Graphic by Quinn Butterfield

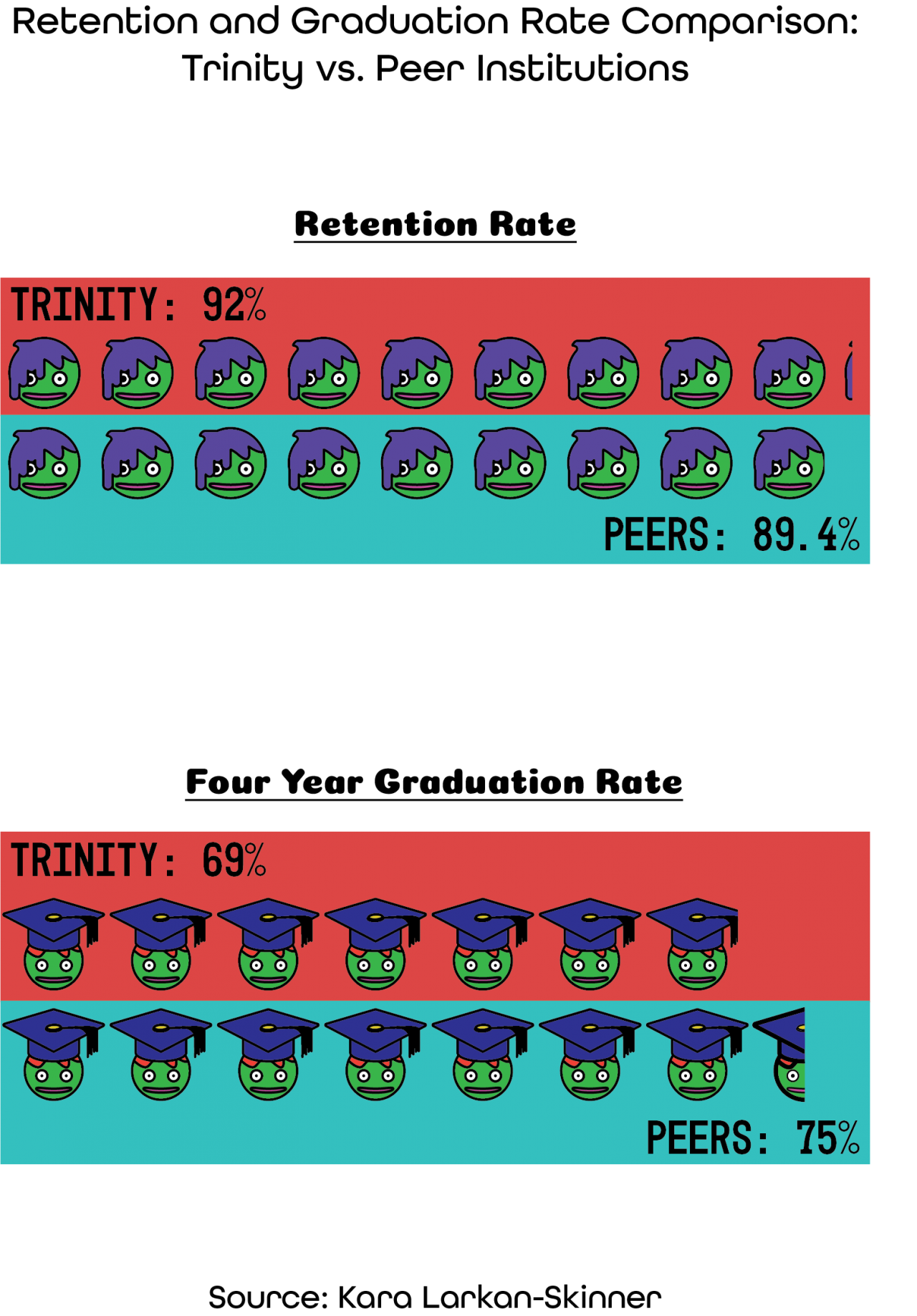

As of 2019, Trinity’s four-year graduation rate is 69 percent, and the retention rate from first year to sophomore year is 92 percent. Compared to peer institutions, or universities that look like Trinity in terms of size and type of school, Trinity’s graduation rate is low. Peer institutions average a four-year graduation rate of 75 percent as of 2017, according to Kara Larkan-Skinner, executive director of Institutional Research and Effectiveness. However, Trinity retains slightly more first-years than peer institutions, which average 89.45 percent as of 2017. The 2019 statistics from the other institutions have not been measured or released.

Trinity uses retention rates and graduation rates as a measure for student success. This semester, a team (including staff and faculty members) has been created to make policy and large scale changes at Trinity with the hope to increase retention and graduation rates.

Retention rates measure the retention of first-year students from fall semester to their sophomore fall semester. The four-year graduation rates measure the percentage of students that graduate within four years. The six-year graduation rates measure the percentage of students that graduate within six years or less. This includes the students counted in four-year rate, and Trinity’s six-year graduation rate measuring the 2013 cohort was 76 percent. Institutions are required to report these statistics to the federal government.

Trinity also compares itself to the top 25 liberal arts colleges in the nation. These universities have an average four-year graduation rate of 86 percent and average retention rate of 96 percent.

“If you look at us across the nation, we are a top performer for retention and graduation rates. What we tend to do, though, is we tend to look — we have a group of peers that we compare ourselves to. Within those groups, we don’t perform as high as we would like,” Larkan-Skinner said.

According to Michael Soto, associate vice president for Academic Affairs concerning student academic issues and retention, these measurements are an important sign of student success.

“If you look at our mission, which is to provide a transformational liberal arts and sciences education with select professional opportunities, we aren’t achieving that mission if students aren’t gaining the full experience of their education here. And if they’re not graduating within a reasonable timeframe, then we aren’t fulfilling that promise,” Soto said.

According to Larkan-Skinner, most Trinity students qualify to be counted in the graduation rates measurements.

“The federal definition is first-time full-time college students. So, if you think about the traditional college student is coming right out of high school and entering into college in the following fall — for Trinity, that is almost all of our students,” Larkan-Skinner said.

These rates can affect and reinforce each other.

“Typically, it makes sense, the higher your retention rates are, the more likely you are to graduate right, so it’s really challenging to have a high graduation rate if you lose students your first year,” Larkan-Skinner said. “So, that’s one of the reasons we focus a lot of our time and energy in that retention rate is to try to keep them here. There’s a lot of research showing that if students stay their first year, they stay to graduate.”

Though the Pathways curriculum has made it harder for some students to graduate in four years, Soto does not believe that this has had a significant effect on the overall graduation rate.

“We’ve seen our four-year graduation rates fluctuate between 65 and 73 percent over the last decade, and since Pathways was implemented, the trend has been slightly improved, but I suspect that Pathways was not necessarily directly related to that improvement,” Soto said. “We hope though to continue to improve how we’re delivering that curriculum so that the trend remains headed in the right direction.”

According to Eric Maloof, vice president for Enrollment Management, there are plans in the works to improve these measurements. Specifically, university president Danny Anderson commissioned a consultant, Ruffalo Noel Levitz, in January 2019 to make recommendations for Trinity regarding daily practices and long-term suggestions. Following this, a task force made up of faculty and staff was put together.

“We did a deeper dive with those suggestions and engaged the campus more broadly with some of those suggestions,” Maloof said.

This process was completed at the end of June.

“From that, President Anderson commissioned an actual retention and graduation rate implementation team to start to come up with action plans for each of these suggestions,” Maloof said.

This implementation team is working to make a timeline and plan to implement these suggestions. The number and timeline are unknown at this point. The changes will be coming out on a rolling basis.

“Some are easier to implement than others, if that makes sense, particularly as it relates to a timeline. Some, we think, will have a greater effect on moving the needle than others as well, so it’s all about prioritization and timeline. We can’t do everything at once, unfortunately,” Maloof said.

One of the changes that have been rolled out by the implementation team is the reduction in GPA requirements to maintain merit aid.

“The key to this is that we all want our students to be successful, and what this group has tried to do is identify unnecessary obstacles that have been unintentionally placed through a student’s journey over time and tried to smooth or remove those obstacles for students. That is something that any top tier university is doing,” Maloof said.

As of now, there is no timeline for the anticipated changes.