumbing to this feeling of defeat and insurmountable opposition, she encouraged the audience to focus on what each of us as individuals can do. We can’t perhaps change the minds or undo the actions of millions, but we can be the one person in the room who stands up for what is just, who starts uncomfortable but important conversations with those we can touch. To me this also meant getting off my high horse from where I had planned to sit and criticize the reams of students who don’t attend diversity events on campus, and with my boots in the mud look at myself and contemplate what individual actions I can take to better listen and share stories to break the silence.

Norris said she made a habit of taking “left-turns,” changing direction and going on a path she hadn’t before imagined for herself. So here’s my left turn into less self-congratulatory territory, starting with my six-word story for the Race Card Project: white women need to do more.

To me, post-racial brought to mind the word “myth.” I had grown accustomed to rhetoric I was immersed in, only using the word when we talk about “the myth of post-racial America,” the ways in which it is imagined and not yet realized. Yet until Nov. 8, I did not have the slightest inkling of how I myself had fell for a strain of that myth through overestimating the influence of intersectionality on white women. Let me explain.

I thought I knew that America was not yet post-racial. I knew that racism was still prevalent both interpersonally, systemically and structurally in our society. But I unfortunately bought into a form of self-exculpatory white feminism that attributed the persistence of racism to white supremacy and patriarchy in tandem, genuinely believing that the responsibility for the unfortunate perseverance of those systems of oppression lay with not necessarily white people as a whole but more specifically white men as a social class. White women like me surely understood the importance of working collectively towards the goal of liberation from the hierarchies of sex and race that prevent people of color and all women from equality of opportunity, right? This delusion was shattered for me upon further examining exit polls in November of last year. CNN: 52 percent of white women who voted did so for Trump. Washington Post: 61 percent of white women with no college degree voted for Trump, 44 percent of white women with a college degree did too. I was shocked.

Where were the women like me who I thought would turn up to the voting booths and do their part to push for progress? As it turned out, my idea of my place in our nation’s dynamic was wrong. I was wrong. I thought I knew post-racial America was a myth, but in viewing civil rights for people of color as having substantial common ground with civil rights for women as a class and assuming other white women would do the same, I had generated my own mythical reality.

In part, I was able to dupe myself into this through the silence Norris brought my attention to. At Thanksgiving, I am asked to hold my tongue on issues of race and I oblige. I don’t bring up my concerns about racism to my grandmother because I’m not supposed to stress her out or cause conflict within my family. I don’t ask her about living through desegregation because it’s not considered polite dinner conversation. But that silence comes with a weight and a price.

Maybe some of us millennial white women still don’t believe it was “us” who elected Trump. The New York Times exit polling data says only 37 percent of voters aged 18 to 29 voted for Trump “” maybe this does cheer some of us up about the prospect of progress down the line. But to me it also says this again: white women need to do more.

I say this especially now for white women in that youngest voting age bracket. We stand a chance of changing the way the older white women we interact with see the world and race within it. We can no longer add passively in the weight of silence on race in private spaces as that weight has formed an anchor which keeps the best and the brightest people in America down at the bottom, where their rights can be carefully and quietly legislated away. Michele Norris moved me to a place of self-reflection and evaluation, where I can take this realization of my own misinformed beliefs and put myself to the work of having uncomfortable but essential conversations about race with the white women in my life I stand a chance of being heard by. We are tasked with practicing deep listening and speaking our truths to aid in understanding our differences. We are to fight for the America we want to see even if we don’t see it evidenced in front of us.