The Trinitonian has recently run a series of columns about the importance of civic engagement. From debating difficult issues with people with whom we disagree, to engaging with local politics, these pieces have stressed that college students have both the right and responsibility to make their voices clear in civic conversations.

I have little to add to these editorials besides expressing my esteem and agreement. But when I think of civic engagement among young people, I often find myself drawing upon that which I know: East Asian history. In the past one hundred years, students have been a central driving force behind the history of the region. With demonstration after demonstration, students have shown an immense power to incite change and, in many ways, define democracy.

The ways these students have defined democracy are often diverse and multi-faceted. For the students of Korea and China, who marched on March 1 and May 4 of 1919, respectively, democracy meant the dignity of national sovereignty and freedom from colonization by Japan. For the Japanese students who marched in May of 1960, or the Taiwanese students who broke into the headquarters of their legislative parliament in 2014, democracy meant the right to have a say in national policy and foreign relations.

For others, democracy was more quotidian: in the words of Wu’er Kaixi, a student leader of the 1989 Tian’anmen square movement in China, democracy meant, “Nike shoes. Lots of free time to take our girlfriends to a bar. The freedom to discuss an issue with someone. And to get a little respect from society.”

But in many student demonstrations in East Asia, their demands for democracy center on the right to vote. In South Korea, students overthrew their government to establish a new, albeit short-lived, republic in 1960, a central tenet of which was the right to vote in fair and competitive national elections. When only a year later that republic was replaced by a military dictatorship, students marched again, and again, and again until a fair election was held in 1988.

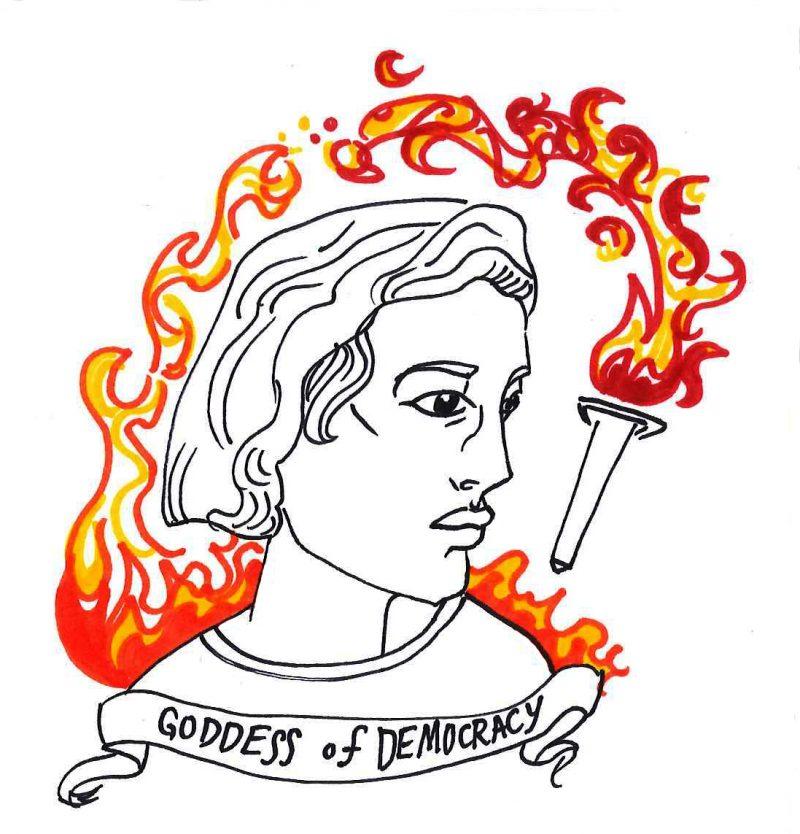

In Hong Kong in 2014, students occupied the central business district of the city to fight for the right to vote for their legislative representatives and chief executive. And in May of 1989, nearly one million Chinese citizens gathered at Tian’anmen, built a paper mache “Goddess of Democracy” modeled on the statue of liberty, and demanded that their government extend its modernization program to include popular elections for national government positions.

Not all of these movements immediately convinced their governments to concede on specific demands. Many of them ended with violent crackdowns. Hundreds died in the May 18 democratic uprising of 1980 in South Korea, which began with students from Chonnam university marching for democratization. Thousands of unarmed students died at Tian’anmen. More recently, the three student leaders of the 2014 Hong Kong student movement were sent to prison for their role in the protests.

Every time I teach about student protests, I find myself awed by the sacrifices these students made for something that I have never had to fight for — nor is it lost on me, as an American woman, that others have had to fight for my right to vote in this very same time period. I am also consistently struck by their fortitude.

In a conversation with Alex Lo, one of the organizers of the 2014 Hong Kong student movements who recently faced jail time, he expressed to me that the end of the student movement and the threats of incarceration did not leave him discouraged. When he saw young people in Hong Kong continuing to organize, fight for representation, and get involved in the community, he felt hope. I do too.

Ultimately, these historical moments show that the future is contingent and indeterminate, and that human agency matters. We do not know if this next election, this next protest, or even this next conversation with a friend, family member or classmate will change our futures.

But history teaches us that the only drivers of change are people themselves. So get involved, have conversations, become engaged. And in the name of all those students who fought for elections in their countries, vote.