September 5 was the already-delayed date for Trump to announce his plans for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. The DACA program allows “˜Dreamers’ to apply for work permits, study in school and be protected from deportation. I couldn’t imagine what it must be like to watch DACA end for the 800,000 undocumented immigrants and their families … so I sought out someone who would explain it to me.

Born in San Luis Potosi, his parents brought him across the border when he was two years old. He drives a modest car an hour each way on his commute to work, where he manages a retail store. Growing up alongside American-born children, he watched cartoons like “Spongebob,” “Hey Arnold.” His favorite? “The Wild Thornberries “¦ because I always wanted to travel, but I never could.” Because of his status, driving down the road was a risk, much less a trip abroad. My source has no recollection of ever being in Mexico, yet now faces the prospect of going ‘home.’ “Getting thrown into to a country where I really have never been “¦ where am I gonna go? I have no idea,” he said.

His earliest memory was in Wisconsin, where his parents worked on a potato farm. “They pay you nothing. You are forced to be there for 12 hours a day. You don’t get overtime. There’s no benefits, no nothing. And then you still have to find time to take your child and get him registered for school,” he said. “My sister, at nine years old, was cooking and cleaning, taking care of us.” But to struggle in this country was more preferable than remaining in Mexico.

“I don’t know where people get these insane ideas, that “˜they want to come here and get free things’ “” no, we don’t,” my source said. “Even with Obamacare, we have to pay the fee for it knowing that we don’t qualify for those insurance programs. Luckily, we didn’t get sick much.” It begs the question, what do immigrants actually get from being in America with DACA?

“We don’t get the benefit of federal student aid,” he said. “I worked my ass off my entire life to be successful “¦ I graduated with zero college debt, working and going to school.” College for him was lots of work, and very little sleep. So little that during an exam, he couldn’t stay awake while sitting at his desk; rather than give up, he asked the professor if he could take the test standing up. If there is any stereotype that fit this Mexican, it’s that he’s a hard worker. “Every single thing that I own I got from my own blood, sweat and tears,” he said.

Yet, there are those who believe that the best thing for this country would be to deport people like him.

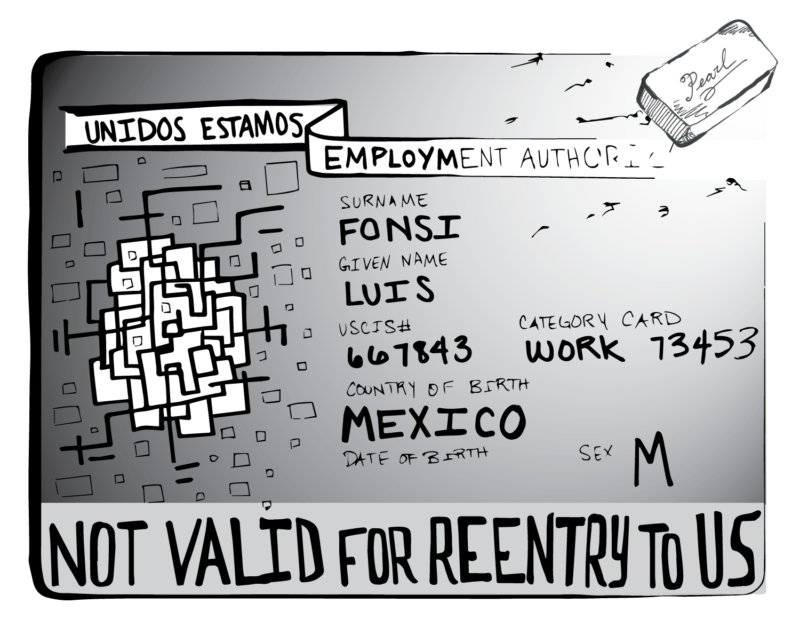

“We provide jobs “¦ we don’t mooch off of anybody “¦ and we have to pay for [DACA]; it’s basically a self-funded program,” he said. “Every day I have to listen to them tell me all the reasons why I need to get out of here, and I bite my tongue every time,” he said. “But at the same time, the people who are against this program “¦ Where do they live? Do they associate with people like us? “¦ Most of the time, it’s people who haven’t been exposed to people who have DACA “¦ I don’t hold anything personally against them.” Now, he is scared that becoming a part of the program will come back to haunt him. “They have all my information that I gave them; my address, my work “¦ that’s where my parents live,” he said. Why does he believe he should be here? A long pause. Then, he says “I was ready to give my life for this place “¦ this place is my life. People who line up to serve in your military “¦ they’re dying to serve other Americans,” he said. As we moved to leave, I asked him if I could take a photo of the ID that will soon mean nothing. I wanted you, my readers, to know what it looked like. He paused and said, “How about you just tell them what it says? “˜Not valid for re-entry to the US.'”