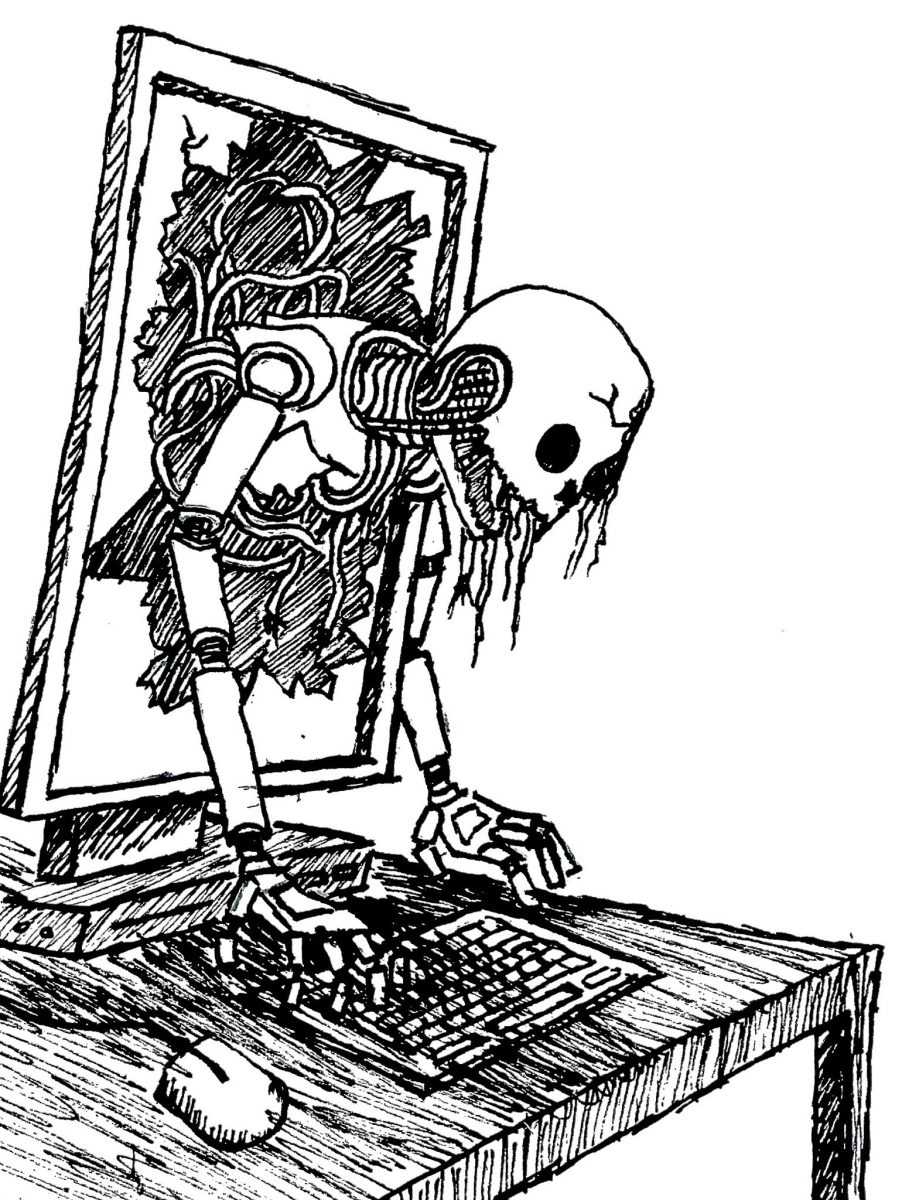

Illustration by Andrea Nebhut

Do we find serial killers sexy, and if so, is it related to The Notebook?

That’s a loaded question, but let me explain. High school musical star Zac Efron was recently cast in “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil,” a film about the life of notorious serial killer Ted Bundy, who sexually assaulted hundreds of women and murdered thirty. The trailer for the movie depicts Ted Bundy as a charming, seductive man (his real-life charm is in question), but what’s disturbing is that many teenage girls and women online confess being attracted to Ted Bundy, who, again, is an actual serial killer. While I don’t want to detract from the seriousness of Bundy’s real-life crimes, there was a similar controversy around the Lifetime-turned-Netflix series “You,” which features a protagonist, Joe, who becomes obsessed with a woman and gradually gains control over her life, killing her friends and other “bad influences” before eventually killing her. While the main actor, Penn Badgley, has reminded fans that Joe is written as an unlikeable villain and as a cautionary tale, many people still sympathize with the character and find him attractive. Have we taught women from a young age that stalking and abusive tactics can be a sign of love?

Romantic comedies are associated with cheesy fun around Valentine’s Day, or just for when you’re bored and want an escape from reality. Many romantic comedies, however, involve sexist and harmful tropes. Let’s take consent, which should be the bare minimum for any healthy romantic or sexual relationship. But in a culture that already pressures women into accepting men’s advances, romantic comedies like “The Notebook,” where male love interest Noah hangs off a ferris wheel and threatens to let go if Allie won’t go on a date with him, normalize those unhealthy messages even more. A 2015 study by psychologist Judith Lippman found that when female college students watched romantic comedies featuring stalker behavior like “There’s Something About Mary” and “Management,” as opposed to horror movies, they were more likely to see it as romantic — especially if they perceived the movies as realistic.

However, consent and lack of it isn’t limited to extreme behaviors like stalking. For example, in Aja Romano’s Vox analysis of “A Star Is Born,” titled “A Star Is Born has a problem with consent,” she lists all of the subtle moments where Lady Gaga’s protagonist Ally has her “no” turned into “yes” by the male characters around her. The surprising thing is that the original “A Star Is Born” female lead was actively seeking out opportunities for her big break, while in the remake, Ally making her own choices over her creative career is treated as selling out by the plot, where her male co-star’s music is authentic. In movies like “The Devil Wears Prada,” women having a dedication to their career is treated as a character flaw in an era when prioritizing a career instead of starting a family is still stigmatized.

These types of messages in romance movies are specifically detrimental to people in the LGBT+ community — especially lesbian, bi and trans women. When romantic films with LGBTQ+ characters feature storylines about men pursuing and winning over lesbians (1997 romcom “Chasing Amy”), dubious consent or inappropriate age gaps (“Blue Is The Warmest Color,” “Call Me By Your Name”), this sends negative messages to young audiences as well as perpetuates homophobic and transphobic stereotypes. Women of color also receive uniquely harmful messages from romantic movies and TV shows. 2018’s “Where Hands Touch” (starring Amandla Stenberg) was widely criticized for its plot where a biracial Black girl falls in love with a Nazi, and Netflix’s “Siempre Bruja” (marketed as a Colombian “Sabrina the Teenage Witch” with time travel) came out last week and also features a disturbing “falling in love with your oppressor” narrative. Women of color and women who love women deserve better. We deserve to see ourselves represented in healthy and loving relationships on screen (and there are romcoms that are better with this, such as “To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before” and “Hearts Beat Loud”).

It’s okay to enjoy problematic media now and again — biased opinion: this is NOT true for “Love, Actually” — and I’m not claiming that fiction has a one-to-one relationship with reality or that audiences don’t have the ability to think critically. However, as Lippman’s study shows, fiction does affect reality (and vice-versa! Dialectics!) to some extent. No one exists in a vacuum (if you do, please write a Trinitonian column about it). Our thoughts and actions are influenced by the media we read and watch, among countless other variables. We have the power to create a better world where healthy, happy and consensual relationships are the norm, and part of that starts by writing them into our fiction.