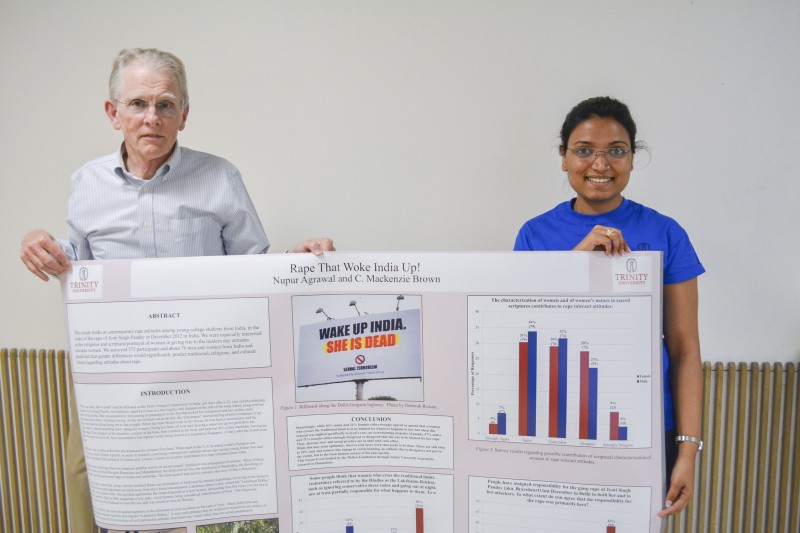

Earlier last month, senior Trinity student Nupur Agrawal and C. Mackenzie Brown, professor of religion, presented their research on rape attitudes in India at the American Academy of Religions in Dallas, Texas, on March 9.

Agrawal spent last summer handing out surveys and interviewing college-aged men and women at several universities around India about their views on rape. Questions gauged students’ opinions on various contexts and situations in which rape happens.

“One of the questions we asked was if rape could result in pregnancy. That question was inspired by Todd Adkins’ comment in the U.S. I was surprised that over 30 percent of Indian women said that rape cannot result in pregnancy. If this were a more general population, I could’ve come to terms with it, but this was a college-going population,” Agrawal said.

Men were around two times more likely than women to realize that rape can result in pregnancy.

“I think thats because the men are simply more worldly and the women are very sheltered and sex is not really discussed with them,” Brown said.

Other questions with responses that stood out to the team included a question asking if marital rape was possible and if women enjoyed being raped.

“Very few women, around five or six perecent agreed with that, but with men, somewhere around 15 percent thought that women enjoyed being raped. With the issue of marital rape being possible, around 33% of women thought that it was not possible. If that seems really outmoded, in 1973 in this country, marital rape was not a crime,” Brown said.

Brown was in Delhi, India in December, 2012 when protests in reaction to the rape and death of Joyti Singh Pandey erupted across the country. Being present during the nationwide unrest and his research in Hinduism inspired him to inquire about the ways people in India perceive rape.

“I think the women’s movement, social media, the brutality, that it happened in the capital city, that it made it’s way into international headlines has really made this much more of a wake-up call. I began to wonder, what is the portrayal of women in scripture and so forth that leads to rape-tolerant attitudes? Were these still persistent themes?” Brown said.

After coming back to the states, Brown asked Agrawal if she’d be interested in being a part of this research project.

“He asked me if I would want to assist him in looking at rape attitudes among men and women. I know four Indian languages and am fluent in written and spoken languages, and being a woman, it also made sense. I could not give up an opportunity like that,” Agrawal said.

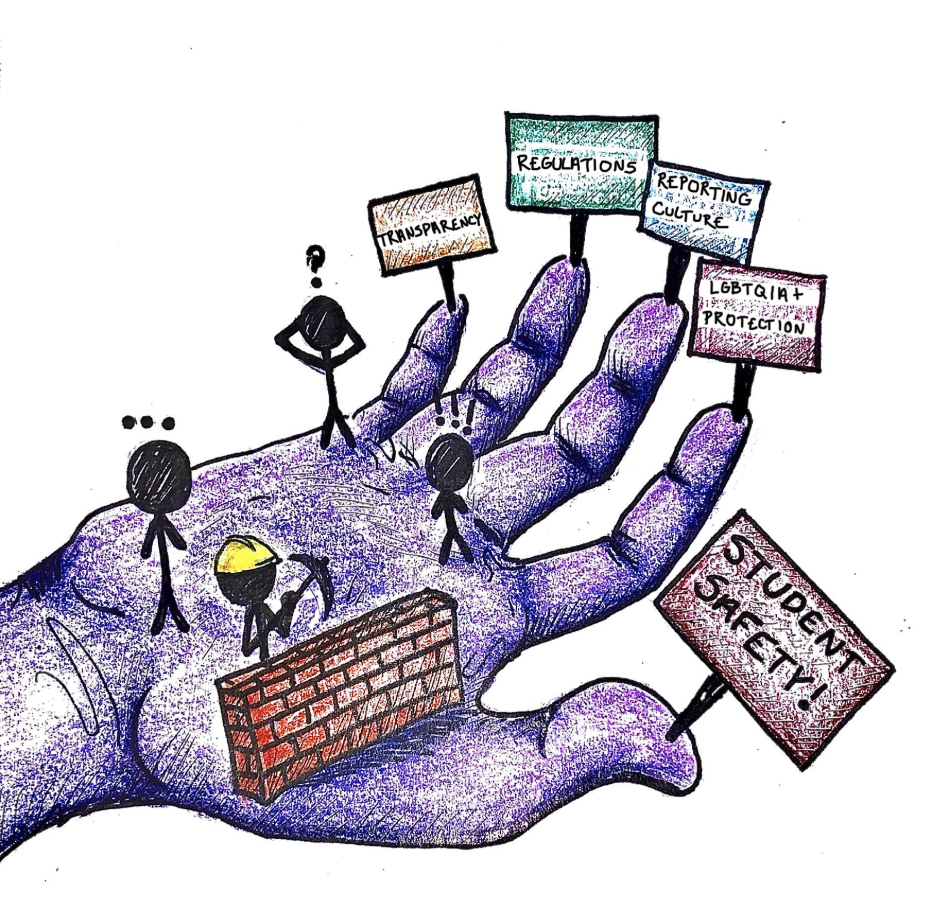

This past fall, Agrawal peer-tutored the class “Rape in India, Rape in America, and Rape at Trinity” taught by Brown. The class looked at the differences in the contexts that rape occurs and the pressures that survivors face in these different places.

“I think there are some huge differences. At Trinity and on American campuses overall, date rape is by far the most common setting in which this occurs. You don’t frequently have these brutal rapes,” Agrawal said. “It’s very different from the Indian context, where rapes typically don’t involve alcohol and domestic abuse is more common.”

The class consisted of 13 first-year female students. Despite initial apprehension, both Brown and Agrawal found the class to be enriching and worthwhile.

“Being a peer tutor for the class gave me hope because these were women who were there for some reason that they wanted to change. They wanted to be empowered: to do something,” Agrawal said. “They thought something was wrong and they wanted to have the skills set and be more informed. I didn’t know what stories they were going to bring or if they had a history or if they knew somebody. I have never had a peer tutor-experience that can match that.”