Before 1980, Trinity was known for its tennis team, not its academic programs, like it is today. The future for Trinity looked bleak. Enrollment for many programs was down, and the university was struggling to keep up with the financial needs of struggling programs.

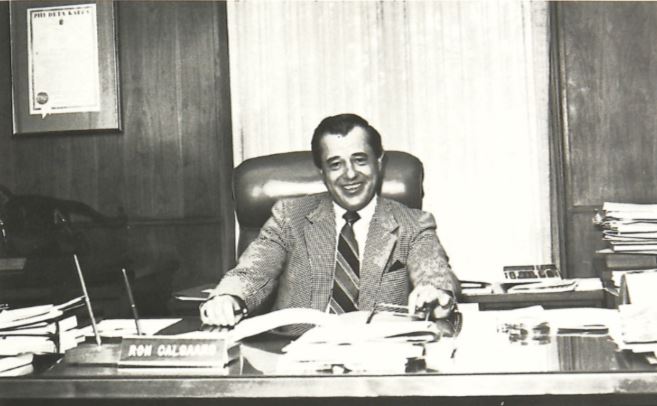

Then, about 35 years ago, Trinity did some rebranding. Ron Calgaard, former Trinity president, changed the university’s unpromising trajectory by eliminating several majors and programs.

Today, we make a tribute not only to those majors and graduate programs that did not meet Trinity’s standards in the 1980s, but also to other majors Trinity has lost throughout the years.

HOME ECONOMICS

Trinity’s home economics major began in 1917 and was discontinued in 1982. The major was primarily offered to women. Students in this major were required to take common curriculum classes, but they focused on “cookery,” “household administration,” “dietetics,” “sewing” and “dressmaking.” There was even a home economics cottage on campus in which students would practice cooking and running households.

“It reflects a kind of unfortunate history of things in that it was largely for women,” said Charles White, former Trinity vice presidewnt and current psychology professor. “Home economics was like, how to cook, how to clean your house, how to raise children; it had little to do with economics. It was more about home operations that fell to women.”

GERONTOLOGY

White joined the university’s faculty in 1979, when he was hired to be the director of gerontology — the study of aging. Trinity offered a graduate program that allowed students to focus on this area, blending psychology and sociology classes. The major was discontinued in 1985.

“Students would go on to sort of run senior centers, they would work for nursing home chains. They might be in health care administration somewhere,” White said.

JOURNALISM

The department of journalism was created in 1926, but changed to the communication department in 1985. At its establishment, the communication department offered classes focusing on article writing, advertising theory and practice, as well as church publicity. The department has since evolved to encompass the growing nature of journalism and media.

Sammye Johnson, who was a professor for the department of journalism and now works in the communication department, experienced the shift.

“We modified the existing curriculum in 1985 to streamline it and make it more responsive to an evolving media landscape with merging formats and myriad technological options,” Johnson said. “The field of journalism started changing, and it made sense for our name to become the department of communication to reflect vertical and horizontal shifts in the field.”

SECRETARIAL STUDIES

Secretarial studies began in 1938, within the English department, and ended in 1964. The program focused on preparing students for receptionist jobs. The major was completed in one year or the courses could be used to complete other degrees.

“In order to enable young men and women to prepare for a business position in a short time, the following curriculum, which may be completed in one year, is offered for high school graduates,” states the 1950 courses of study bulletin.

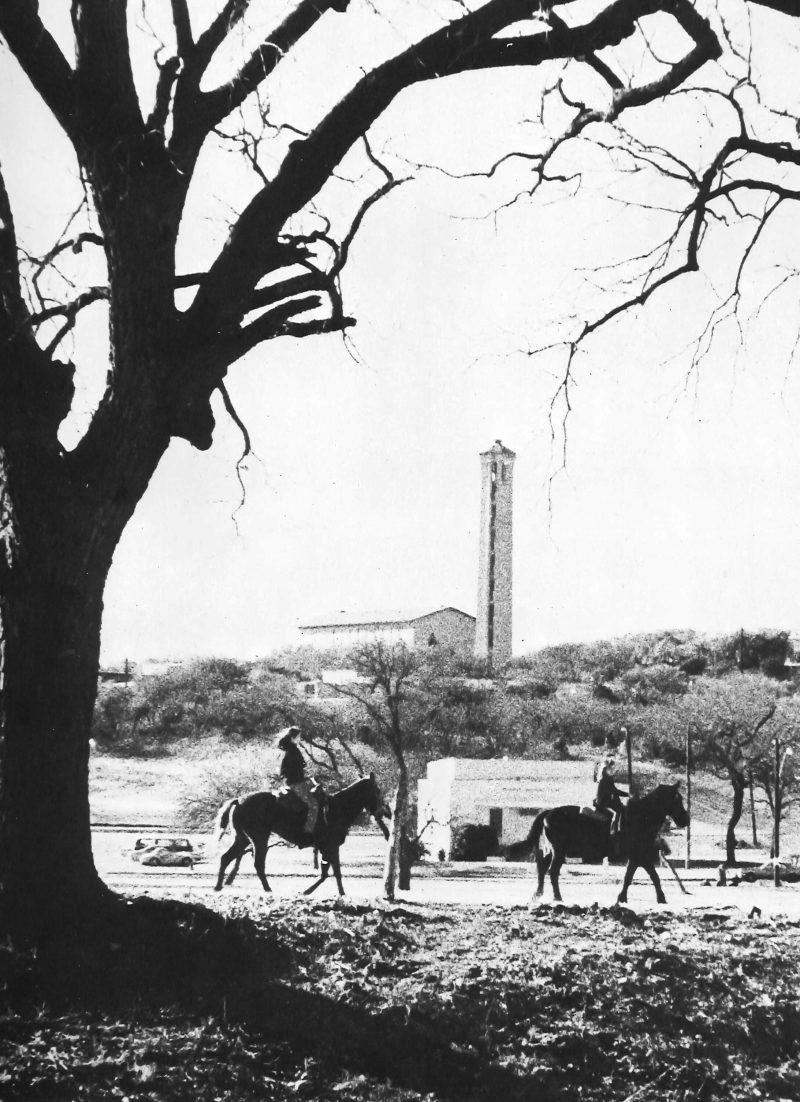

MILITARY STUDIES

In 1942, Trinity announced that the university would support the national war effort. To do this, the university created an accelerated track, by means of an enlarged summer program, for students who were interested in joining the military service. The program ended in 1945, but Trinity continued efforts to enable students returning from World War II to adjust to the university.

“Trinity is an approved school for young men preparing to train as officers in various branches of the military service,” states the 1942 courses of study bulletin. “A special Trinity University unit of the Texas Defense Guard gives excellent introductory training and service.”

HOME BUILDING

Trinity’s home building major was the first of its kind in the country, beginning in 1953. The major was designed to teach students how to construct homes, and produced a number of graduates who went on to start home building companies in San Antonio.

Brian Mayo, of Mayo Construction Company in San Antonio, graduated with this degree. Students even worked on the Charlotte Mayfield Home Economics Cottage at times. The home building major was discontinued in 1983.

“It was a very popular major for quite some time. They had to take courses in common curriculum and a lot of it was hands-on,” said Robert Douglas Brackenridge, former religion professor and Trinity historian. “It wasn’t like straight engineering. It was more of a practical course.”

GRADUATE PROGRAM

The biggest change Calgaard made was to discontinue the majority of the graduate programs Trinity offered. At the time, around 1980, Trinity offered about a dozen graduate programs. The programs were structured so undergraduate and graduate students could be in the same class, but graduate students were expected to meet higher standards.

Because of this, there was a doubt that graduate programs were performing at the standard of programs across the nation.

“There were some issues with the quality of the programs — were they really graduate programs?” White said.

Trinity was also having a difficult time finding students for the programs.

“Trinity was expensive enough that people, when they were looking for master’s degrees, could find public options that were cheaper. So, enrollment was an issue,” White said.

White saw the changes that Calgaard made firsthand, and is satisfied with the direction in which they pushed the university.

“He really moved us in a way that people began to recognize that Trinity was doing something in Texas,” White said.

WHO DECIDES THE MAJORS?

Currently, the process of adding, dropping or rearranging majors and programs now begins with faculty input. Faculty members can bring proposals to the University Curriculum Council (UCC) requesting changes in their departments.

“Faculty members bring those issues through the UCC, the UCC votes on those, they come forward to the entire faculty in the faculty assembly to vote on,” said Diane Saphire, associate vice president for institutional research and effectiveness.

These changes must then be verified by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, Trinity’s accreditor.