by Georgie Riggs, Arts and Entertainment Editor

I haven’t seen that many scary movies, but I have seen nine “Nightmare on Elm Streets” — including the Michael Bay-produced reboot. As someone who usually resorts to looking up a horror movie on Wikipedia to read the plot summary instead of seeing it in person, it’s odd that I can say I’ve actually seen a full scary movie franchise.

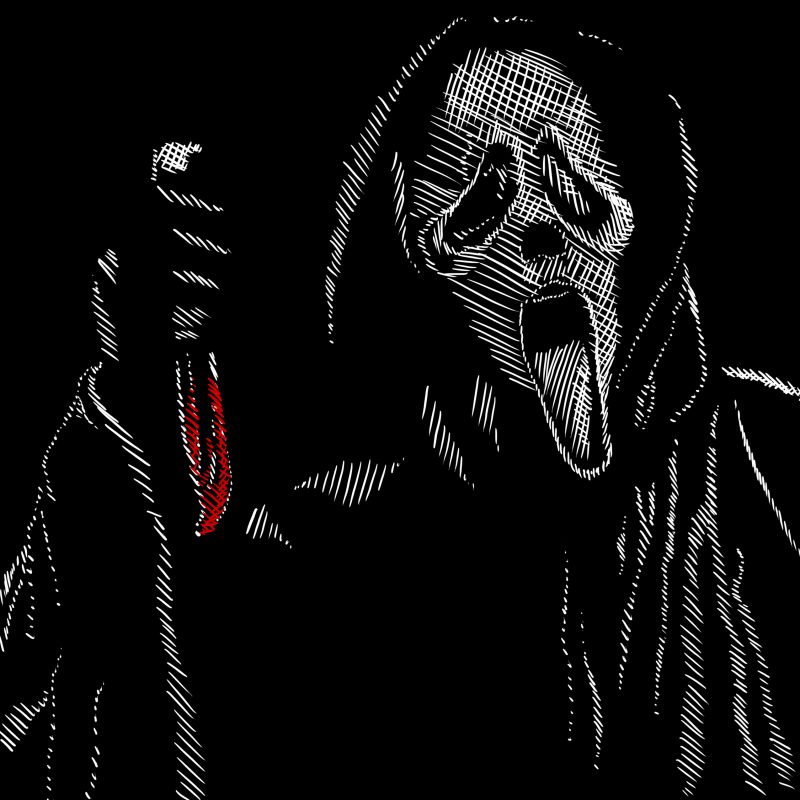

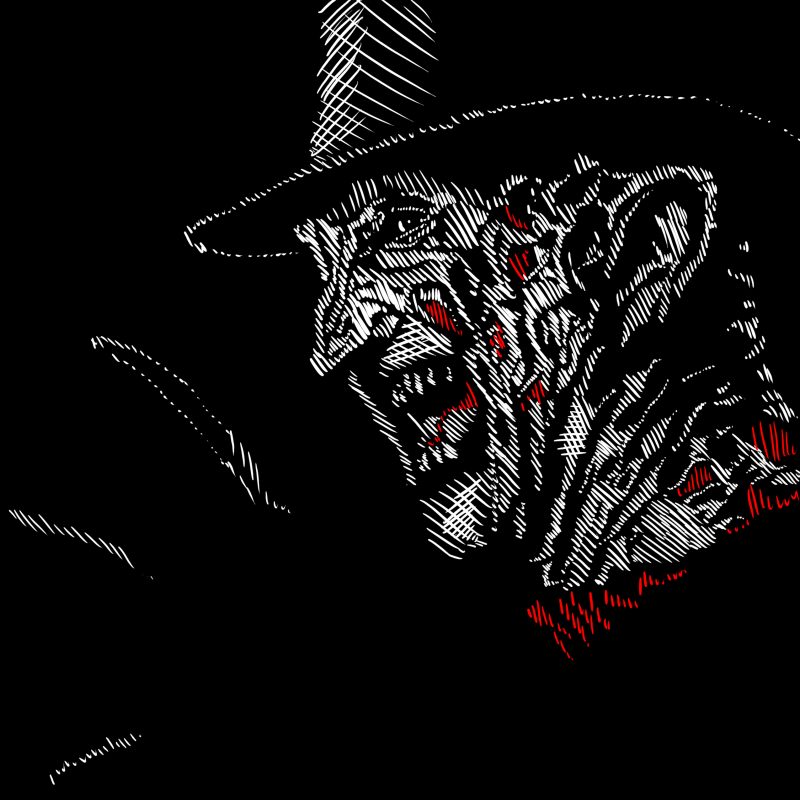

For the unenlightened — or unenfrightened? — “A Nightmare on Elm Street” features the killer Freddy Krueger who wears a striped sweater, only exists in dreams and murders his teenage victims only as they are sleeping — often in a boiler room dreamscape. Freddy is scary and mysterious — at least in the first film — like most slasher villains, but he also represents something more abstract and universal in his subconscious lurking.

Of course, “Halloween,” “Friday the 13th” and the majority of slasher films are also dealing with an abstract, universalized fear. They just place those fears into one anonymous, infallible man. “A Nightmare on Elm Street” does something different, presenting an entirely new and original way for horror movie franchises to ascribe fear to its villain.

The abstract is embraced rather than fully humanized in “Nightmare,” which negates comfort in knowing that if you just killed Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, you’ve killed the evil. Freddy Krueger, however, is more than just a burned man in a striped sweater: he represents the entire state of dreaming.

The dream conceit is best illustrated in its imagery and death setups. The best known scenes in “Nightmare” come from the first in the franchise, directed by Wes Craven, horror giant and “Scream” creator. Craven ignores reality entirely in crafting his excessively expressive death scenes. The first killing in the film drags a girl up a wall and onto the ceiling, leaving an impossibly large trail of blood in her path. Later, her corpse appears in an empty school hallway, wrapped in plastic; this leads Nancy — the first film’s final girl played by Heather Lagenkamp — into the boiler room with Freddy.

The dream setting leads to most murder taking place in the bed in equally surreal and weird ways. Nancy’s boyfriend is killed by Freddy within the mattress of his bed. Freddy drags him — along with his television set and his record player — into the bed, which results in gallons of blood erupting from the bed. The image recalls the elevator of blood sequence in “The Shining” in that it communicates more emotion than fear.

All of these images may sound excessively gory — and they are. But the dream setting means they are charged with a deeper meaning. If what happens in dreams is both real and unreal, the scariest thing about the world might just be how much of it is ruled by our own subconscious. It’s not just violence for the sake of violence but violence meant to build increasingly impossible images that lead to cathartically campy conclusions.

This cathartic camp is probably the best way to describe the rest of the franchise. Moments of truly original imagery are interspersed with scenes meant to be scary but are so bad that they are funny. Different directors for seven sequels means different styles and varying levels of quality, adding to the eclectic joys of watching the full franchise: you’re always going to get something new and unexpected.

One of the most common insults of slasher films is one that I am guilty of believing as well: they are all made of the same tropes featuring dumb teenagers and terrifying serial killers. The ‘90s and ‘00s were populated with clever horror movie satire seen in “Scream” and not-so-clever parody seen in “Scary Movie.” But “Nightmare” is just as aware of these tropes; it features smart teenage protagonists who spend the runtimes of the films trying to stay awake to figure out clever ways to escape an increasingly caricatured killer.

With “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” you get the experience of late ‘70s and early ‘80s slasher — reckless teen sex and synthy scores are aplenty — with the unexpected logic of dreams taking the images and plots into a bizarre world that’s part-horror and part-comedy. You can have your camp and eat it too — just as long as you chase it with a gallon of coffee and a handful of caffeine pills so you never fall asleep again.