Students are raising concerns over the growing number of red lights on campus water bottle stations. Usually, these red lights signal that the filters inside the stations are in need of replacement, but Trinity University officials insist that the water is safe to drink despite the red lights.

Senator Blaine Martin recently launched a Student Government Association (SGA) initiative to reach out to Ernesto Gonzalez, associate director of Facilities Services. At the same time, I conducted a water testing experiment on most water bottle filter stations on campus to find out our best sources of water.

In the Sept. 26 SGA Senate meeting, Gonzalez issued a statement through an email explaining how the current filtration system lacks the ability to change the filter status lights.

“I know the red light seems to be a red flag, but it is only because the filters we are using do not turn the light off,” Gonzalez wrote.

According to Gonzalez, he found a cheaper alternative to the standard Elkay bottle filters. He also noted that Facilities Services keeps track of filter replacements with an Excel spreadsheet and replaces them at different frequencies.

“Higher traffic areas where bottle fillers would be used more often, [such as] Bell Center, Chapman, Dicke Hall, Library are being replaced quarterly,” Gonzalez wrote. “In the less trafficked areas, we are replacing filters every four to six months.”

President Joy Areola noted that Gonzalez assured her the water is safe to drink and that, while the red/green light system may have no meaning currently, Facilities Services is addressing the issue. The Trinitonian reached out to Facilities Services, but they declined our interview request.

According to Calvin Kirkpatrick, senior history major, the current filtration system creates many areas of concern including water quality, accessibility and even sickness as a result of water consumption.

“Myrtle and Susanna have water fountains that give you the runs,” Kirkpatrick said. “There’s no water fountain on the third floor or second floor which, combined with the fact that there’s no elevators in the entire complex means that [for] people who are mobility impaired like myself … getting water is a preparation.”

In conjunction with Kirkpatrick, the Trinity University chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) is currently working on increasing awareness about water accessibility. Brooklyn King, YDSA organizer, discussed their club’s goals to advocate for clean, accessible water by providing water fountains on all ground levels, maintenance requests for filter replacements and creating publications regarding the impact on students.

“Water fountains aren’t necessarily an issue of accessibility for certain groups of students. It’s a question of accessibility for everybody on campus because everybody deserves the right to clean and accessible water,” King said. “We thought it was a pretty deeply felt issue, and we just wanted to be able to provide some tangible change for students on campus.”

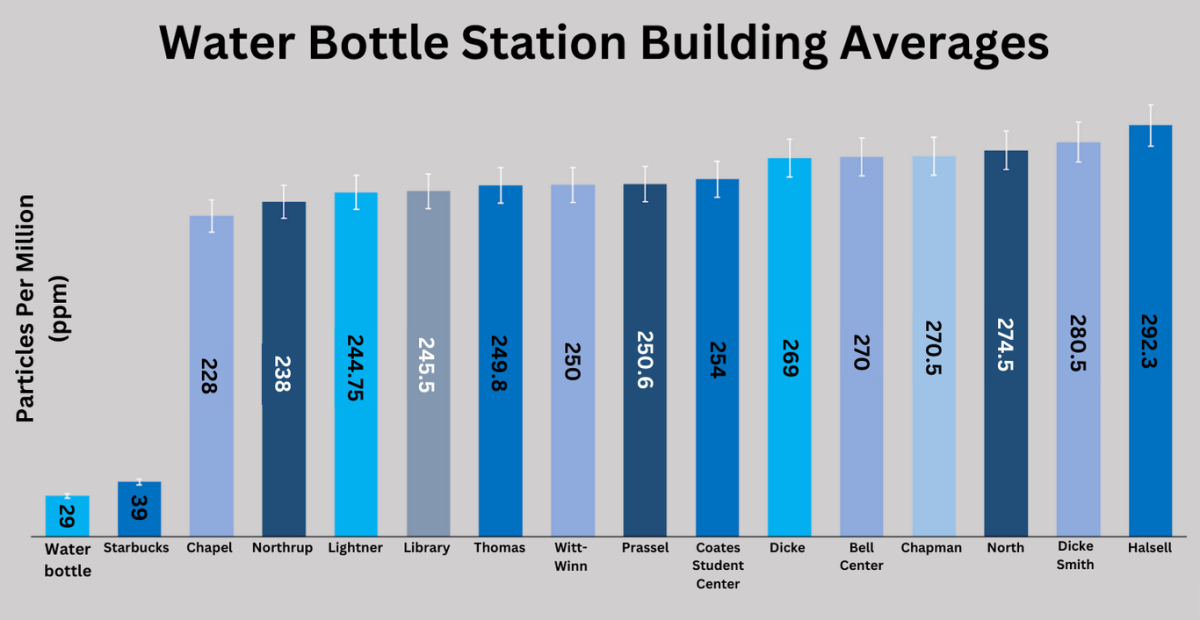

Through a self-led initiative, I tested the water filtration system in almost all buildings on campus and ranked them according to the amount of particles found in the water. Firstly, my results confirmed that the red light, green light systems have no discernible meaning regarding quality. Out of the 36 tested water bottle stations, 18 were either red or had no light indication, yet their displayed status gave no insight into the actual water quality.

Furthermore, there were four broken water bottle stations and seven campus floors without water bottle stations, including both Verna McLean Hall and the Center for Sciences and Innovation without any working water bottle stations in the building.

The measurement used parts per million (ppm) of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) to test the water quality by reporting the amount of particles in a given amount of water. It is important to note that this is not always the most accurate measure of water quality, as the measurement does not distinguish between types of dissolved solids, such as harmful pollutants or minerals. However, TDS is a standardized method for deducing water quality and is used in many professional settings, along with pH and dissolved oxygen.

According to my results, the best locations on campus to get your water bottle filled are the first floor of the Margarite B. Parker Chapel (228 ppm) and the third floor Northrup (220 ppm). The most TDS were found in Ewing Halsell Center floor three (303 ppm), Ewing Halsell Center floor two (293 ppm) and North Hall third floor (292 ppm). For a more detailed list, see the graphic on building averages above.

Overall, the water filtration system is very similar across campus, with all water bottle locations ranging from 220 ppm to 303 ppm, averaging about 260 ppm. To put this in perspective, the ideal drinking water for distillation or reverse osmosis is said to be about 0-50 ppm. As stated by the HoneForest TDS meter, the range from 20-400 ppm is “marginally accepted average tap water,” with 300-500 ppm containing “unpleasant levels from tap water.”

The best free source of water on campus would be the Starbucks water with 39 ppm. Secondly, although less likely to be free, water bottles contain a small ppm due to high regulation.

The data is likely to fluctuate as the filters get changed or used more frequently. While it is recommended to be aware of the quality of water, the most important factor is staying hydrated.