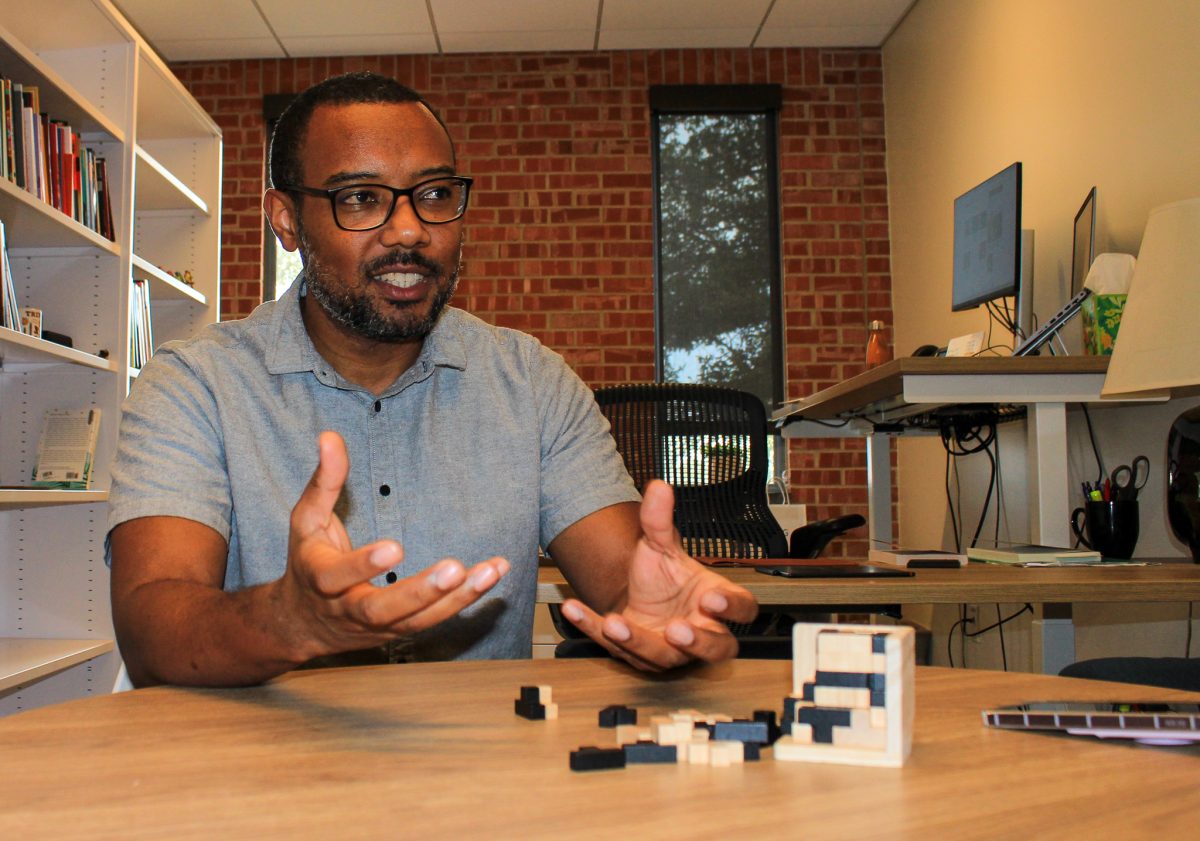

Photo by Oliver Chapin-Eiserloh

This past Monday afternoon, sophomore Kennice Leisk and junior Rebecca Kroger sat at the corner of a long table in Northrup 303. Their laptops were pushed together, and on their screens was a picture of a twelfth century commentary on Virgil’s Eclogue 7, along with an approximately 900-word Google doc — their transcription of the original Latin manuscript, a semester’s worth of work. Kroger and Leisk have been transcribing their text since August, and recently they have encountered a problem: On the bottom of the page, a wrinkle distorts the text, making the ancient handwritten words even more difficult to see.

After a moment of squinting at her computer, Kroger called out to Andrew Kraebel, assistant professor in the Department of English, who stood across the room.

“Why can’t they get a better picture?” Kroger asked.

One wrinkle, rip or smudge can make a big difference for student researchers in the Early Book and Manuscript Lab. There are three sections of the course: While Andrew Kraebel’s is devoted to transcribing commentary on Virgil’s Eclogues as well as a 14th century manuscript of the Gospel of Luke, associate professor of English Kathryn Santos’s students are looking at a print English-Spanish translation dictionary, and classics professor Corinne Pache’s section is working on a medieval manuscript of Homer’s Iliad.

Funded by the Mellon Initiative, the early book and manuscript lab course is new this semester and aims to offer humanities students the opportunity to do detailed, high-level research during the year. A total of 18 students are involved, and their work will be published for future use by academics.

“By working with digital facsimiles, either things that the libraries make available or things that I’ve photographed myself while I’ve been doing research trips, students are able to work on these materials and pay attention to them in ways that scholars have not yet,” Kraebel said. “This is all research that remains to be done, research that the grown-up scholars — folks like me and my colleagues — have not done before.”

While wrinkles and tears on ancient pages create problems, the actual text can also be confusing due to complex abbreviation systems. Even Leisk, who has studied Latin since high school, has trouble.

“Even if we would have known what the Latin word is, sometimes they just do like, ‘o’ with a line over it,” Leisk said. “And you’re like, ‘Oh, you’re supposed to know what that [means],’ but we don’t.”

Leisk collaborates with Kroger on nearly every step, the two students consulting multiple sources and continually checking each other’s work.

“It helps to have two people to be like, ‘Okay, I’ll check this thing for abbreviations, you check this thing to see if it’s even a word,’ ” Leisk said.

Pache’s three lab students are also working on a difficult foreign language text. Their text is a medieval manuscript of Homer’s epic, the “Iliad,” written entirely in ancient Greek. Like Leisk and Kroger, Pache’s students are more interested in the commentary on the poem than the poem itself.

“On each page, you have the poem of the ‘Iliad,’ ” Pache said. “Above it, on its side and below it, there are commentaries. Some of them are from the medieval period, too, from the time of the manuscript, but some of those commentaries go back to ancient scholars, from the Library of Alexandria, for example.”

Pache explained that this manuscript lab is part of a larger initiative called Homer Multitext.

“That’s a project that will seek to digitize all the manuscripts of Homer that we have, but it’s a very slow process. There are several institutions involved,” Pache said. “For the last seven years, a couple of Trinity students and I go to a workshop in the summer where we learn how to do this and participate in the larger project.”

Senior classics major Andrew Tao attended this workshop the summer after his sophomore year, and is now involved in Pache’s lab.

“I think Dr. Pache just advertised the course, and I thought it would be interesting to do in a setting at Trinity, with other students,” Tao said.

Santos’s section of the Early Book and Manuscript Lab is slightly different, since her five students are studying a printed book. Their text — an English-Spanish grammar manual, designed to teach English people how to speak, read and write in Spanish — is easier to read than handwritten manuscripts. However, Santos explained that transcribing a guide to the Spanish language published in 1622 is no simple task.

“Oftentimes, words are spelled differently than we would spell them today,” Santos said. “The other thing that’s a feature of this book is, because it’s designed to teach people how to pronounce Spanish, it’s heavily accented in ways that we wouldn’t put accents on Spanish words today.”

Sophomore Jacob Perry has worked with Santos all semester transcribing the book. His seven years of experience studying Spanish have helped him take on the task, but he is occasionally frustrated by the book’s strange orthography — how the letters are written.

“It’s odd, to say the least. ‘S’s and ‘f’s look very similar, words are spelled just very inconsistently and there are funny stylistic substitutions that the author will use a lot,” Perry said.

Despite its quirks, Perry views the text as a genuine attempt to understand another culture.

“Of course, there are little funny inconsistencies like [when the author writes], ‘The Spanish tend to do this,’ which is kind of, maybe not necessarily racist, but a generalization that we probably wouldn’t insert these days. But I’ve always been more interested in that it’s a very genuine attempt to connect,” Perry said.

All three sections of the lab plan to continue their work next semester.