Approximately 40 students filled the Woodlawn Room in the Coates University Center on Tuesday to hear students and staff from Trinity Diversity Connection (TDC) and The Men’s Project broach the subject of toxic masculinity. The event, called “Can Straight Men Eat Ice Cream?”, is part of TDC’s ongoing Diversity Dialogues. Kezia Nyarko, sophomore and TDC’s public relations chair, came up with the topic.

“I was reading an article about Richard Hammond, who is one of the hosts on Top Gear. Someone mentioned ice cream, and he said, ‘Oh! I mean, I’m straight, so I don’t eat ice cream’,” Nyarko said.

Richard Hammond’s refusal to eat ice cream is one example of the social issue the event focused on: toxic masculinity.

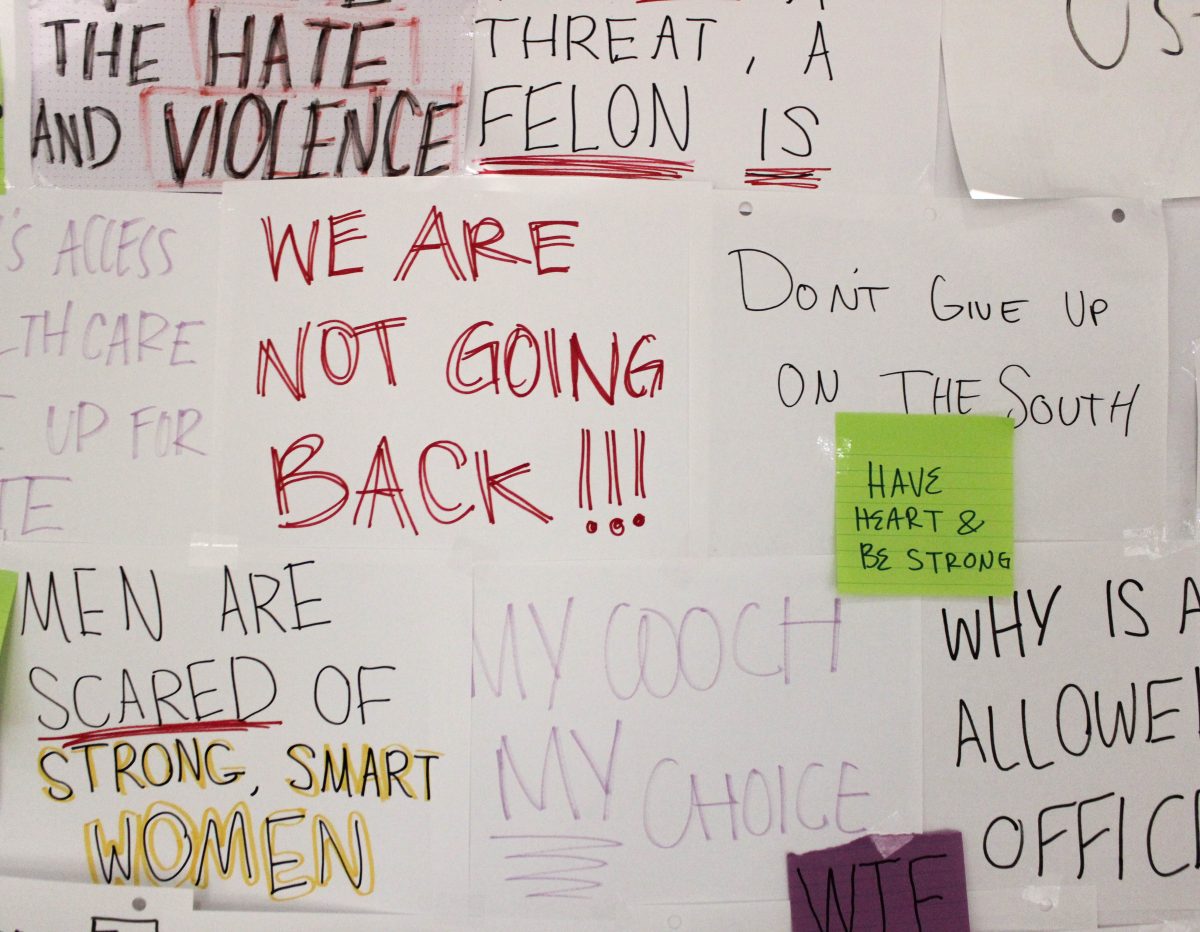

“Thinking about it, it’s hard to come up with just one defining experience,” said Nathan Tuttle, residential life coordinator. “Toxic masculinity really feels more like a set of rules and boundaries and limitations that people use to police you to make sure that you’re sufficiently masculine and that you’re living up to society’s expectations about what it means to be a man.”

Unhealthy thoughts and negative behaviors that stem from societal expectations placed on men fall under toxic masculinity.

“For example, masculinity tends to be more aggressive and assertive, so people might translate that into other behaviors,” said Samsara Davalos Reyes, junior and TDC president. “Rape culture and other things that aren’t supposed to be normal become normalized because masculinity is seen as something you have to perform.”

Toxic masculinity has a profound effect on college-age males, said Sheryl Tynes, vice president of student life and professor of sociology and anthropology.

“You see it at Trinity. You see it in who picks what majors, and that is partially pressure that young men feel,” Tynes said. “You see women in sociology, in education, in art, in English. We have more options; we have more choices than young men do. In some ways, young men are pigeonholed into this very narrow set of options in terms of what is acceptable and what sounds masculine. Majors themselves are gendered. They absolutely are.”

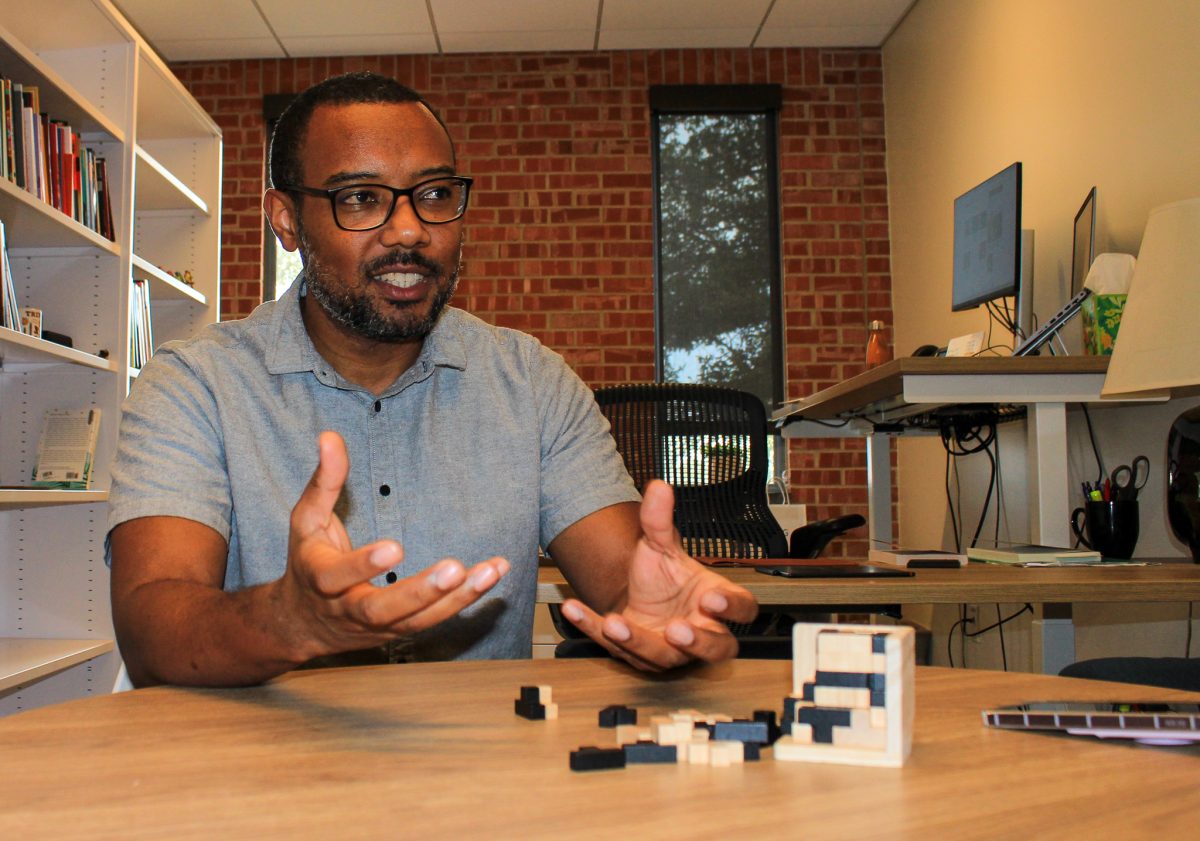

More effects of toxic masculinity can be seen in research conducted by The Men’s Project, which was introduced at the event by Tuttle and Jeremy Allen, assistant director for fraternity and sorority life and 2007 Trinity graduate.

“Some of my colleagues did some research on campus that showed that, overall, Trinity men didn’t have as high graduation rates, didn’t have as high GPAs, tended to get into some more trouble with conduct and were generally more disengaged than their female counterparts,” Tuttle said.

This poor performance by Trinity men is possibly due to the expectations placed on them.

“So people thought that guys were drinking more than they actually were in college. People thought that guys were skipping out on class more than they were,” Allen said. “People thought that they were hooking up with more people, more often, than they actually were. There was kind of this dissonance between expectations and reality, and that’s a really interesting thing that I think fits in this conversation about societal norms and masculinity.”

The expectations made evident in the research could explain the lower academic performance and worse overall behavior seen among Trinity’s male students when compared to Trinity’s female students. Expectations of poor performance may directly cause poor performance.

Effects of toxic masculinity on college-age males can be farther-reaching than unimpressive academic performance.

“Men generally take more risks than women,” Tynes said.

Men are also less likely than women to seek help when they have problems with mental and physical health. These trends are reflected in statistics handed out by Tynes. For every 100 women who die in the 15″“19 year old age range, 260 men die. For every 100 women that die in the 20″“24 year old age range, 294 men die. For every 100 women that die of suicide, homicide and accidents, 354, 459 and 285 men die, respectively.

The Men’s Project hopes to address some of these negative outcomes through peer mentoring and student-led group discussions.

“We’re looking to see if there are students interested to help us launch The Men’s Project, not from a data collection standpoint but from something like this: What if we met once a month and had a dialogue about what it means to be a male? About what it means to be a male on college campuses? What that means when you’re 18 years old, 25 years old, 30 years old?” Allen said.

Tuttle offered

“The idea of the program is that you have these near-peer educators, who are junior and senior men at Trinity, who are helping first-year and maybe sophomore men. To sort of guide and lead these small group discussions about what it means to be a man, around different topics: drinking, academics, health and fitness,” Tuttle said.

There are currently no future events planned by Men’s Project.

“We’re open to collaborating with anyone who’s interested in the topic. We’re looking for men who’d be interested in helping us facilitate these conversations, which we’re hoping will happen on a monthly basis,” Tuttle said.