Illustration by Andrea Nebhut

IIn the midst of all the blockbuster movies that saturate theaters, there are the lesser-known, independently developed films that can be more emotionally and mentally gripping than the money-grabbing Hollywood entries.

“Honey Boy” is a shining example of one of these works of art, maintaining utter simplicity in its premise but speaking volumes with its themes and messages.

When beginning “Honey Boy,” I had absolutely no idea what it was about. I knew two things: It has Shia LeBeouf, and it may or may not be about Shia LeBeouf.

I soon realized that the movie is quite literally an autobiography detailing the relationship between LeBeouf and his dad.

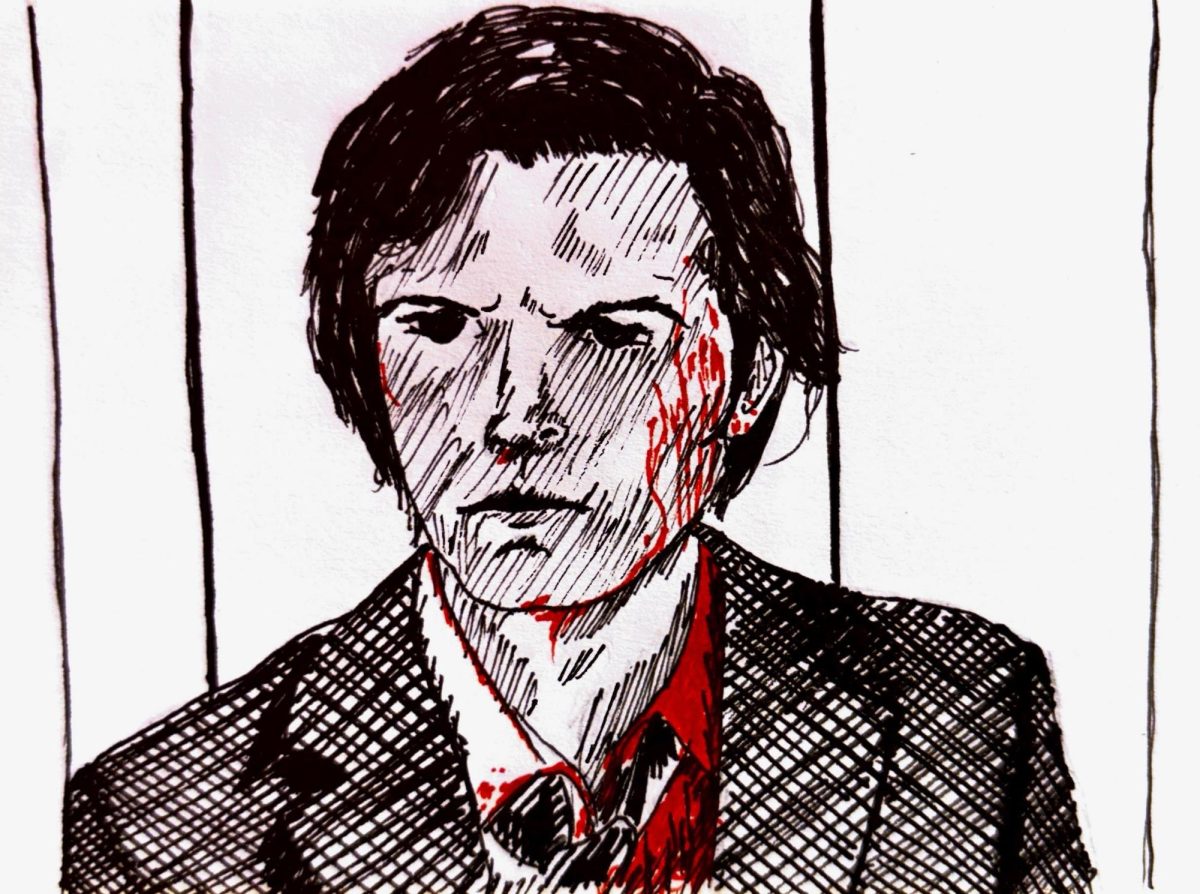

What makes this concept more impactful is that LeBeouf plays his own father, an addict of drugs and booze, that tags along on his son’s acting career, or rather, the money it comes with, cursing and lecturing the entire way through.

Indeed, throughout much of the movie, we come to despise the father.

But for every moment in which that borderline cruelty occurs, the main character Otis, played by Noah Jupe, still conveys his love and devotion to his father.

It becomes evident that this is a complex dynamic between a growing boy and a father who drinks too much and hits his son, a father that Otis does not deserve. Otis comes off almost entirely as an adult, working through and confronting the issues he has with his father, but he ultimately must recognize that he is still vulnerable to his father’s verbally, and at one point physically, abusive tendencies.

And this interaction is the core focus of “Honey Boy.” In fact, its really all we ever see in just a hour-and-a-half run time.

But the harsh love, bitter hate and momentary friendship that this father-son duo alternate between is so gripping that it’s all the movie needs to be successful.

Yet, the main theme of the movie still soars past that dichotomy. I haven’t even touched on the fact that this storyline runs parallel to that of an older Otis, played by Lucas Hedges, who has also become an alcoholic and is placed into rehab where he is forced to confront the darker relationships of his past.

Director Alma Har’el executes brilliant symbolism between these two storylines.

For instance, while adult Otis dips his feet in the pool at the rehab center, demonstrating his hesitance to jump in and embrace who he is, young Otis jumps headfirst into his neighborhood pool as he continues his struggles to find a solution to the hard relationship between him and his father.

Har’el litters the film with these kinds of symbols and images that culminate beautifully in the film’s finale.

The pairing of the past and present of the love-hate relationship between father and son is where the main theme of “Honey Boy” becomes prominent.

I don’t know what was running through Shia LeBeouf’s mind when writing this film, but I believe I have deciphered what he is trying to get across: that no matter how dark one’s past or how rocky parental relationships can be, there is no complete escape from where you are from. And to fully realize this notion, one must embrace and confront that past, a concept which young Otis attempts (and fails) and which adult Otis is now scarred by and afraid to do.

“Honey Boy,” in essence, is a memoir. A beautiful and almost tragic ode by LeBeouf to his own past that quite honestly made me see one of what I believed to be the snarkiest of actors in a new light. His performance as his own father is both cathartic and honest. While portraying some of the more negative emotions his father brought out, LeBeouf seems to also acknowledge more positive moments.

And that honest and real representation of human emotion is why I give it such high praise, and likely why, despite its small release, critics and audiences alike were pleased to see what can only be described as an emotional work of art played out before our eyes.