In Texas, books are deadlier than guns

“A book is a loaded gun in the house next door … Who knows who might be the target of the well-read man?” — Ray Bradbury, author, in his book “Fahrenheit 451”

While Banned Books Week took place in the last week of September this year, book bannings are always a relevant topic — especially in Texas. Texas bans more books, by far, than any other state, as revealed by a PEN America report last month, which placed the number of banned books in Texas so far this year at 801. Jasmin Salinas, a librarian at San Antonio Public Library’s Landa Library branch, said there has been a distinct increase this year.

“I have been here for nine years and this is the year we’ve had the most challenges in our collection, especially juvenile materials,” Salinas said. “We usually get [around] one or two challenges a year. We’ve had 26 in the last month.”

The surge in Texas bans can largely be traced to last fall, when U.S. Rep. Matt Krause, R-Fort Worth, sent a list of 850 books to school districts across Texas and asked if the listed books, mainly books by women, people of color and LGBTQ writers, were available in school libraries. The move prompted a legion of parents to approach school districts demanding the listed books be removed.

“There’s definitely a lot more attention on it. … It’s on a lot of people’s radars. I think it’s a lot more of a talking point for the upcoming elections and I just think there are a lot of people looking to find things they disagree with,” Salinas said.

Book banning and censorship is as old as the written word and the United States has a storied history with it. The first literature ban in the U.S. occurred in 1650, colonist William Pynchon published a pamphlet which suggested a way to get into heaven that disagreed with the puritanical Calvinist doctrine of predestination. In 1851, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was published as a depiction of the evils of slavery. The book (along with other books of abolitionist sentiments) was met with furious public book burnings by pro-slavery mobs, and the state of Maryland even jailed a free Black minister for ten years for owning a copy. In the last century, the surveillance of books in schools has become more of a prominent issue, a central battleground to censor what is and isn’t appropriate for young minds.

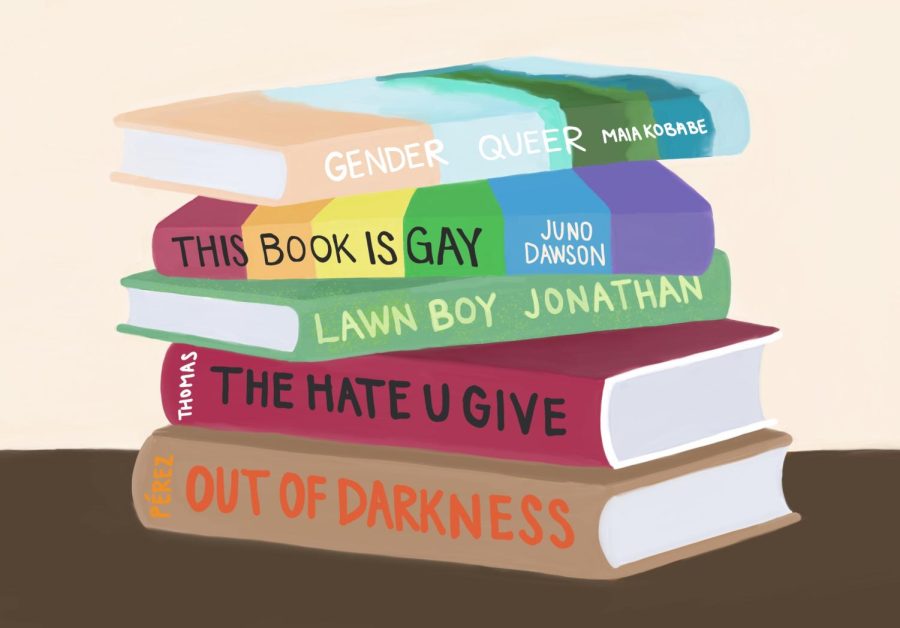

As societal views change over the years, so, too, does the discourse surrounding “appropriate” book topics. According to PEN America, 41% of all banned books in the U.S. deal with LGBTQ themes while another 40% feature main characters of color. Building on a long tradition of prejudice and dignigrating stereotyping that suggests LGBTQ literture is innately more sexual and “pornagraphic,” LGBTQ books are being targeted for reasons of “pornography.” According to PEN America, “Some contain nothing more ‘obscene’ than the mere suggestion of a same-sex couple in an illustration, as in the board book Everywhere Babies, which was … misleadingly labeled ‘pornographic.’”

Another reason for the rise of book banning stems from the coordinated assault on critical race theory (CRT). Former President Donald Trump said in a March speech that “getting critical race theory out of our schools is not just a matter of values but is a matter of national survival.” This echoes the sentiment of conservatives around the state. CRT is not being taught in Texas public K-12 schools, as it is a college-level discipline that looks at an amalgam of critical stances analyzing racism as it’s embedded into the legal and social framework of the country. Whether or not books are technically about CRT doesn’t seem to matter, as it’s being used as a pretext to censor authors of color.

In San Antonio, North East ISD (NEISD) school district banned more books by far than any other in the state according to a Houston Chronicle investigation, removing 119 books this year including the award winning children’s book “Unspeakable” by Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper. The book is a firsthand account of the Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the deadliest terrorist attacks on American soil, in which an unknown number of African Americans were killed and injured by an angry white mob as the affluent majority-Black neighborhood once known as “Black Wall Street” was completely obliterated.

Vicky Liendo, coordinator at the independent bookstore Nowhere Bookshop, explained how they found out about NEISD’s ban on the book and decided to combat the ban by distributing free copies.

“We are [against] the restriction of information and the banning of books. As independent bookstores we do a lot on the ground for getting these books in people’s hands and if we can do something like that to influence — like what we’re doing with this book — we do our part to make them accessible,” Liendo said.

The American Library Association (ALA) challenged 1597 book bans last year, and challenges this year are already set to exceed 2021 as the highest total since the beginning of record-keeping in 2001.

The ALA said in a statement: “Book bans harm communities. Students cannot access critical information to help them understand themselves and the world around them. Parents lose the opportunity to engage in teachable moments with their kids. And communities lose the opportunity to learn and build mutual understanding.”

Hi guys! My name is Lily Zeng, and I am a sophomore from Memphis, TN majoring in Urban Studies with an interest in a Spanish major or minor. My favorite...