graphic by Quinn Butterfield

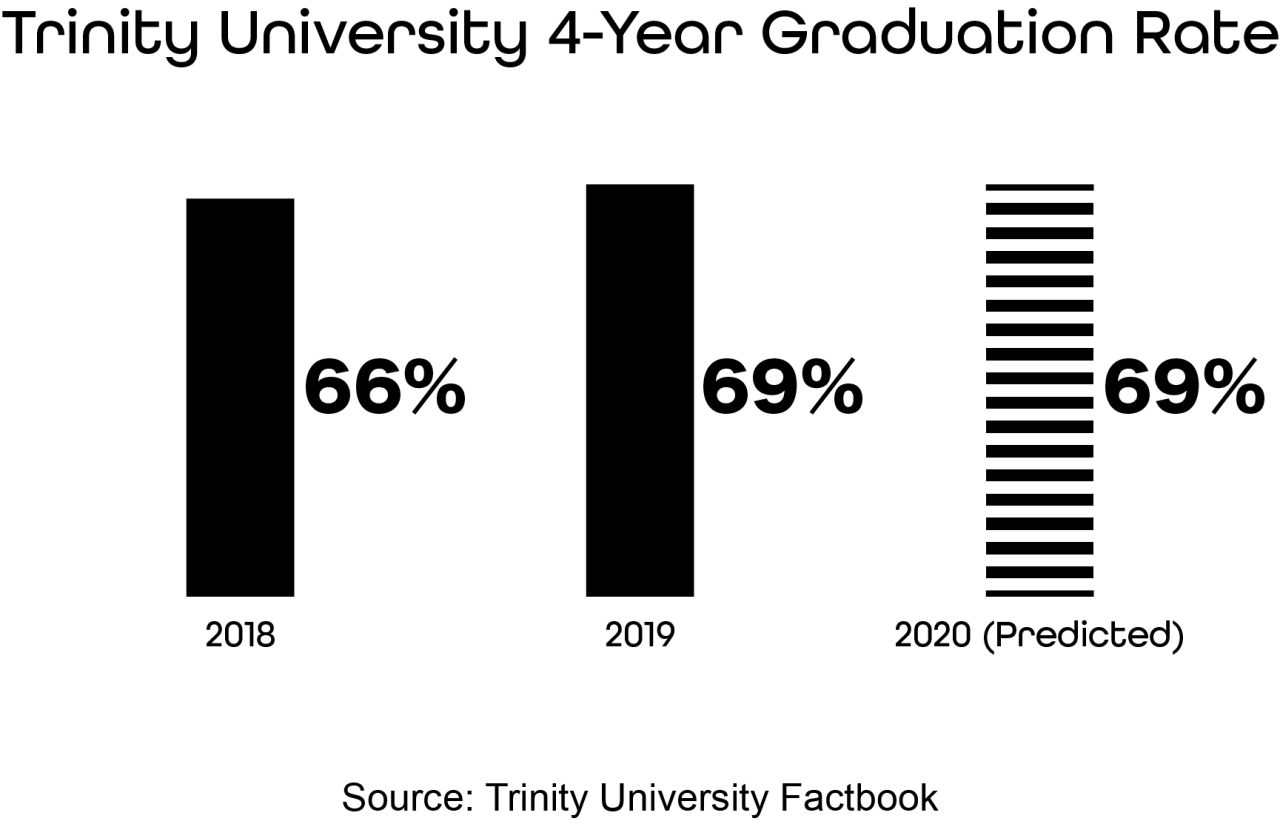

After a three percent increase in the four-year graduation rate between the class of 2018 and the class of 2019, the class of 2020 is projected to graduate this year at around the same rate of 69 percent. Despite the improvement, Trinity leadership believes that this rate is still too low.

Trinity’s leadership acknowledges the difficulty that some students have with the Pathways curriculum and think that this problem requires structural change. Policies are being put in place to address the issue from multiple angles.

When Trinity publishes its graduation rates, the number given specifies the percentage of students that graduated after six years. six-year rates are not reflective of four-year graduation rates, however, as there is often variation between them. According to Kara Larkan-Skinner, executive director of Institutional Research and Effectiveness, both the four- and six-year rates have stayed within the same ranges for the past few years.

“In 2019, the four-year rate was 69 percent. Actually the four-year rate increased, it was 66 percent the year before that. The six-year rate has held pretty steady — we have been at 76 percent for a couple years,” Larkan-Skinner said.

While Trinity’s graduation rate is comparable to that of many universities, there is acknowledgement that it is markedly lower than those of direct competitors. Michael Soto, an associate vice president for Academic Affairs, explained the importance of striving for improvement, particularly in terms of four-year graduation rates.

“We compare very well with universities of all sizes, both very large and very small. Where we need to better is comparing favorably with the very best universities in the country. Trinity’s long-term goal is to find a place among the top 25 liberal arts and sciences institutions in the country. When we start comparing ourselves with that select group of institutions, regardless of size, we are not meeting our goal when it comes to four and six-year graduation rates,” Soto said.

Larkan-Skinner also said that while Trinity’s graduation rates are satisfactory when compared against large samples, the rates should be higher given Trinity’s rigor and quality.

“When you look at the larger context, if you took us and compared us to all universities, we would be in the top one percent of performers, we are a high performer in that way. But we are not like every other institution – we are a competitive, a high-quality, a rigorous institution, and we should have higher graduation rates than a large state school, for instance – and we do. When you start to narrow down to institutions that are like us, we do perform similarly. Our graduation rates are slightly lower than our peer group, but not substantially – but we want to be at the top of the pack,” Larkan-Skinner said.

Both faculty and administration have been working to improve the issue, and a slew of policy changes are to be rolled out within the coming months to aid students in graduating on time, according to Eric Maloof, vice president for Enrollment Management.

“The initiatives are, at its core, trying to provide a seamless path for students to graduate. Some of these initiatives involve looking at our academic policies — there may be unnecessary obstacles in the way of you getting to your degree in four years. Some of them could be financial policies, that are again unnecessary obstacles and prove to be detrimental in a student’s journey through their Trinity experience,” Maloof said.

Some of these initiatives have already been rolled out, such as lowering the GPA requirement for merit-based financial aid.

What we found was that people were worried about losing their merit scholarships, and we should not be in the business of taking away financial aid for our students if they are making satisfactory academic progress,” Maloof said.

Soto also outlined the other efforts being made to ease students’ paths to graduation.

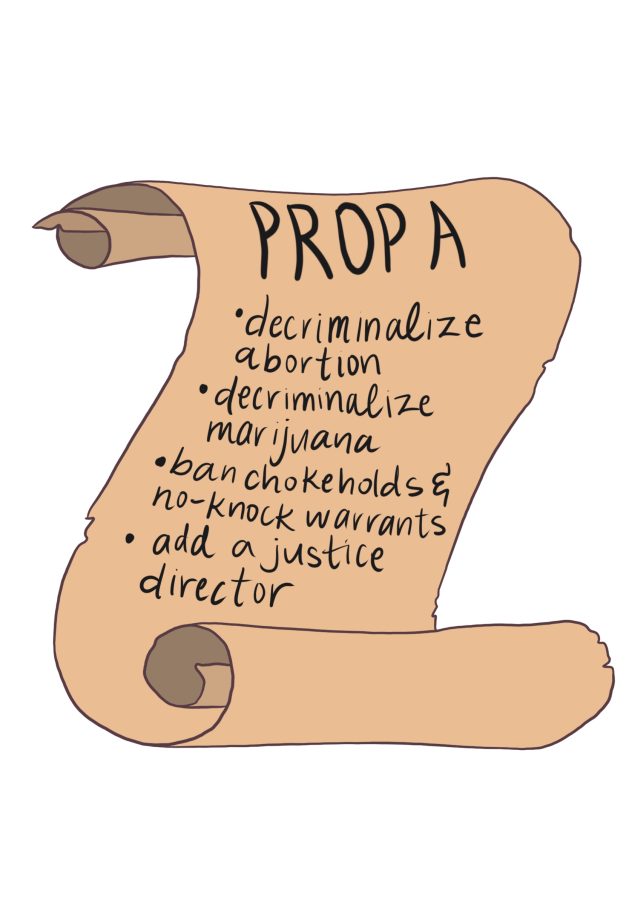

“The University Curriculum Council is exploring alternatives to the Interdisciplinary Cluster requirement, for example. Whether or not the clusters remain a part of the Trinity curriculum going forward, that’s still on the table. It may be replaced by something else that is meant to offer a comparable but maybe more manageable experience,” Soto said.

In addition to potentially removing the cluster requirement, administration is also reworking its approach to advising, as well as many other policy changes.

“Student Financial Services has already revamped the process for evaluating scholarship eligibility. The faculty will be considering some changes to graduation requirements on Feb. 21 — things like the number of credit hours required to graduate. These are things we can do very quickly without sacrificing academic rigor that will still improve the experience and hopefully the outcomes of Trinity students. We are going to be revamping first-year advising beginning this coming fall. We are going to be bringing in a contingent of professional advisors that will work very closely with incoming first-year students and will follow them until those students declare a major and are assigned an advisor within that academic department,” Soto said.

Soto concluded by stating the degree requirements for majors are also being reevaluated in order to ensure accessibility and transparency.

“We are looking at making the curriculum more transparent by simplifying and regularizing the way that degree requirements are laid out for each major. We are always looking at which courses are in high demand and which curriculum bottlenecks we can help to alleviate. We are always trying to improve classroom instruction and to make sure that our faculty are up to date with the latest and best practices,” Soto said.

While Trinity’s graduation rate is a cause for concern in some respects, according to Larkan-Skinner, the improvements being made will likely not be seen in the statistics for some time, given the nature of the data.

“Graduation rates, we call them a lagging indicator. We are making a judgement right now on our graduation rates, but we are judging that on a group of students that started four or six years ago, so 2013, 2015. That is a different group of students than what is here today, and that is because it is lagging,” Larkan-Skinner said.

It is for that reason that the projected four-year graduation rate for 2020 is similar to that of previous years.

Administrators hope these efforts with produce better four and six-year graduation rates in the coming years.

“Trinity is hard, and the balance we are trying to strike is how do we as a university help our students and meet them where they are during their time through Trinity, without diminishing the rigor of a Trinity education,” Maloof said.

ali tosay • Feb 28, 2020 at 12:58 am

haha nice.