Does this scenario sound familiar? You come back from summer break with your bags full and ready to move in, but when you reach your dorm you see orange netting and signage everywhere. Rebar and dirt piles cover the paths you once walked to class. Cars can no longer enter half the parking lots.

Construction has become an annual battle on Trinity’s campus. Students, staff and faculty all struggle to navigate the myriad of obstacles that construction brings. Construction on Trinity’s campus takes two primary forms: new buildings and renovations. While new buildings can serve a valuable purpose, such as providing a home for Trinity’s substantial English department, renovations improve student experiences far more. While both are important, Trinity has rightly prioritized renovations and should continue to do so.

Renovations on older buildings come with less upheaval. Faculty need not vacate offices and students need not learn new footpaths. One could argue that renovations can cause building closures, but through renovations the long-term usability of a building skyrockets. If well-timed, such as during the summer for larger renovations or during week-long breaks for smaller ones, refurbishments on older buildings might avoid interrupting normal use altogether.

By adding buildings, Trinity also reveals its priorities. If the school makes new building after new building, buying up new land, demolishing old areas and neglecting more decrepit buildings like Albert Herff-Beze, Harold D. Herndon and the Ruth-Taylor Theatre building, Trinity shows that it cares more about flashy shows of wealth than the needs of its students and departments.

Renovating old buildings like the school did with Bruce Thomas Hall shows that Trinity cares about the experiences of its existing students. Thomas was once by far the worst sophomore dorm. Now, despite its distance from upper campus, many consider it the best thanks to its new coat of paint and room layouts. Such an improvement has totally shifted the experience of being in sophomore dorms. Where once half the sophomore class would get stuck in an uncomfortable, moldy ruin, now all sophomores get a dorm with decent facilities and quality of life.

In addition, new buildings stack many extra expenses onto basic construction costs which renovations do not. In the best case scenario for a renovation, Trinity would only need to repaint surfaces and patch holes. However, most renovations require more than this. Many buildings need improvements to infrastructure like water pipes and electrical cables. Some buildings might need the removal of hazardous materials like mold or pests like rats and insects. Even so, these renovations tend to cost the university much less than new buildings for very simple reasons. New buildings require new foundations, new basic skeletons and new architecture, all of which cost leagues more than any sort of renovations.

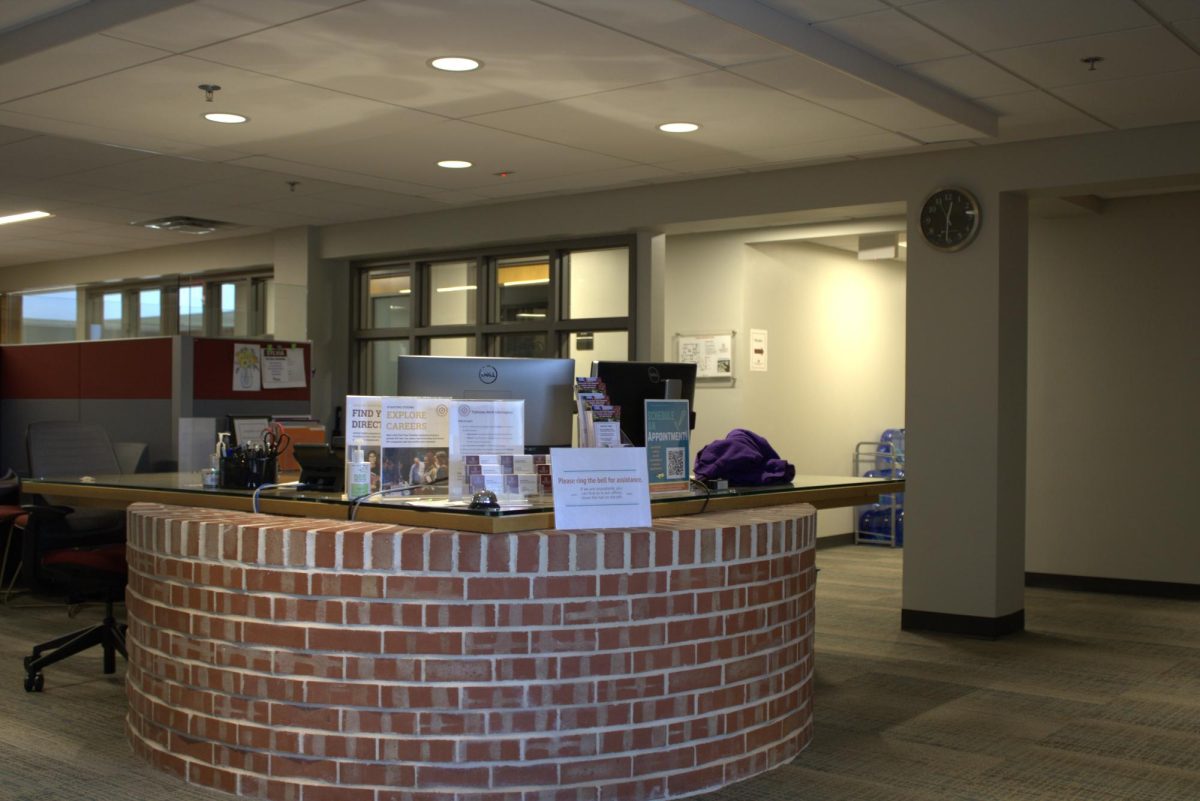

However, renovations do not keep Trinity from periodically needing new buildings. Every once in a while a building can become too damaged to use, requiring demolition and replacement with something new. Even so, by upkeeping our existing buildings more regularly, we prevent them from reaching that state in the first place. Still, Trinity may run out of space in existing buildings as the university grows. In such cases, new buildings would be necessary, but Trinity does not really face that problem at the moment. Ill-conceived policies, such as the maligned three-year residency policy, cause Trinity’s buildings to fill up too quickly, not a lack of space. The current problem with space that we do face comes from Trinity’s habit of inconvenient building and walkways closures such as during the Coates Esplanade or Chapman renovations.

The sheer facts of construction stare Trinity dead in the face; it costs time, loads of money and great deals of inconvenience to build things on a university campus — or anywhere for that matter. Prioritizing renovations helps stave off some of those problems, since they take less time, cost less and can be accomplished in less intrusive ways.

Trinity seems to have the right idea when it comes to construction. Out of the university’s last five major construction projects — the Welcome Center, Coates Esplanade renovations, Thomas renovations, Chapman renovations and Dicke Hall — only two were new buildings. This ratio seems close to right, but things could easily slip out of control. One could imagine new buildings popping up in every nook of campus. Vigilance against unnecessary construction must remain if we want Trinity to keep its culture while also seeing to the needs of its students. So I say: “Vive la renovation!”