Conversing with Barbara Hepworth’s magic stones

The sculpture is one of four castings worldwide

Barbara Hepworth’s 1973 bronze-cast sculpture, Conversation with Magic Stones, is mythic, mysterious and interactive. Made up of six parts, the sculpture is in conversation with itself, with us and with the landscape on campus.

Rumor has it that studying in the middle of the magic stones will earn students a higher grade. In this way, physical interaction with the sculpture is encouraged: touch, climb, stand or hop from one stone to another, but most importantly, sit and think.

Situated in an outlined circular mound of grass between CSI, Coates Library and Laurie Auditorium, Barbara Hepworth’s Conversation with Magic Stones sculpture at Trinity is actually not the only one of its kind — three other castings exist. One is in a private collection in Switzerland, one is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and the artist’s copy is owned by the Tate Gallery.

Bronze-cast works are reproducible because their creation process involves a mould. Although identical copies of Conversation with Magic Stones exist, Trinity’s copy of the sculpture is unique because of the myth students have attached to it, as well as the space it creates and occupies.

Created in the last few years of Hepworth’s life, the sculpture consists of three tall vertical forms, which the artist described as “figures,” and three squattier horizontal forms, which she described as “stones.”

In shape, the stones are identical eight-sided polyhedrons, but they look different and are hard to recognize as similar because they are situated on different sides and have individual surface details. The bronze stones could almost be mistaken for actual carved stone; Hepworth convincingly makes what was once a liquid material look like rock.

It is interesting that Hepworth described the vertical forms as figures because that term suggests human characteristics. In this way, the parts of the sculpture are in conversation amongst themselves — three figures interacting with three magic stones.

On Trinity’s campus, Conversation with Magic Stones is situated in the middle of a grassy circle (perhaps slightly mounded), outlined by bricks. The circular form carries with it many connotations, one of which is the idea of eternity — a circle has no end and no beginning, there is no way out.

This is an interesting concept that may further deepen the implications of the work, however, you can jump in and out of the circular frame of this sculpture all you want. Hepworth would’ve wanted students to circumambulate (walk around) the sculpture and through the sculpture. To get another perspective on campus, stand on top of the parts of the sculpture (carefully). The interactive possibilities are endless.

The stones create their own space that you must enter into for the conversation to be whole. In this way, the conversation is extended out to the viewer. The “conversation” mentioned in the title is ambiguous, however in one sense, this is a conversation about space — how a person relates spatially to the sculpture and how parts of the sculpture interact with each other.

In a conversation with Alan Bowness, Hepworth explains that she is concerned with scale as it relates to human beings.

Themes that Matthew Gale and Christ Stephens, authors of Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Gallery Collection and the Barbara Hepworth Museum St. Ives, pointed out in the sculpture include social interaction, a concern with social formations and the relationship between individuals, the artist and society, esoteric symbolism, and the combination of metaphysical aspects and human interaction.

For Dore Ashton, writer, professor, and critic on modern and contemporary art, Hepworth’s Conversation with Magic Stones satisfies our need for an origin story:

“The stones I find in Hepworth – whether the bronze analogies in ‘Conversation,’ or real stones – are nearly always the bones of the Earth Mother, carrying their ineffable message of origin. They subsume all of our longings for beginnings; for truths that escape pragmatics.”

In my mind, Conversation with Magic Stones, in conjunction with its setting on Trinity’s campus and its adopted myth, evokes a sense of knowledge — possessed or (more often than not) unpossessed. The stones have answers, although they tend to conjure up more questions. Maybe the sculpture has a sort of power in the hidden wisdom of its parts.

That’s my interpretation, anyway.

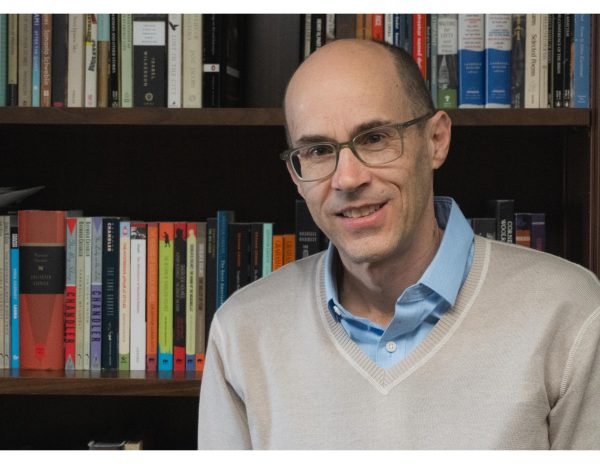

My name is Ashley Allen and I am a senior completing a BA in art history at Trinity University, with a minor in Medieval and renaissance Studies. I hope...