Illustration by Gabrielle Rodriguez

This article is a part of the Trinitonian’s coverage of Trinity University’s response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Click here to read the rest of our coverage.

Associate professor of music Brian Bondari’s Keyboard Skills IV lab met its immediate end after students returned from Spring Break. The lab had depended on Trinity’s many available pianos and keyboards, and this availability was no more.

“Once we had to go our separate ways and evacuate campus, not everyone has access to a piano where they are now,” Bondari said. “How in the world was I supposed to continue that class in a fair and equitable way, when not everyone could even perform any of the exercises on a keyboard?”

After consulting with the Department of Music, Bondari decided that the students would keep the grades they had at midterms, and the lab would end.

Of course, the majority of classes are continuing despite the lack of access to Trinity’s resources. But the switch to remote learning hasn’t necessarily been easy, and in numerous disciplines, professors are having to alter the way they teach.

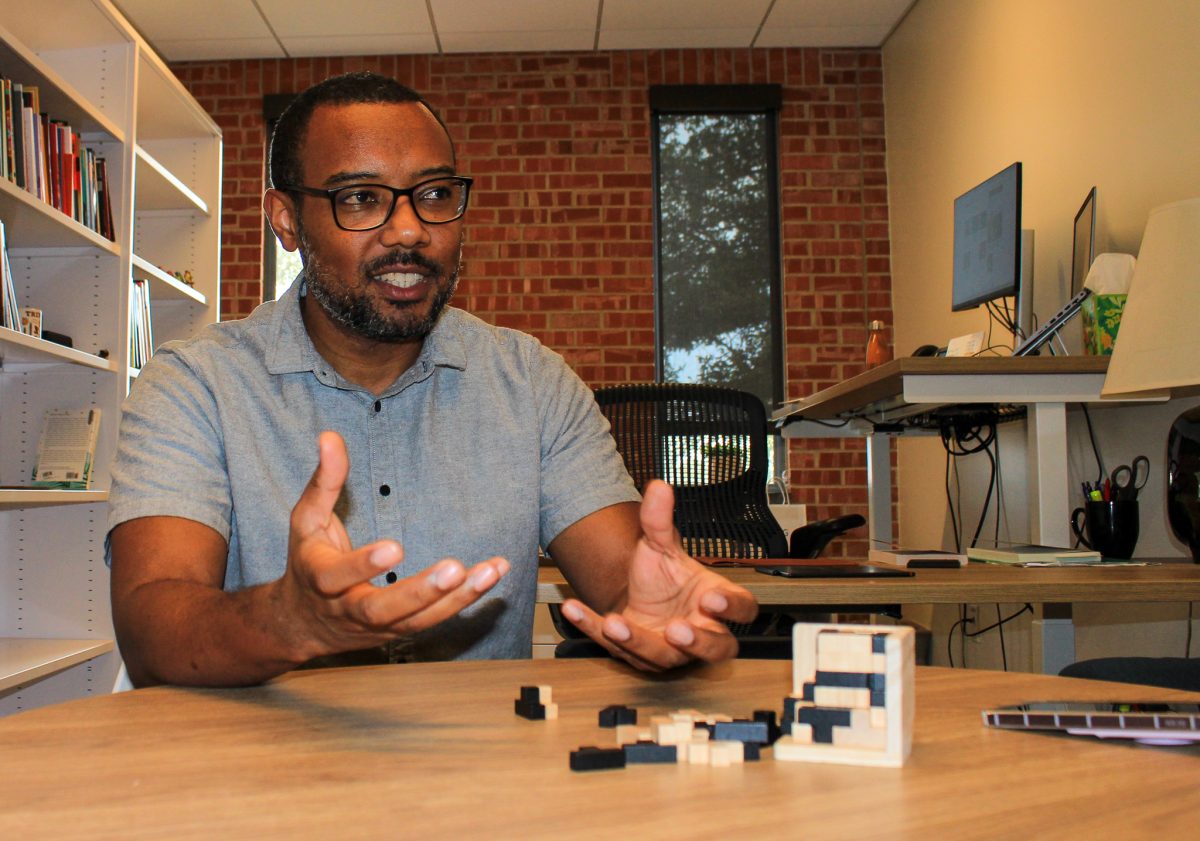

Professor James Shinkle’s Introduction to Biology lab is still happening virtually, but instead of using Trinity’s facilities to conduct experiments, students in his class now depend on various websites that aggregate biological data. The first week after returning from Spring Break, the lab worked with a website called iNaturalist.

“This is a way to aggregate data from people who just want to go out in the field and observe plants and animals,” Shinkle said. “Where they are, what state of their life cycle that they’re in … Are the squirrels gathering nuts? Are the flowers flowering?”

Students went into their own backyards and neighborhoods, observing and recording what they saw. The data was then uploaded to the iNaturalist website, where it could be curated by a group of specialists.

In the following weeks, the lab worked with Nature’s Notebook, a product of the United States of America’s National Phenology Network (USA-NPN), and then Bash the Bug, a project studying strains of tuberculosis developing antibiotic resistance.

“[Bash the Bug has] all these images and a small staff, and so they put this on the web and said, ‘Please help us,’” Shinkle said. “Now, according to their site, they’ve gotten over a million pieces of data classified by their crowdsourcing.”

All of these websites fall into the category of “citizen science” — scientific research conducted, in whole or in part, by amateur scientists.

Visiting assistant professor Kristina Trevino teaches a variety of courses in the Department of Chemistry, including Chemistry in Everyday Life, which is designed for non-majors.

“That class wasn’t hard to do because the labs are … elementary, very basic,” Trevino said. “However, it’s hard for [the students] because they are not science-minded. So there are things that they don’t understand that are very basic in the science community that you really have to take a lot of time to explain very clearly.”

Chemistry in Everyday Life had three labs left in the semester. Trevino decided to drop one of them due to lack of time. For the remaining two labs, she conducted one on video for her students to watch, and for the final lab, she mailed students material to complete it at home.

“It was an acid-base lab where they had to take the pH of different chemicals in their house, ice tea or drain water from the faucet, whatever it was, and then they had to do the lab,” Trevino said. “I gave them two weeks to do it, versus coming in and doing it right in an hour in class.”

Trevino’s Advanced Chemical Principles lab is composed of mostly juniors and seniors, who know the ropes of the department. However, that class requires students to design experiments of their own. A key component of the course is conducting the experiments to see if they actually work.

“That class was very difficult because they weren’t allowed to do [the experiments] to see where their protocol that they came up with was incorrect,” Trevino said. “We did not drop any of those labs. We kept them, but we had [the students] design the entire experiment. And then we provided each group — because they work in partners — a different set of data.”

The students critiqued the data instead of the experiments. Then, they were required to do research to see how their experiments were normally done.

“We required them to do a lot of literature research to see … if what they had proposed came close to how it’s actually done where it would work,” Trevino said.

When it comes to quizzes and tests, Trevino said she has begun to treat cheating as an inevitability. She requires her students to pledge their work but doesn’t take preventative measures beyond that. Giving too short a time to complete a test or quiz might be unfair to students with a slower Internet connection.

“It’s happening, and I can see it, and we talked about this as a department,” Trevino said. “[In] chemistry, every part — [general] chem, [organic] chem, [physical] chem, inorganic, analytical — it all builds up; you have to use some part of every chemistry in those classes. So right away we had to swallow that pill and say like, you’re gonna cheat. But there’s nothing we can do about it, and it’ll come out in the wash later.”

Due to the cumulative nature of chemistry, the department is also strict about providing the pass/fail option only to those who truly need it.

“Let’s say [a student is] in Organic 1. We can’t let them take it pass/fail because if they’re barely passing and made switches to a pass, they’re not going to have enough with that pass to get through Organic 2,” Trevino said.

Bondari also has his students pledge their music theory exams, and he uses a randomization feature so that no two tests have the exact same questions. He said he trusts that students won’t cheat.

“I take the students at their word for something like that,” Bondari said.

Bondari has also found workarounds for his music composition class, where he uses an open-source software called Open Board to annotate and share PDFs. Most of all, though, Bondari misses the in-person rapport he developed with students.

“Overall, I think you’ll find that most of us are reluctant online instructors,” Bondari said. “I don’t think I’ll take for granted, in the future, the small class sizes and being able to meet with those students.”