Students may have noticed that certain classes and departments have adopted four-credit-hour courses in recent years. This is a symptom of a quiet conflict that has persisted among faculty since 2013, a debate over how the university should translate course loads into credit hours.

The 2009–2010 Course of Study Bulletin defines a semester hour as “one 50-minute period of recitation or lecture, or three such periods of laboratory work, each week for a semester of 15 weeks.”

This definition recommends two hours of out-of-class preparation. On Oct. 25, 2013, the Faculty Assembly voted to change this definition, which decoupled the link between the credit hour and time spent in the classroom, called “contact hours.”

“The equating of credit hours and class contact hours was never official Trinity University policy,” said Glenn Kroeger, professor of geosciences and member of the University Curriculum Council (UCC.) “In fact, what triggered the current policy and the debate that occurred during its adoption was that … this policy was deemed inadequate.”

This change was divisive among professors. Some believed it wasn’t representative of the work done out of the classroom; others cited pedagogy as a reason to extend the credit hour.

Aaron Delwiche, professor of communication and member of the UCC, recalled the division the situation created.

“Trinity faculty, we all respect each other. We all get along, but this is the most divisive issue I’ve seen,” Delwiche said.

Delwiche doesn’t agree with the coupling, explaining that time with professors is important for students.

“I firmly believe that we should keep them coupled, the contact hour and the credit hour,” Delwiche said. “I think that what you’re paying for at a place like Trinity is the time to interact with Trinity. We have this great faculty-to-student ratio; it’s one of the lowest in the country.”

According to Mark Lewis, professor of computer science, the change of definition didn’t clarify how credit hours determined by work would be measured.

“The general rule across campus was that, if a class was scheduled for three hours, it got three credits. And at least that wasn’t arbitrary. It was defined,” Lewis said. “Now the definition is that how much credit you get has nothing to do at all with any class, with how many hours you meet a week. It’s only supposed to be how many hours of work you spend on it — which would be fine, if we had any way of reinforcing it.”

Lewis explained that if the definition allows credit hours to be based on the work required for a class, classes worth more credits should give more work than those worth fewer credits.

However, this contradicts the experiences Lewis has had with students.

“I hear students telling me that their four-credit class is less work than a one-credit class,” Lewis said. “What I hear from students is that there are a number of these four-credit classes that are not pushing students to think deeper. They’re just getting more credit.”

One might think the change unfairly allows students to get more credit for different, perhaps less-involved work. Kroeger disagrees.

“The question is, ‘What’s important for the course you’re taking?’ If the course is about reading British novels, then reading British novels is far more important than sitting in class and listening to somebody yap at you about British novel,” Kroeger said. “My view is that ought to be left to the person in the department. I don’t know how to teach British novels, but I assume that my colleagues who specialize in them do, and I want them to choose how they portion [the] course load to teach what they want to teach.”

Lewis worries that there is no way of enforcing how much work goes into a class or how much work is administered to a class.

“My fear was that this will become a joke, that the number of credit hours for a course become meaningless,” Lewis said. “And I think that’s where we’re going.”

Kroeger thinks the system is fair. Because the university doesn’t enforce a standard number of credit hours per course, professors are able to choose which works best for their departments, provided that the classes are approved by the UCC.

“The model that we ended up with does not require that coupling, but it doesn’t prohibit it, either,” Kroeger said.

Lewis agreed that the departmental flexibility is good.

“One of the things that’s kind of nice about this system is that we did not university-wide impose this upon everyone,” Lewis said. “There were schools that did that.”

Kroeger sees the advantages of both systems, but ultimately thinks the current system is better since it gives professors the option between course hours.

“I listen to both sides, and I understand the difference, but we all have to ultimately decide what we believe in,” Kroeger said. “I think that, generally, students need to spend more time doing fewer things better.”

The current definition of the credit hour is flexible.

“One of the key terms in the credit hour policy itself is ‘expected’ student academic work, and I think that helps with the measurement part of it,” said Duane Coltharp, associate vice president of academic affairs. “There is absolutely no way to measure how much work students actually do.”

According to Coltharp, departments have their own measures of how long it will take to do certain assignments, e.g. how long it will take to read or write a certain number of pages.

“We know that not every student reds every page that’s assigned,” Coltharp said. “When it comes to measuring how much of the student work we think is going to go into a course, that’s what departments have actually done. They’ve counted up how much reading goes into a course — how much writing it takes to go into a course, how long they think it will take to take an exam.”

Coltharp said that though this is just an approximation, it gives the university an idea of how much work goes into a class.

Delwiche remains skeptical. According to him, even if students are doing work outside of class, it’s time in class that is most important.

“I feel like moving to the four credit hour is kind of unfair to students because they’re paying for that extra credit hour, and yet they’re not spending that time in the classroom,” Delwiche said.

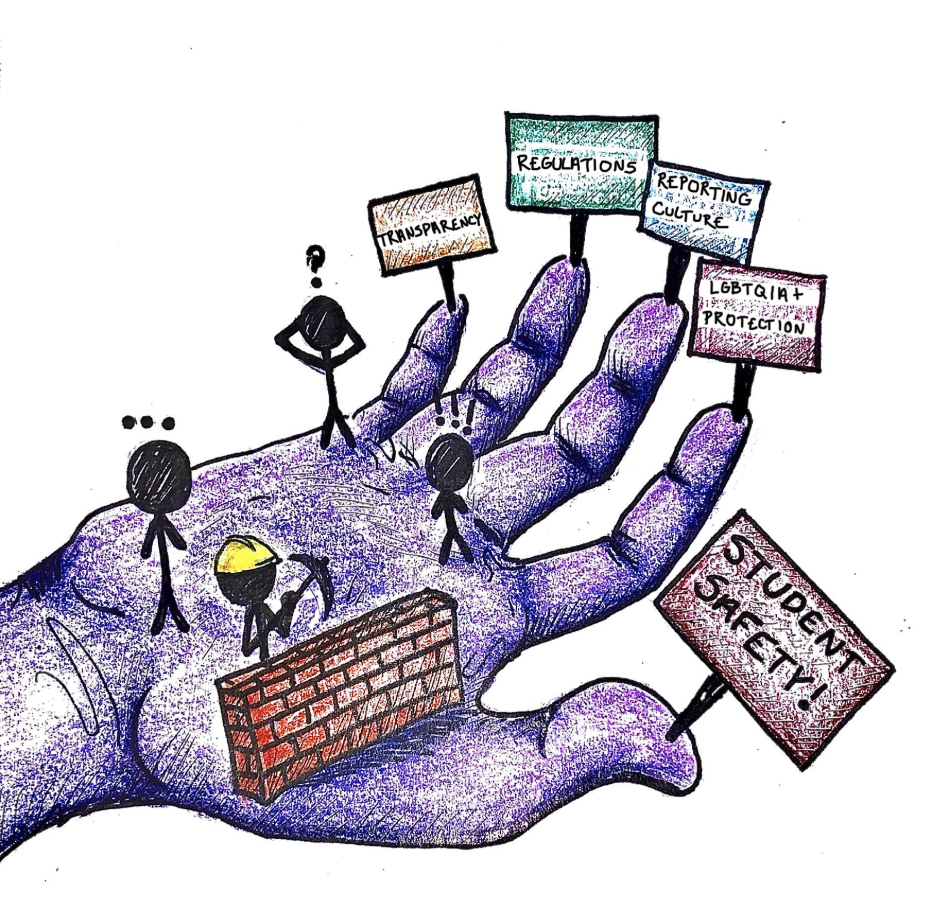

Trinity also updated its credit hour policy in order to maintain its accreditation.

“We have to have a credit hour policy, required by our accreditor because it’s required by the federal government,” said Diane Saphire, associate vice president for institutional research and effectiveness.

Saphire explained that any time the university looks at changing a policy, our accreditors, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACSCOC), require that the policy be documented and approved. In this case, the new policy was approved by the UCC, then sent to be approved by the Faculty Assembly, and the minutes were shared with SACSCOC to document the process.

According to Saphire, the UCC works hard to ensure courses worth four credits include that level of work outside of the classroom, too.

“The person making the proposal has to justify pretty specifically what extra work the student will have to do that will be the equivalent to the number of credit hours that they want to award for the course,” Saphire said. “When we show the work that the UCC does — that they don’t just rubber stamp these — and some of the ones that come through have this extensive justification.”