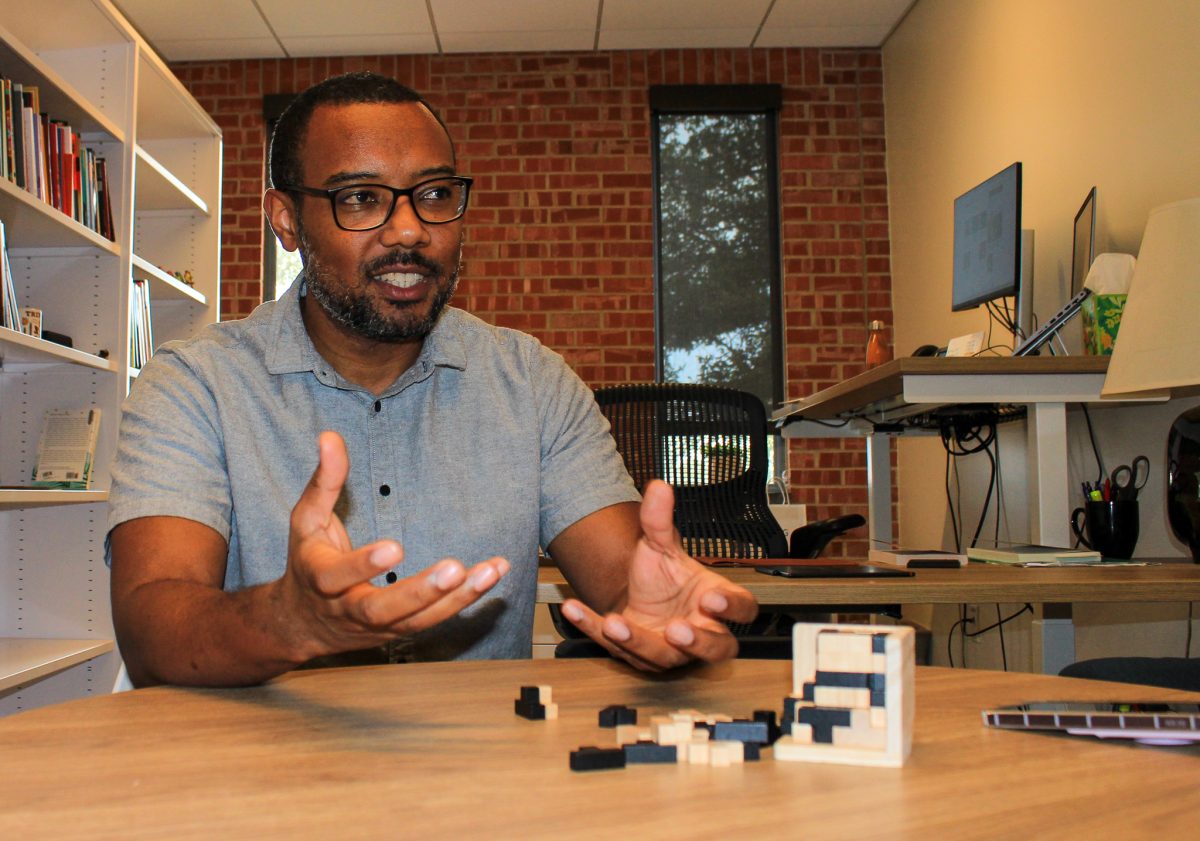

Richard Reed, director of the environmental studies department, is on sabbatical this semester. Trinity faculty members are given sabbatical leave for the purpose of encouraging them to engage in research in their fields or other activities that relate to their fields of scholarly interest. Reed is taking the semester to work in the field, literally: he is spending portions of the semester at his family farm in Wisconsin, and when he is in San Antonio, he is fostering hives of bees.

“As director of environmental studies, I have a couple of different things going on. As a professor, you study and think about your subject all the time, but that’s different than actually doing it. Putting it into action is different than writing and analyzing, so I’m doing a bit of both this semester,” Reed said.

Reed’s family has had a farm called Basswood Hill since 1886, when they homesteaded a section of land in northern Wisconsin. Growing up, Reed visited the farm for vacations; however, he never really experienced the farming part of Basswood Hill. During spring semester of 2012, Reed thought that it would be an interesting experiment to actually try to run the farm himself, while being especially conscious of environmentally friendly practices.

“My family used to work this farm””wouldn’t it be fun to actually do it? In an environmentally friendly way? After classes ended last spring semester and before graduation, I went up to Wisconsin to plant a garden of organically raised heritage vegetables with seeds from Iowa. My brother-in-law, my son and I plowed and planted the produce,” Reed said.

The three of them spent the rest of summer 2012 engaged in organic garden production and cattle management. Reed sees the summer of 2012 as an experience in which he put his field of scholarly study into action. During that summer, Reed started his own project in addition to produce farming and cattle raising: beekeeping.

“Bees were basically my project. I started with bees here in San Antonio. The winter before going up to the farm, I contacted the Alamo Beekeepers Association and got on a list that basically facilitates bee collection,” Reed said. “When someone calls complaining of bees on a fence, or in a chimney, we go up and capture the bees, or the swarm.”

In a single swarm, there can be around 30,000 bees, and one of the bees is the queen. The queen of the swarm is the central focal point of the entire hive.

“She’s the most important because everyone organizes around her. If you can get the queen, all the rest of the bees will follow. The thing about bees is that they aren’t really domesticated””they’re wild. All you can do is create an environment that they want to live in and hope that they stay with you,” Reed said.

By the time summer 2012 came around, Reed had collected a lot of bees, which resulted in a lot of honey, but had not had success maintaining a hive.

Environmental studies and art double major Allison Skopec appreciates Reed’s willingness to venture out of the classroom to enrich his knowledge of environmental studies and relate that knowledge to other scholarly fields. She also does beekeeping in Seguin and is aware of the amount of effort necessary but also the excitement that comes from the process.

“I have been interested in bees and beekeeping ever since I first saw an episode of Magic School Bus where the class journeys into a beehive and the gang learns about the intricacies of bee social hierarchy. In January, I started beekeeping in Seguin and it’s been nothing short of fantastic. I think it’s very important that beekeeping grows in popularity because bees are crucial to our survival as humans; we depend on these little guys to pollinate our crops. In fact, bees are responsible for pollinating 80 percent of flowering crops which constitute about one third of the food that we consume,” Skopec said.

Due to the amount of effort and attention necessary to attain and keep bees, Reed decided to jumpstart the process of successfully keeping a hive.

“I ordered four hives of bees and sent them to Wisconsin, and we got started with the bees up at the farm that summer,” Reed said.

Reed kept the bees all of summer 2012, and then when it began to get cold, he transported the bees himself down to his home in San Antonio.

“I put the bees in my station wagon and drove them down to San Antonio, which probably would’ve made anyone who wanted to pull me over nervous, because there was this swarm of bees confined by a mosquito net taking up the majority of the back of the car,” Reed said.

Skopec, who has taken classes with Reed before, respects his enthusiasm.

“One of Dr. Reed’s most admirable qualities is his enthusiasm to whole-heartedly inject himself into whatever new project he is taking on. Beyond being extremely well-read in the nuances of beekeeping, he’s actually starting to take care of his own hives. This is no small feat and he learned firsthand how difficult it can be to start out””bees can spontaneously swarm if they’re unhappy with their location, there is a daily risk of being stung, and bees are very susceptible to disease, including mites,” Skopec said.

Reed integrates his three primary fields of study””environmental studies, anthropology and sociology””into his work with the farm and with the bees. Reed observes the bees both from an environmental studies perspective and from an anthropological perspective, and assesses what bees mean in the context of greater society.

“Dr. Reed has been taking time to learn about the ins and outs of organic farming and what it takes to make a sustainable business model work. When Dr. Reed comes back to Trinity, he will be able to incorporate his time on the farm into constructive and interesting dialogue with students. His teaching style is very accessible in the sense that academics are always supplemented with tangible knowledge,” Skopec said.

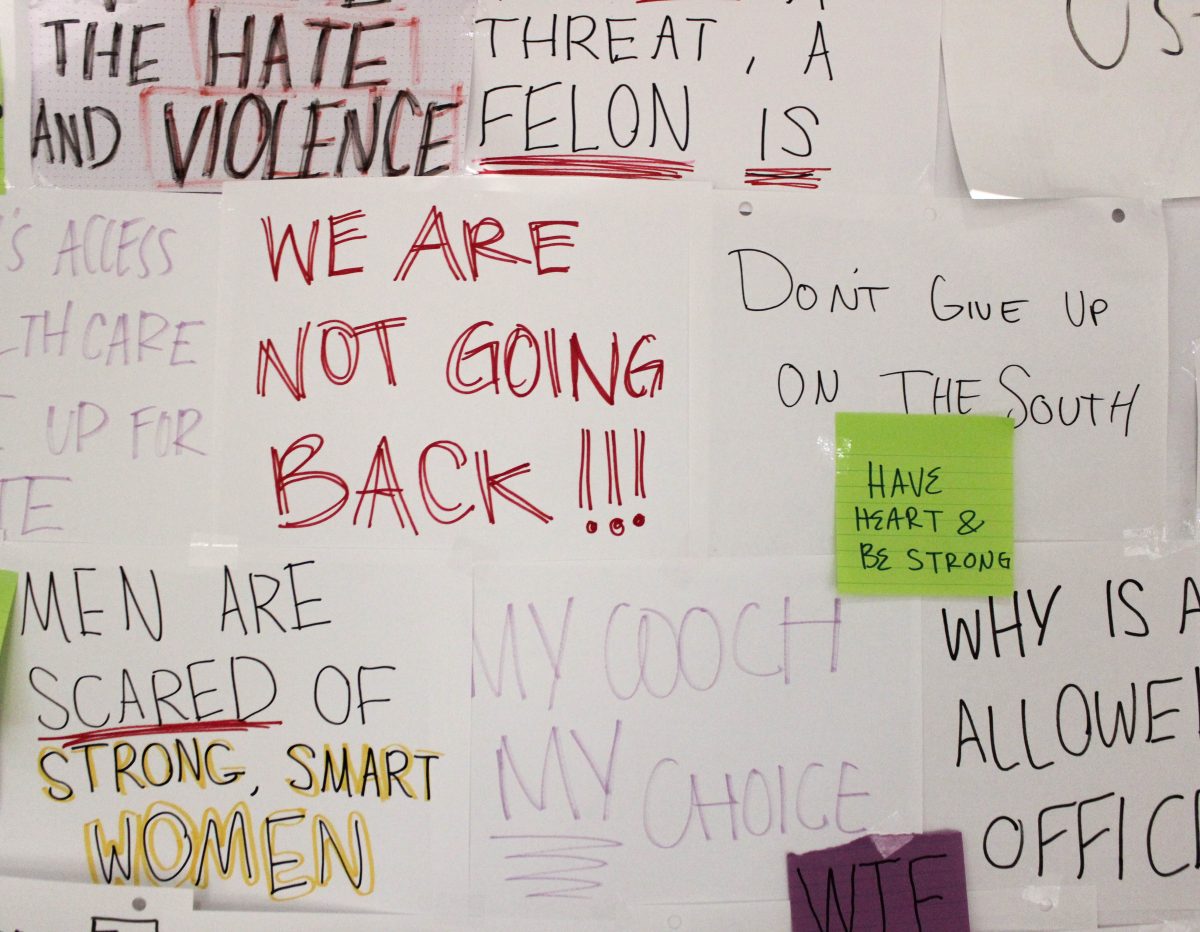

According to Skopec, there is already an existing trend toward eco-friendly farming on campus.

“There is a rising interest in the student body in organic and sustainable farming, especially seen through the Trinity community garden, and Dr. Reed will be able to help advise students who want to start their own garden, whether professional or personal, on gardening techniques and practices,” Skopec said.

To unify the concepts of studying and engaging with his field of study, he is also writing about the landscape history of the past 200 years of the plot of land in northern Wisconsin on which his farm is located. This analysis includes a discussion of the demise of farming in the United States. He finds that there is a basic need to reorganize the way our society “does things.”

“In terms of energy, and the effects of the energy we use, we need to consciously think through how we do things. We need to constantly be aware of the change in our relationship with the environment””we shouldn’t be afraid, we should just be aware and accepting of the changes we’re going to have to live through,” Reed said.

In these writings, Reed uses a different voice than that of a traditional academic.

“It’s not that of a scientist, and not an anthropologist””it’s a different way of looking and understanding,” Reed said.

“There are bison bones on the farm, which goes back to the indigenous people who settled there long before anyone else. I’m also going back to the first settlers, my family, and moving forward to the present and analyzing the relationship of people who have lived there and farming, and their relationship with the land itself,” Reed said.

Senior Mitch Hagney, a double major in international environmental studies and human communication, recognizes the value of a professor who follows his or her passions outside of the university setting.

“We all want to get our hands dirty in environmental studies, but we’re not usually sure where to start. Courses like environmental ethics pose theoretical choices that are intended to challenge students. Dr. Reed now provides actual choices from his experience that he can force students to fully explore””professors are best when they are passionate. His experience has brought out the best in him, which will bring out the best in his students,” Hagney said.

On Thursday, March 21, Reed began a trip back to Wisconsin for maple syrup season, and he plans to stay there for a while before coming back down for end-of-semester activities and graduation. Afterward, he plans to take the bees back to Wisconsin.

“I don’t think I’ll try to do the farming this summer””I’m not meant to be the farmer as much as the anthropologist, and that’s okay,” Reed said. “Last year, we did everything””we sold to farmers’ markets, marketed beef locally, and those experiences shifted the way I think about farming and agriculture,” Reed said.