Photo by Gabriella Garriga.

Correction: In the original version of this story, the Trinitonian mischaracterized Deneese Jones’s letter to Caroline Tran as an official statement released by the university. The Trinitonian accessed the letter through the Twitter thread Tran posted. Updated September 13, 2019.

In Fall 2018, then-junior Caroline Tran accused chemistry professor Adam Urbach of sexual harassment. Tran reported the case under the university anti-harassment policy, and an investigation followed. However, the investigation did not find Urbach in violation of the policy, prompting Tran to relay her story via Twitter.

Tran, a biochemistry and molecular biology major, was randomly assigned to work with Urbach as a teaching assistant in Fall 2017. In Spring 2018, Tran joined Urbach’s research team. At that point, Tran was uncomfortable with Urbach, alleging that he had made insinuating comments about his and her personal life.

“There were multiple instances where [Urbach] made me feel uncomfortable, and the situation was pretty much the same every time. He would say something that made me feel uncomfortable,” Tran said.

Tran’s Twitter thread, which was created through a friend’s account on June 27 of this year, has garnered 844 retweets and 557 likes at the time of publication. Tran’s disappointment with the result and process of the investigation led the Trinitonian to inquire about the process for reporting sexual harassment and assault under a variety of circumstances.

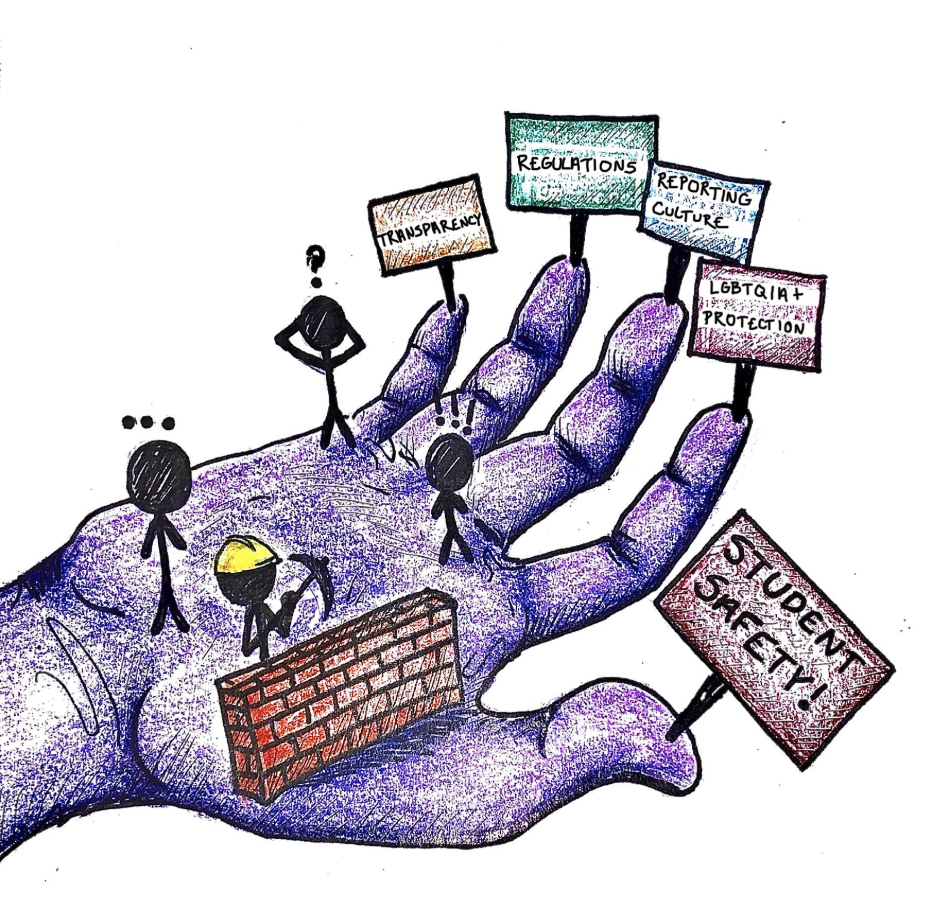

WHAT IS TITLE IX?

Under Title IX, universities in the United States are required to have a process in which sexual assault and sexual harassment allegations are handled. A Trinity student who experiences sexual assault or harassment can choose to take legal action (usually within a criminal court), to allow the university to investigate their case or to decline to move forward with an investigation. The university-led investigation differs depending on whether the responding party (the accused party) is a student, a faculty member, a staff member or a non-affiliated person.

For Trinity-affiliated responding parties, investigations follow either the sexual misconduct policy or the anti-harassment policy. For accused students, the process continues under the sexual misconduct policy. For accused faculty or staff members, investigators follow the anti-harassment guidelines. Both policies cover potential sexual harassment and sexual assault allegations.

Angela Miranda-Clark, Title IX coordinator, explained why Trinity uses different policies to investigate cases. Title IX does not provide institutions with a specific sexual misconduct policy; rather, the law offers basic guidelines set by the U.S. Department of Education.

“So, Title IX is literally 37 words. That is the entire text of Title IX. So all of the ‘What does this mean in reality?’ is provided through guidance from the Department of Education and through case law. Most university policies are very similar [to Trinity’s]. The procedures can change a little bit, but generally the description of the behavior that’s prohibited is very consistent,” Miranda-Clark said.

Because Title IX allows for interpretation, institutions and courts may consult the precedents set in previous Title IX cases.

ACCUSATIONS AGAINST STUDENTS

At Trinity, the process for dealing with cases in which the responding party is a student is standardized for all cases of this nature. Reporting parties can report a complaint in two ways: submitting an online form found at the bottom of Trinity’s website or by contacting Miranda-Clark. Due to recent changes to Title IX, a report can also be made by a faculty or staff member. Mandatory reporters must inform Miranda-Clark if a student tells them about a sexual assault or harassment situation.

Once a complaint is made, Miranda-Clark will reach out to the reporting party to discuss options. The reporting party can choose to wait before starting an investigation or choose to move forward.

Regardless of whether the party wishes to continue with an investigation, Miranda-Clark will offer help in taking care of any of the reporting party’s immediate needs. These can include medical care, mental health care and excusing absences from class. Miranda-Clark also helps the reporting party to switch classes, residence halls or work schedules to avoid the responding party, if needed.

“Whatever it takes to make a student feel safe enough to continue their academic career. So keep going to class, keep turning in homework — not get derailed by whatever incident happened,” Miranda-Clark said.

If the reporting party wants to proceed with the investigation, Miranda-Clark will notify the responding party of the investigation. Then, both parties will each receive an assigned process adviser from the list of trained Title IX investigators to help walk them through the process.

“[The process is] often opaque, so the process advisers help them through that,” said Gina Tam, assistant professor of history and trained Title IX investigator.

There are currently 23 trained Title IX investigators at Trinity, though this number varies each year. All are members of faculty or staff and are required to go to trainings that discuss Title IX and how to enforce it. According to Miranda-Clark, most trained Title IX investigators at Trinity go to national Title IX conferences, but they are not required by law to do so.

Since Miranda-Clark came into her position in April, there have been changes made to the process. Many of the responsibilities that were formerly handled by the David Tuttle, dean of students, or Title IX investigators are now performed by Miranda-Clark. Previously, two trained Title IX investigators would have performed this kind of investigation. Miranda-Clark, by herself or with another individual from the list of trained Title IX investigators, will perform the investigation.

During the investigation, the investigators interview both parties and witnesses, and they investigate crime scenes as needed. The investigation is usually finished within 60 days of the initial report, though the law does not dictate specific time restraints.

“After the investigation has been wrapped up, [the investigators] issue a report. In the report, they recommend — they don’t get the final say, but they recommend — they say, ‘We think these violations, according to Trinity’s handbook, have taken place and that the responding party is responsible for these particular violations,’ ” Tam said.

This report is issued to the hearing panel made up of two new Title IX investigators and one student from the Honor Council. This panel will read the investigators’ report and make sanction recommendations. The decision is passed by majority rule, meaning two of the three individuals must agree on the sanctions.

According to Tam, these cases usually lack physical evidence, making it difficult to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt, as required in a criminal case. Tam emphasized that the burden of proof (the amount of evidence) needed in Trinity’s investigation is less than that needed in a criminal court. Because of this, responding parties are more likely to receive sanctions from the university.

In the old policy, the final decision regarding sanctions was made by the hearing panel. This year, the hearing panel will make sanction recommendations to Tuttle, who will make the final decision.

“The reasoning is … to make sure that there’s an administrator making the final decision and that the decision is in accordance with the school policy in the manner that the cases have been decided in the past,” Miranda-Clark said.

If a party would like to appeal, the report and evidence will be reviewed by Sheryl Tynes, vice president for Student Life, who can choose to keep or change the findings.

ACCUSATIONS AGAINST FACULTY OR STAFF MEMBERS

This process differs from the previous process. Instead of falling under Title IX regulations, this type of misconduct is handled according to the university’s anti-harassment policy. However, the amount of proof needed to decide these cases is the same as the aforementioned sexual misconduct policy.

Unlike the sexual misconduct policy, the university is under no obligation to provide reporting parties with accommodations, such as excused absences or switching out of courses. The policy also does not require that the university offers a process adviser.

“Facilitators are only mandated by the student process, but I imagine that there’s resources for the people under the anti-harassment policy, too. That’s just common to give resources under any sexual misconduct or harassment, discrimination case — answer questions about the procedure, provide accommodations, whether or not there’s a finding that there’s a violation of the policy,” Miranda-Clark said.

Brian Miceli, professor of mathematics and chair of the Faculty Senate, issued the following statement to the Trinitonian about the process of choosing the investigators in these cases:

“In a case where a student makes a formal [Human Resources] complaint against a faculty member, the chair of the Faculty Senate is responsible for choosing two faculty members — the vice president for Student Life chooses a third — to investigate the allegations and then present findings and a recommendation to the vice president for Academic Affairs. Accordingly, the primary function of the chair of the Faculty Senate in such circumstances is simply to find faculty members who are known to be objective and fair, who are not from the same department as the faculty member being accused and who do not have a strong relationship with the accused. If the chair of the Faculty Senate has a strong relationship with the accused, then it is expected that he or she would pass the responsibility of choosing two faculty investigators off to the vice chair of the Faculty Senate. Only the Faculty Senate chair is initially informed about the case, and he or she often chooses to ask for help from the vice chair, but the entire Faculty Senate (20 faculty) is never involved. Moreover, once the Faculty Senate chair chooses two faculty for the investigation, his or her role ends; the chair does not find out when the case ends nor does he or she learn of the outcome of the investigation.”

According to Miranda-Clark, this process is different in a few ways.

“It’s slightly different. There’s not a hearing, and the investigators aren’t drawn from the same group. But [the investigators] are assigned, depending on whether the person accused is a faculty or a staff member, and they do receive training on how to conduct an investigation,” Miranda-Clark said.

After investigators write their report, they submit it to the vice president named on the policy. If the responding party is a faculty member, the vice president responsible is Deneese Jones, vice president for Academic Affairs.

“That vice president will be the one reviewing the investigative report of whether or not there was a policy violation and what the appropriate sanctions should be,” Miranda-Clark said.

Tuttle described why the process has been differentiated from the process in which both parties are students.

“Historically, the student reports generally involve other students. The process evolved from a several-paragraph policy in the 1980s and 1990s to what we have now, as we and other institutions learned best practices. Mixing employee policies and procedures with student policies and procedures is challenging and can make the processes confusing. We did consider a One Policy-One Process model years ago, but it didn’t have support from various departments. Now that we have a Title IX coordinator fully dedicated to this, I think it can be reconsidered, though that will be up to [Miranda-Clark],” Tuttle wrote in an email.

Miranda-Clark expressed interest in changing this process in the future.

“We’re always looking for ways to improve the process, and I think it would be beneficial to have one process for everybody, and I think that’s the general way that the world is moving — to have one process for everyone on campus. So my guess is that we’re probably headed that direction. We just haven’t gotten there yet,” Miranda-Clark said.

CAROLINE TRAN’S INVESTIGATION

At the time that Tran filed her complaint,Pamela Johnston, former assistant vice president for Human Resources, was also in charge of managing Title IX cases. Tran was not offered accommodations after filing her complaint since it was filed under the anti-harassment policy as opposed to the sexual misconduct policy.

“That would have been important because there was a lot going on academically and a lot going on with this complaint. It would have been so helpful to have more flexible deadlines because I was pretty much working around this whole complaint process, and the complaint process took more time and took priority over my school work,” Tran said.

Tran was also not offered a process adviser after making her complaint.

“It would have been helpful to have a facilitator because as a student, I just didn’t know my rights,” Tran said.

Tran filed her complaint in Aug. 2018, completed her written statement in Sept. 2018, and in Oct. 2018, Tran withdrew from Trinity.

The final verdict was given in Dec. 2018. The university found Urbach not guilty of violating the anti-harassment policy. However, his actions were found to be “inadvisable and unprofessional,” according to a letter from Jones, posted by Tran in the Twitter thread. In the letter, Jones added that Urbach’s “conduct did not align with the university’s expectations of professional conduct for faculty.”

When the Trinitonian reached out to Urbach, he provided the following statement:

“Thank you for your email. Out of respect for the student and the process, I have no comment at this time.”

This fall, Tran re-enrolled at Trinity.