University officials managing Trinity’s endowment are currently monitoring the upcoming federal tax on private university endowments. The endowment tax, which the U.S. Congress passed in late 2017 as part of the comprehensive Republican tax bill, would affect institutions with endowments valued at more than $500,000 per student.

“The law is not very specific, so the Treasury Department and the IRS have to determine the rules around [the endowment tax],” said Tess Coody-Anders, vice president of Strategic Communications and Marketing. “We’re waiting to hear what those rules are to see whether or not we will be affected going forward.”

Last December, Trinity hired former Texas congressman Henry Bonilla to lobby against the tax provision. Despite this effort, the provision passed and would tax 1.4 percent of endowment assets. Whether the law will apply to Trinity primarily depends on the definition of endowment assets. Currently, it remains unclear whether funds held in trusts by financial institutions fall under the definition of the taxed assets.

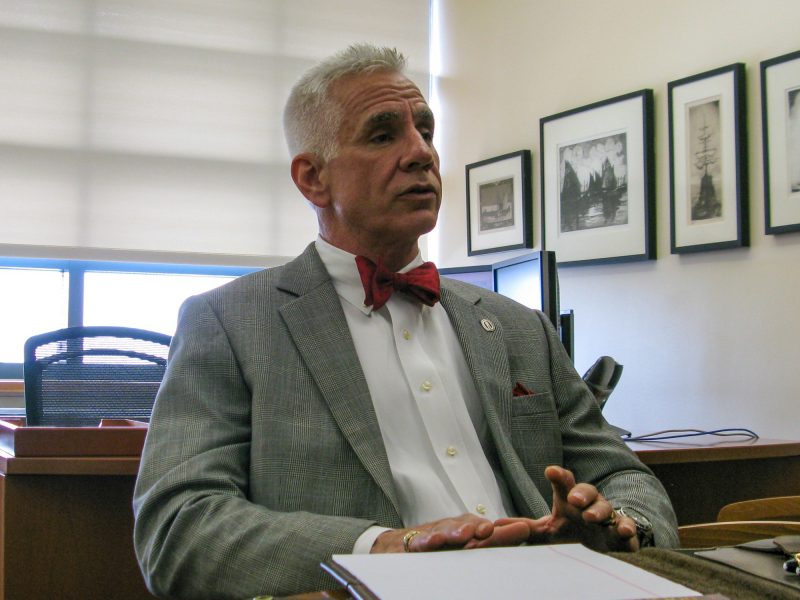

“There is some question of whether [trust] assets would be counted in this calculation of making us subject to the tax or not,” said Gary Logan, vice president for Finance and Administration. “This is really significant for Trinity because they make up about a third of our endowment. If those assets are not included in the calculation, Trinity’s not subject to the tax. If they are included, it’s questionable whether we are or not.”

In order to engage with policymakers during the application of the endowment tax, Trinity communicated with the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and the Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT), two advocacy organizations for educational institutions of which Trinity is a member. Of the 42 members of ICUT, Trinity is one of three institutions that may be affected by the tax, along with Rice University and the Baylor College of Medicine.

“One side of our strategy is, through legislative action, to encourage Congress to take up this issue and see if we can get the endowment tax removed through legislation,” said Ray Martinez, president of ICUT. “The other strategy would be to offer comments on the regulatory side that would have the IRS interpret this endowment tax provision in the least harmful way.”

How the tax is interpreted could have real consequences for students of private universities with large endowments, including Trinity students.

“Anything that causes revenues to be lower than they would have been otherwise affects students,” Logan said. “A significant portion of that revenue supports student financial aid.”

If Trinity were to be subject to the tax, Logan projected that Trinity would pay up to one million dollars per year, either out of the current operating budget or out of the endowment itself.

“We likely would take [the money] out of the endowment rather than take it out of the operating budget currently,” Logan said. “This means that all future revenue streams off the endowment are now hindered, so it would harm future generations of students, faculty or staff.”

Beyond the immediate financial effects of the tax, many fear that it sets a dangerous precedent about the perception of university endowments.

“The perception is that perhaps all private higher education does not do enough to address college affordability issues,” Martinez said. “The reality is very different. Usually the biggest source of financial aid is institutional grant aid. The belief from some on Capitol hill that we have to compel institutions to support students is a precedent that [ICUT] strongly opposes.”