COVID has increased our culture’s awareness of healthcare workers. Essential workers are constantly exposed to the virus, making them vulnerable. Without decisive action from local, state and national governments, COVID numbers continue to rise. This is putting a major strain on hospitals. In hot spot areas, hospitals do not have enough staff, ventilators, beds, or sometimes even morgue space.

Gabriella Lopez, a candidate for a master’s in healthcare administration, said, “when we were seeing a national shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators, the task to help secure that equipment fell onto hospital administrators.”

A lot of background work goes into making sure a hospital runs smoothly and can help people.

“Often, people are confused about the role of the healthcare administrator because they are only familiar with the front line works (doctors, nurses, techs, etc.). Healthcare administrators work to support those clinical functions as well as environmental services, laboratory, revenue cycle, food and nutrition, billing/coding, etc.,” Lopez said.

Administrators are some of the unsung heroes of our time.

“They continue to work round the clock with their COVID-19 command centers, front line workers [and] state/local officials to ensure communities are receiving the appropriate care they deserve,” Lopez said.

The logistical work behind running a hospital may go unnoticed, but it is an essential and highly skilled job. Helping people goes beyond the care between doctor and patient. Hospitals are a large network of different departments that depend on each other to run smoothly. “It takes a village,” Lopez said.

COVID-19 has impacted the field in innumerable ways.

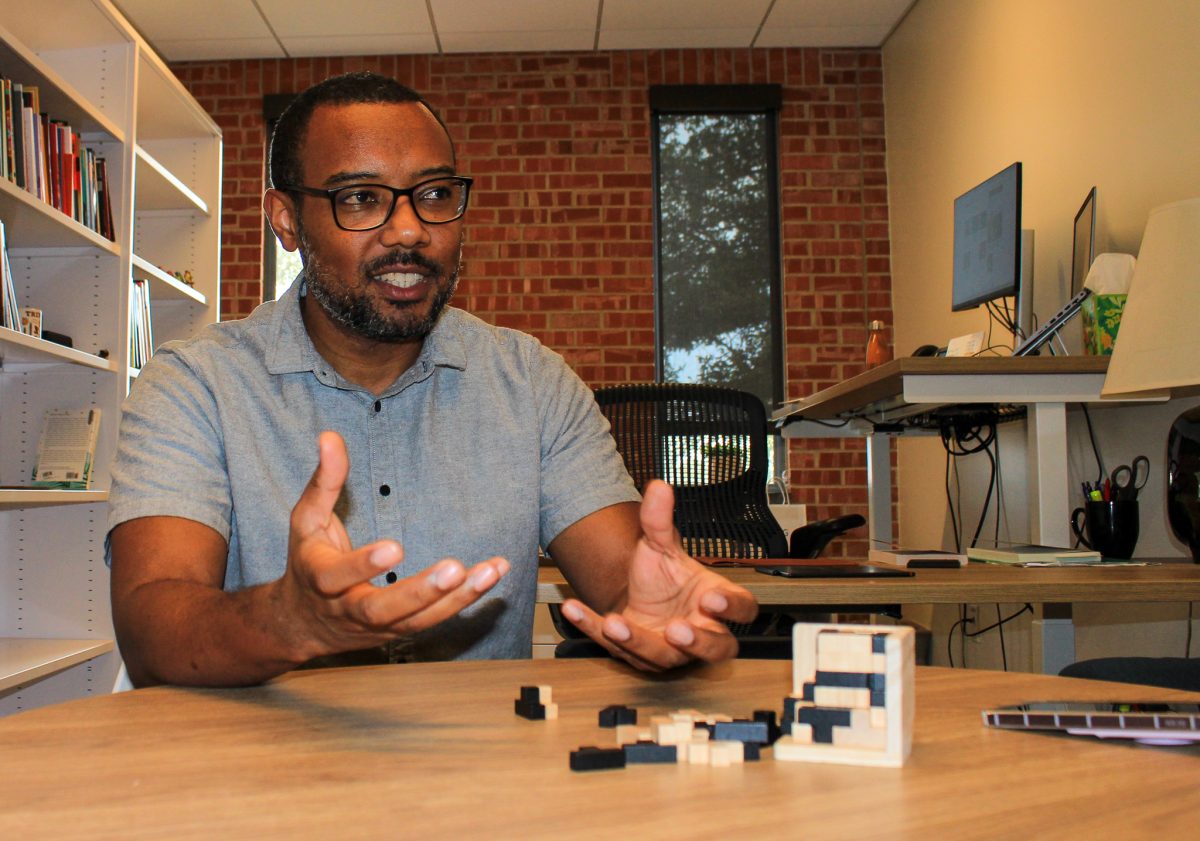

Dr. Schumacher, the department chair for healthcare administration, said, “[COVID-19] really highlighted the inequities in our health system. We’ve known that inequities across race, socioeconomic class and COVID has revealed that the healthcare system is really lacking.”

COVID has amplified the existing problems within healthcare.

“Historically, the health system and public health have been independent arenas…there hasn’t been interaction and COVID has exposed the danger in that,” Schumacher said.

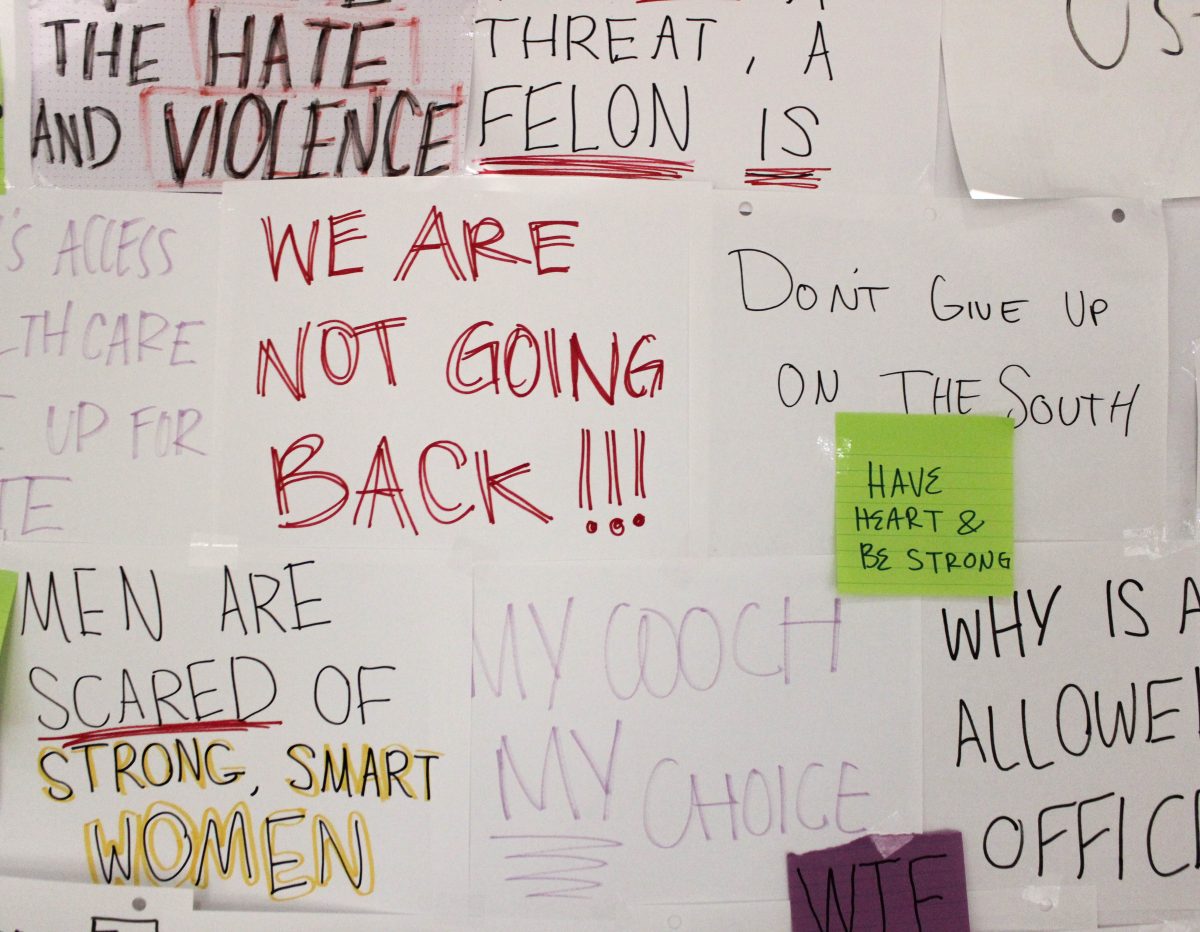

Healthcare administration students are deeply interested in resolving these inequities.

“I was born and raised in a low-income community and witnessed what happens when communities have poor social determinants of health and how that plays into their healthcare journey long term,” Lopez said.

Moving forward, the field will evolve to include public health issues and bridge the gaps of healthcare that hurt marginalized communities.

Graduate students are already getting a hand at trying to bridge public health and healthcare administration.

Sabrina Arizaga, a graduate student and Trinity graduate, said, “I worked with Katherine Hewitt, Trinity’s Wellness Coordinator, on developing a public health campaign for a safe reopening in fall 2020 while working with the evolving state and county public health guidelines.”

Arizaga and Lopez both worked on Trinity’s public health campaign, ProtecTU. The campaign’s goal is to help Trinity students keep our campus and wider San Antonio community safe.

“Our small team within the larger Health and Wellness team collaborated with Trinity’s Strategic Communications and Marketing department, epidemiologists, professors and others to create COVID-19 educational and training material and the ProtecTU Health Pledge,” Arizaga said.

Entering the job market is already scary for any college graduate but even scarier during a global pandemic that is causing major layoffs. Despite the stressful situation, the graduate students are looking optimistically towards the future.

“This pandemic has only highlighted some of the disparities in our healthcare system. Because of this pressure, the healthcare industry is experiencing tremendous change right now, and I hope to be part of the solution as a future healthcare leader,” Arizaga said.

Lopez shares the same sentiment.

“I feel privileged and honored to get to be a part of something so much larger than myself,” Lopez said.

Trinity’s graduate program is 28 months long, with a 12-month residency at the end of the program. Students had to postpone their residency processes, which would have originally begun in May.

“We were very nervous and anxious about the residency search process at first since we didn’t know if hospitals would still be looking for residents since many hospitals were being negatively impacted financially by COVID-19,” Arizaga said.

Students like Lopez and Arizaga exemplify the young administrators who want to improve the field and make healthcare more accessible for everyone.