At the very first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929, a mere 17% of the nominees were women. Nearly a century later, at the 97th Academy Awards ceremony on March 2 of this year, you’d expect that percentage to have increased. It did, technically, by a meager 10%, but the total percentage of women nominated across the entire history of the Oscars, remains, still, at 17%.

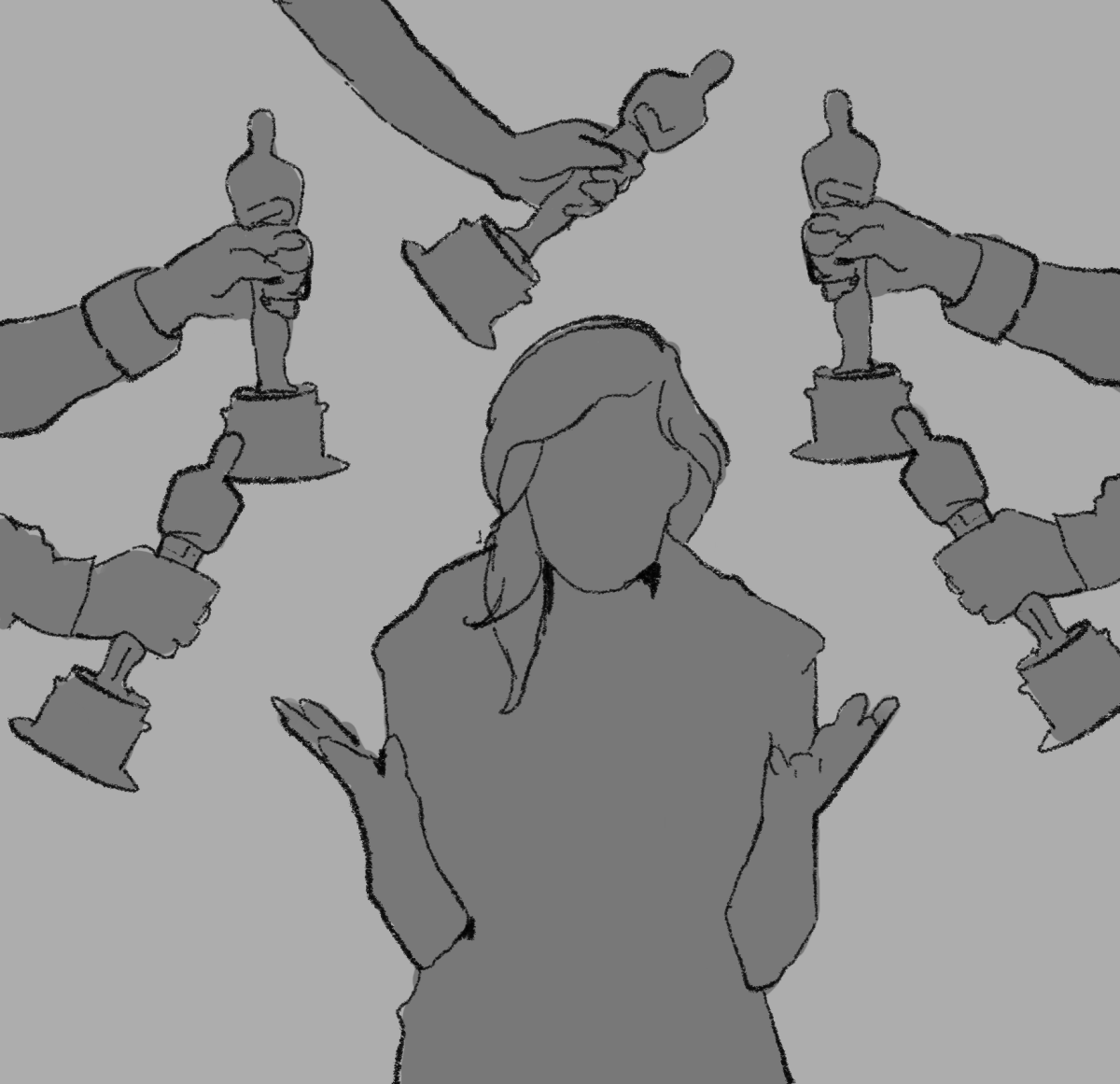

The starkness of this disproportion might be surprising. Much of public attention on the Oscars is centered on the performance categories, which, being gendered, present an illusion of balance. Look beyond that, though, and the illusion is quickly shattered. Cinematography, sound, screenwriting and so many categories have a distinct lack of diversity. Coralie Fargeat, for instance, director of “The Substance,” was the only woman nominated in the Best Director category. Only eight other women have ever been nominated for the award.

This is not an Oscars-exclusive problem, but rather one that plagues Hollywood as a whole. Off-screen, film is and always has been an extremely male-dominated industry. Out of the 50 highest-grossing films domestically in 2024, only four were directed by women, and of those four, two were co-directed by men. The broader underrepresentation of women in prominent Hollywood positions certainly contributes to the nomination imbalance, but it is still not an excuse. The Oscars claim to be a recognition of “excellence in cinematic achievements,” but as it stands, a recognition of “men’s excellence in cinematic achievements” may be a more apt description.

Though the Academy seeks to present itself as committed to highlighting a diverse range of voices, their actions continually prove it to be largely a facade. Take, for instance, the controversial “Emilia Perez,” which was nominated for 13 awards, making it the most nominated film at the ceremony. The film is set in Mexico and features a trans woman as the protagonist, but of the 16 individual crew members nominated, 12 were men and all were white, French and cisgender — not to mention that the film has received significant criticism from the groups it claims to represent.

The Academy’s continual failure to promote meaningful representation on and off-screen makes it clear that they do not wish to inspire any real change within the industry. At worst, the Academy is actively denying women nominations, and at best, they are simply unwilling to seek out a more diverse range of films. Either way, the message sent by the Academy’s long history of nominating men over women is that men’s perspectives and voices are more deserving of recognition than women’s — a message that only serves to reinforce the unbalanced status quo.

Unfortunately, 2025 isn’t looking like the year that things begin to change in the film industry. Until Hollywood begins to truly make space for underrepresented voices, that 17% isn’t going to budge. Yes, the graphs tracking representation in the industry and the Academy nominees over the years may have a positive slope, but 97 years is far too long a time to see such a minimal increase. At the rate it’s going, it’ll be another century before we begin to see things even out. Let’s hope it doesn’t take that long.