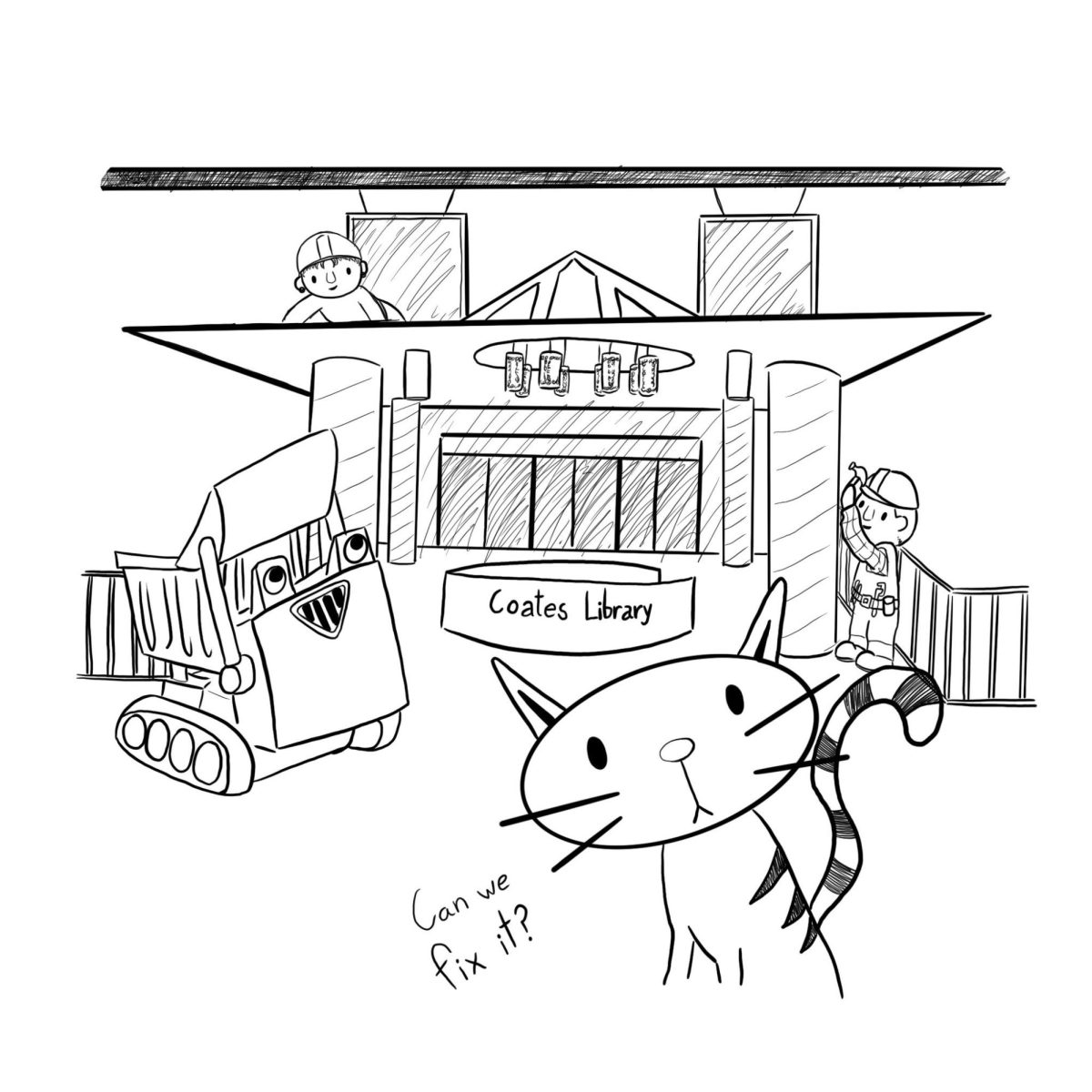

Trinity has continuously put its money towards renovations that prioritize aesthetic appeal over functionality. Due to construction this upcoming semester, the university will be closing parts of campus that are vital towards student mobility, under the pretense that it will create a more vibrant and accessible space. Being disabled and stumbling across news about a new accessible space (so exciting!), I was immediately hooked, only to find that the accessible space refers to the addition of a grand total of one “accessibility ramp” outside of Coates Student Center near the Fiesta Room.

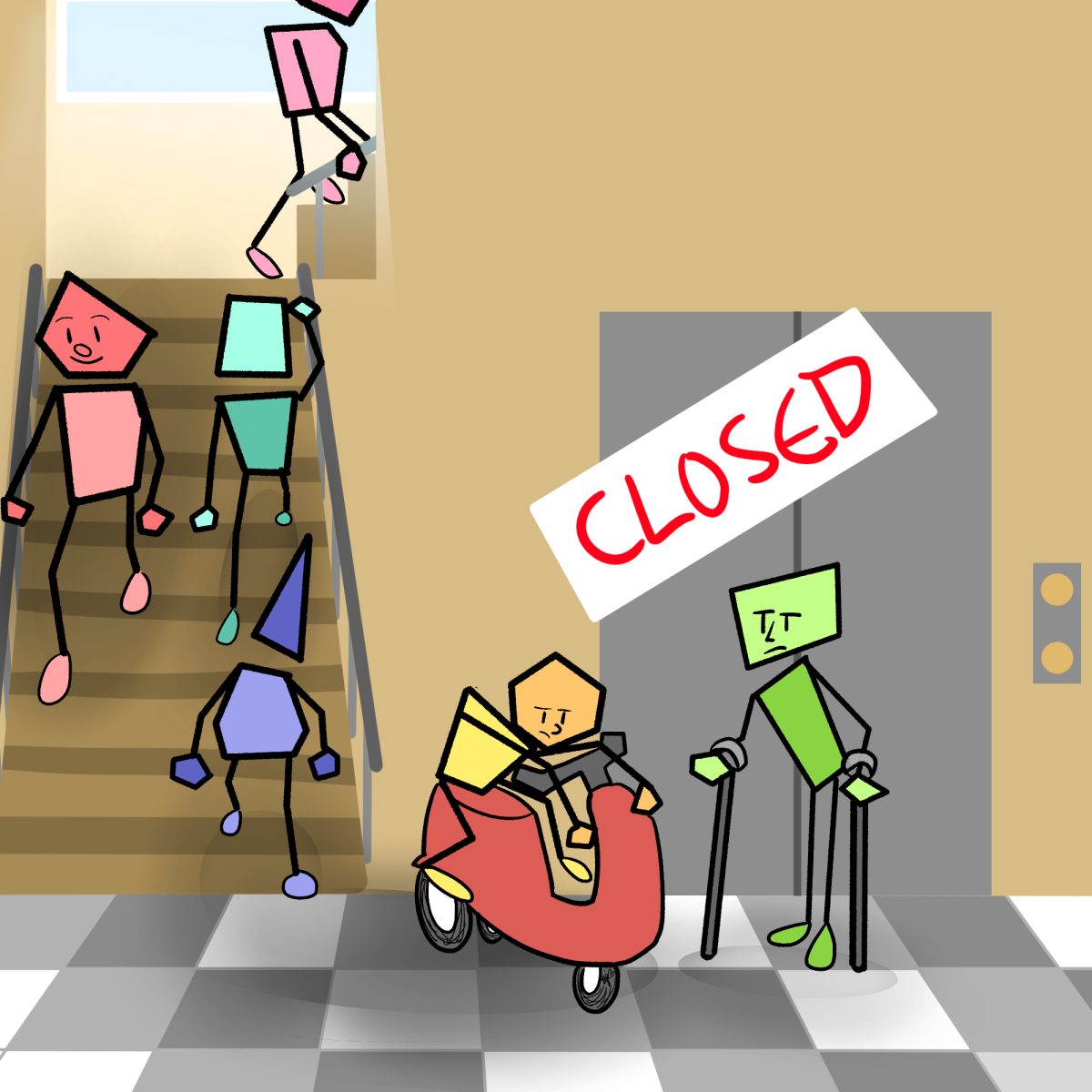

As a result of the construction, students should expect a temporary closure of the elevator in Murchison Hall in November. In addition, the university will be temporarily closing Cardiac Hill for an even longer period of time, which will likely increase traffic to the already overcrowded Murchison elevator. This is problematic because the elevator, meant for students who are physically impaired, will probably be full of students who don’t want to put in the extra effort of using the stairs.

The creation of an accessible environment is essential for the academic success of students with disabilities. A closure of the Murchison elevator would mean that disabled students would have to transport themselves all the way around campus near Storch Memorial. This extended walk could impact lower-campus students with heart conditions, as they could potentially be subject to a heart episode or irregular heartbeats. Students using mobility scooters or wheelchairs face an increased risk of falling over due to cracks in the pavement, while also having to consider the additional time it takes to get to class.

As a former Murchison Hall resident, I was frequently disappointed with the fragility of the Murchison elevator. Upon being lifted to upper campus, the elevator would always jitter as though the cords were going to snap at any moment. The elevator would often be in need of repair, forcing me and any student with muscular dystrophy to use the stairs — or worse, the infamous Cardiac Hill.

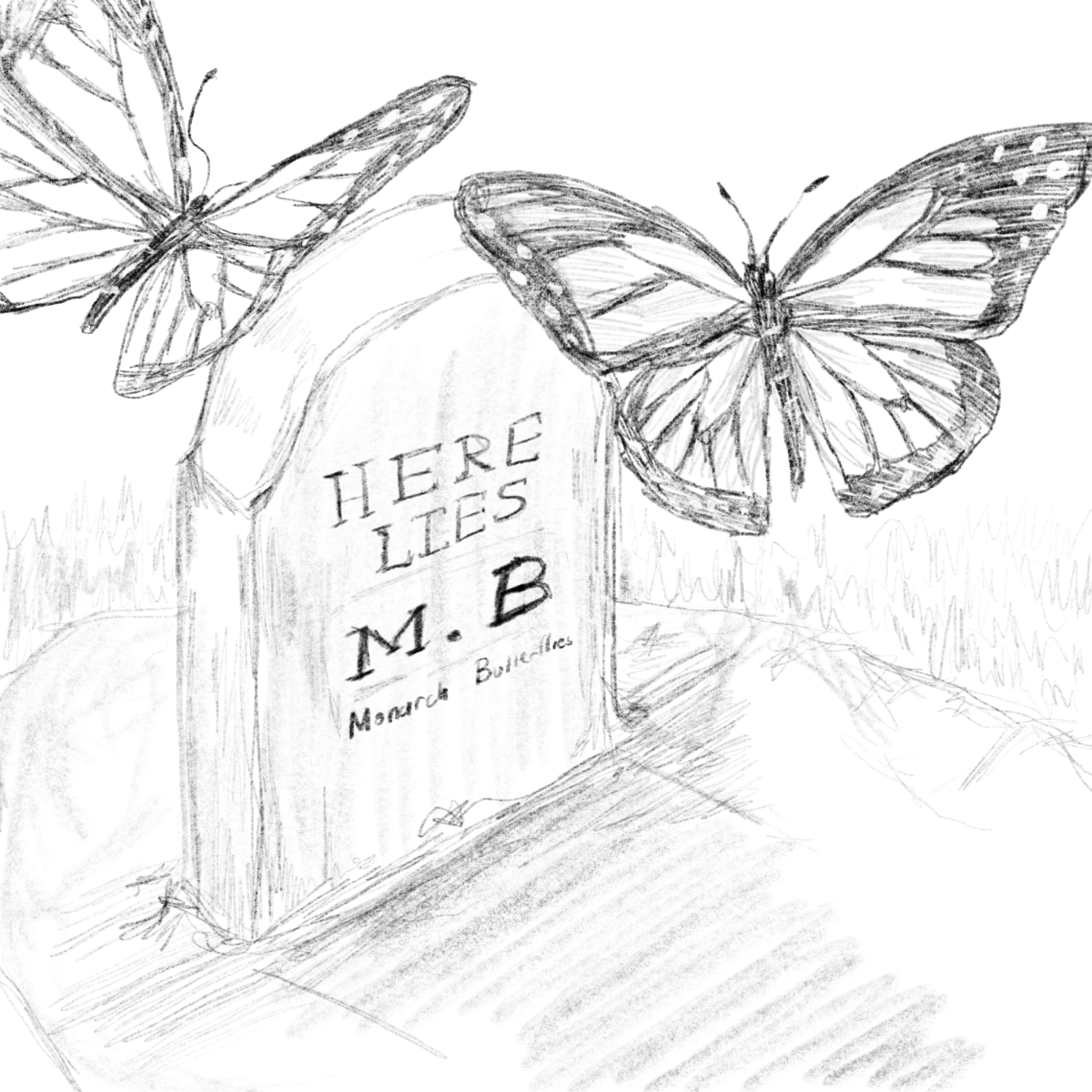

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act Title III regulations, private entities must adhere to guidelines that ensure that an accessible path of travel is available when areas are under construction. Yet, loopholes are created through the use of overly broad language, such as “maximum extent feasible.” The policy also includes an exception in cases where “the cost and scope” of a temporary accessible pathway is deemed as too big of an expenditure. These policies meant to protect disabled individuals don’t provide enough clarity to ensure appropriate accommodations.

The only real way to solve the issue of accessibility on campus at the moment is to organize and work together to enforce change. Examples include but are not limited to, increasing the use of TUPD golf carts on campus, students offering car rides to each other, or advocating for Trinity to invest in an extra accessible route to compensate for any future problems.

It seems that the average able-bodied person is not used to asking themselves if a disabled peer would be able to participate to the same extent as they can. We must strive to extend our hand when we see ourselves in a position of privilege, and ask ourselves the important question: How can I help my peers that are suffering? This is the mindset exemplified by Mike Fabiano, an able-bodied man caught in an unthinkable disaster:

On 9/11/2001, John Abruzzo, a man dependent on his wheelchair, was left stranded on the 69th floor of the North Tower while his peers evacuated down the stairwell. Mike Fabiano, along with co-workers, stopped to help Abruzzo, taking turns carrying him down each stairway on an emergency evacuation chair. They made their escape shortly before the building collapsed.

There may not be a building on fire and on the verge of collapse here on campus, at least not in literal terms. But, do we really have to wait for a dire emergency to realize that the physically disabled are being left behind?