As I scroll through my Twitter feed, retweeting Bernie Sanders’ passionate calls for health to be declared a human right, it’s easy for me to forget that most of the political opinions that appear there are only shared by a fraction of our country’s population. In fact, if Twitter and Facebook were my only sources of news and current events, I might believe that the entire world subscribed to a mostly liberal political stance such as mine.

In reality, I know that around 46 percent of our country voted for a president who represents ideologies to which I am diametrically opposed to. So why does it appear, through the lens of social media, that everyone agrees with most of my political viewpoints?

The very nature of social media is focused around giving you more of what you like. Even a quick look into your Facebook ad preferences will show you what Facebook has determined is your political affiliation. (Somewhat surprisingly to me, it labels me as “moderate”).

If Facebook shows you more of the types of ads and posts that bring you pleasure, you’re more likely to keep using Facebook. As a business model, this makes a fair amount of sense: give the people what they want. However, this can pose significant challenges to a productive political discourse.

If people become accustomed to the idea that the world is on their side politically, it becomes easier for them to demonize and reject any opinion that doesn’t line up with their own. While it is perfectly within your right to vehemently disagree with an opinion, a lack of information about what the other side is saying leads to gross misconceptions that ultimately lower the degree to which you can debate effectively with an opponent.

However, not all the blame can be placed on social media like Facebook; we are the willing participants in the confirmation of our own biases. A University of Pennsylvania study examined media consumption on Facebook, keeping track of the proportion of “cross-cutting” (i.e. different from the user’s opinion) content shown to users from both liberal and conservative backgrounds.

Although Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm was influential in reducing the proportion of cross-cutting content that users saw, the proportion of that content that users actually clicked on was even smaller. This means that we, as users, are responsible for neglecting to hear the other side of the political spectrum.

Additionally, news outlets themselves need to be wary of practices that lend themselves to partisan viewing only. As a Washington Post article stated, outlets should “resist pandering to established constituencies, despite the temptations of a guaranteed audience and trend-driven traffic,” citing a headline by the Associated Press that referred to Ruth Bader Ginsburg as “the Notorious RBG,” a popular term among younger and more liberal voters.

If articles start taking a partisan lean just from the headline, Facebook algorithms will likely latch on to it and distribute it among those who already agree with that source’s opinions.

Fortunately, a small amount of research can go a long way in helping to understand the argument of the other side. The Wall Street Journal’s “Blue Feed, Red Feed” displays side-by-side the two different partisan interpretations of similar news events, sorted by categories such as “Health Care” or “Guns.”

Alternatively, Steven Crowder’s Youtube series “Change My Mind” provides a more personal debate as Crowder invites random people from the public to convince him that his (very conservative) views are misguided.

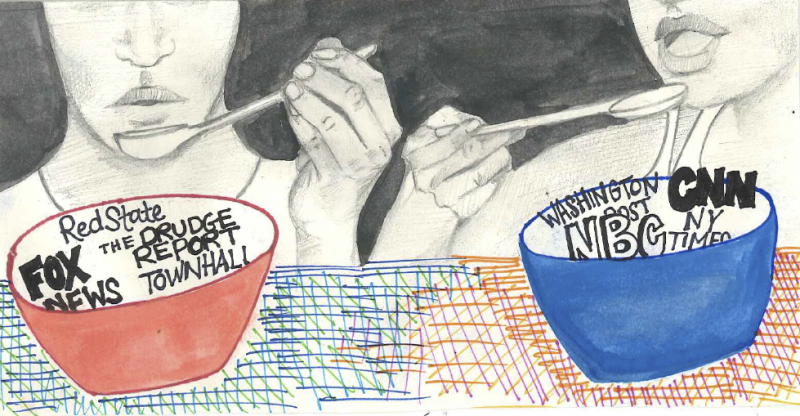

Both of these examples provide ways to escape the “echo chamber” of social media that often arises when algorithms and biases trap us in a redundant feed of the same opinions. As satisfying as it is to keep retweeting those liberal or conservative political memes, I recommend expanding the aperture through which you consume the news as it relates to politics.

Every story can have a spin, and oftentimes examining how a story is spun the other way can help you better understand your own stance. Whether it changes your mind or not, a diverse political consumption of media is healthy for both your own opinions and for our society’s discourse as a whole.