Most people have an eminent desire to not be a part of racism in any capacity, but the world we’re living in makes that nearly impossible. The world’s flow of money and information runs through colonial powers, and practically every institution has racism embedded in its foundation.

Case in point: the Smithsonian Institution, a trust instrumentality of the United States and a museum dedicated to the preservation and discovery of knowledge. In other words, it’s a very large museum that most people come to know about after they cite it in a paper or find a cool page on its website while bored. It’s certainly not something people think about about the scourge of racism in America.

In general, the Smithsonian does try to be a positive force in American society, which is evident through many of its articles and exhibits which provide a broader lens of culture and history than is typical of American educational institutions.

Nonetheless, its history is plagued by racism, which came to light this past August when the Washington Post reported on the Smithsonian’s racial brain collection started by early 1900s white supremacists who wanted to pseudoscientifically prove the superiority of white people. These brains were usually gathered without consent and stored in the animal section, and the families and communities of the people they belonged to were never directly informed about the Smithsonian’s possession of these brains.

This illustrates that even organizations that are generally not nefarious can still not only have deeply racist roots but can actively perpetuate racism without necessarily realizing what they’re doing. This is a massive problem on a global scale, but it’s of particular significance in academic fields and institutions that purport to be interested in progress but have also been historically and presently dominated by white men.

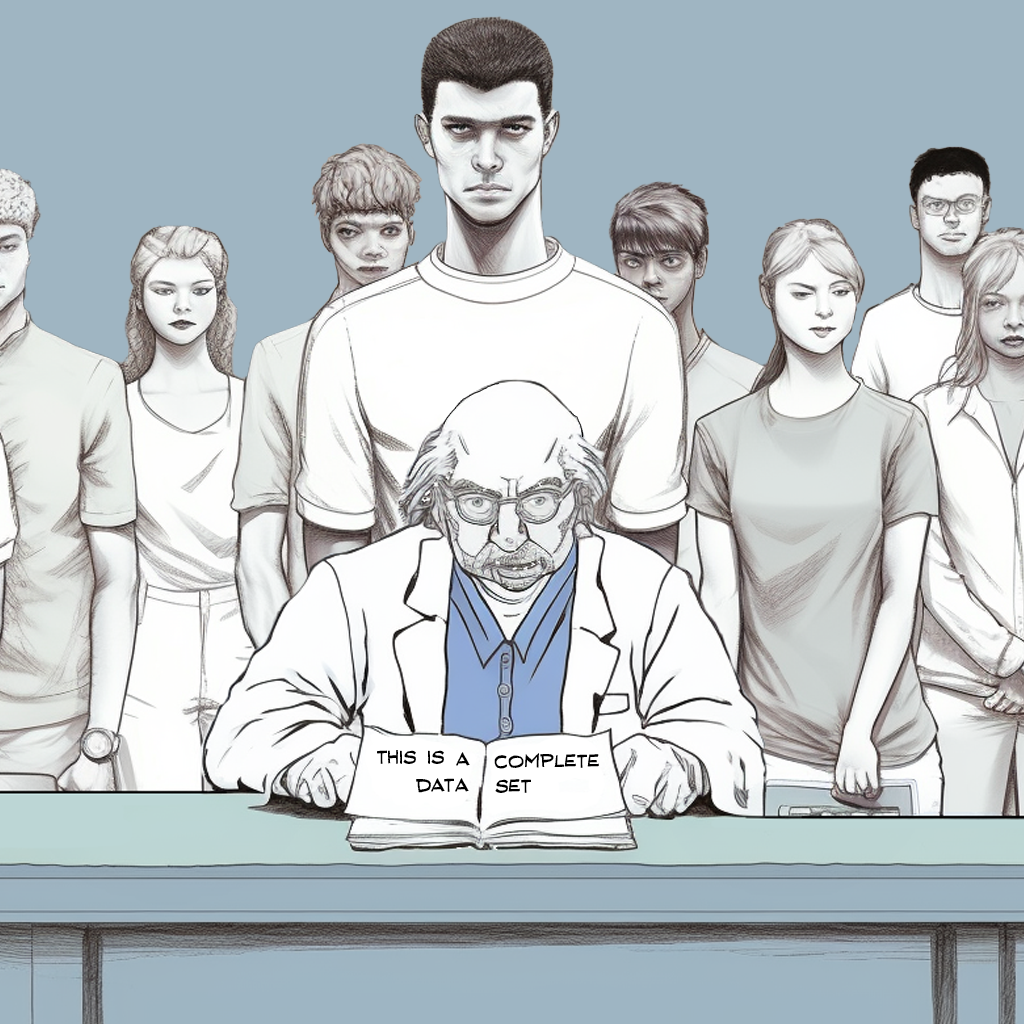

For example, computer science has a major racism problem in its data selection. Data is split into different categories to train artificial intelligence algorithms, which can cause the dataset used and the way it’s categorized to reflect the biases of predominantly white male software engineers.

The medical field suffers from racist roots too, as myths about physical racial differences informed by centuries-old craniometry and eugenics influence the practices of predominantly white doctors to this day. This is a major factor in the rampant issues of substandard medical care and inadequate pain management for people of color.

The study of history is also egregiously affected by racism, as many history textbooks deliberately portray colonial powers positively and minimize or erase events such as America’s genocide against Indigenous people and the invasion of other countries. This is actively happening, fueled further by current Republican efforts to eradicate “critical race theory” from education. This creates catastrophic flaws, rooted in white supremacy, in our collective understanding of the world.

These examples show that the racism embedded in our institutions in the distant past affects people who are not aware of it and who have no desire to be racist themselves. This makes it difficult to justify the position of those who want to stop talking about race, an issue of the past, and focus on issues of the present. Even if every person with conscious bigotry in their hearts cast it away right now, racism would still be an issue of the gift.

People in many academic fields fail to consider how racism affects what they study and learn, as it would seem that much of academia’s concentration is on objective facts. This notion, however, is misguided, as everything about the way we perceive the world is influenced by our culture and society.

There is nothing that is fully free from bias, as everything we accept as fact has gone through countless generations of people trying to understand it. As such, we must take it as a given that everything we understand and the methods we use to understand things could be wrong or misguided, especially with our society’s roots in bigotry being so deep.

When engaging with academia, we must be mindful not only of our prejudices, but the prejudices of the countless people that came before us, and we must be vigilant in looking for problems where they exist. Doing so, such as in the case of the Smithsonian’s racial brain collection’s finally becoming known to the affected families, can potentially present solutions to problems that have existed for decades or even centuries.