A team of 15 faculty and staff has been assembled to lead the development of Trinity’s Quality Enhancement Plan (Q.E.P.), which will focus on enhancing first-year students’ learning through strategic changes to teaching, advising and support services.

The Q.E.P. is a part of Trinity’s reaffirmation of accreditation, which is required every ten years to maintain our status as an accredited institution.

“They had a number of open forums and ideas workshops for people to come together and talk about areas that they thought might be good for a Quality Enhancement Plan,” said Diane Saphire, Associate Vice President for Institutional Research and Director of Institutional Research. “Out of that process there were a number of proposals that came forward, there was a number of rounds of vetting events and presentations to the whole campus.”

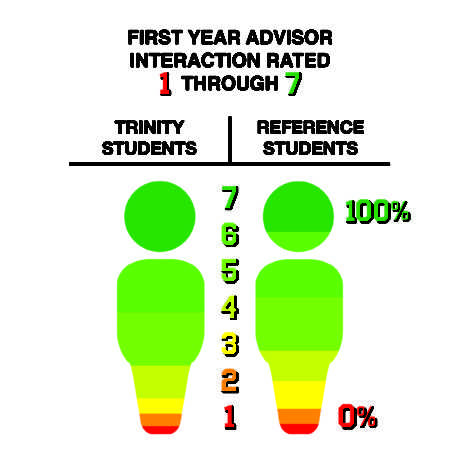

The selection of the “Starting Strong” proposal was driven in part by institutional research, which showed that Trinity lags behind peer institutions in first-year advising.

“On a lot of these questions, these questions like how many times you and your adviser discussed academic interests, course selection, academic performance “” it’s not that we look terrible, it’s that almost every question we lag that group just a little bit,” Saphire said.

Additionally, institutional research has shown that in 2015, almost a third of Trinity first years had a deficient grade (D+ and below) during their first year, and 43 percent of these deficient grades were F’s.

“I think all of those things together… made a compelling argument to faculty members that this is an area that we could do better in,” Saphire said.

After a careful evaluation process, president Anderson, the executive staff, and a selection team chose the Q.E.P. proposal that will be developed this year. The selected topic has the working title, “Starting Strong: Intentional Strategies for Improving Student Success at Trinity University.”

“Everything about our proposal is intentional,” said John Hermann, associate professor of political science and chair of the Q.E.P. “We call it “˜intentional’ because we’re going to be strategic in how we help the students. We realize one size does not fit all.”

Hermann, who was a leader of the “Starting Strong” Q.E.P. from the proposal stage, expressed the importance of broad-based campus involvement in the development process.

“The proposal had suggested strategies for how we might address each of these things, but it really is not a plan,” Hermann said.

He explained that the proposal is simply a topic with justification for why we as a campus should address it, along with some suggested strategies.

Most of the 15 members of the Q.E.P. team will sit on one or more of three subcommittees: advising, chaired by Diane Persellin; teaching, co-chaired by Victoria Aarons and Lisa Jasinsky; and support services, chaired by Alex Gallin-Parisi.

These subcommittees will include faculty, staff and students. They will develop plans for how to create measurable improvements in each of the areas covered by the subcommittees.

“We’re getting a lot of faculty interest in signing up for all three committees, so that’s really exciting, said Diane Persellin, professor of music education and chair of the advising committee. “I think the excitement will be there, I think it will be shared with faculty and chairs of departments.”

The subcommittees will present their plans at open forums where all faculty, staff and students are encouraged to share their opinions. The team will write up a final plan based on campus-wide input through the subcommittees and open forums.

Throughout the proposal stage, a number of ideas have been explored as possible means of attaining the goals of the Q.E.P.

In teaching, for example, the Q.E.P will explore early-alert systems that provide low-stakes assignments that let students know how they are doing early in the semester.

“By midterms, sometimes it’s getting late,” Persellin said. “If we know by the third or fourth week, it’s like, I can get tutoring, I can go to the student success center, I can talk to my adviser about getting other resources.”

Ideas like this are likely to shift and change throughout the development phase. James Shinkle, professor of biology and member of the teaching committee, explained the importance of flexibility in the development stage.

“The reality is that the Q.E.P did have a fairly ambitious set of objectives, and adhering to the letter of those objectives may not be the way to get to the spirit of the overall outcome,” Shinkle said. “If we start by asking the question, “˜What needs to happen?’ rather than immediately saying “˜Well, we’re going to make it happen this way,’ I think we’re more likely to get to a feasible solution.”

The completed Q.E.P will be vetted by the Southern Association of Colleges Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC).

“They’re going to go and investigate the scene and make sure that the administration was not exclusively behind it, or myself as chair decided to push this proposal,” Hermann said. “They’re going to see that there were broad-based stakeholders that were involved.”

SACSCOC is the regulating body that grants or denies accreditation to colleges in the southern and southeastern parts of the United States.

This accreditation is indispensable to the value of a Trinity degree. It provides legitimacy so that other institutions will accept transfer credits from Trinity, graduate schools will accept Trinity graduates and Trinity students will continue to have access to the $20 million plus in state and federal aid they received last year.

“It’s a big deal to retain our accreditation,” Saphire said. “It’s something that all schools have very high on their priority list because students and the institution seven if they’re private institutions like we are rely on that aid that we get through the state and federal government.”

But the Q.E.P. is valuable to Trinity for reasons beyond accreditation.

“It helps us to ensure that we don’t get stagnant,” said Kathy Friedrich, director of assessment for the program. “It forces us to look at how our students are doing, and is there something that we can be doing better to enhance their experience here.”

The reaffirmation of accreditation process was not always so forward looking. In fact, this is only Trinity’s second Q.E.P.: before the institution’s first Q.E.P. ten years ago, SACSCOC’s reaffirmation process was largely retrospective.

“They would have to write this ten-year report reflecting back on what they had done in the past 10 years,” Saphire said.

This changed fifteen years ago, when SACSCOC changed its process to require a Q.E.P. instead of a retrospective report.

“From my perspective it was just night and day from what we used to do,” Saphire said. “It got people engaged; they were excited about picking a topic, they were excited about the possibilities of doing something to improve student learning, because they that’s what we’re all here for.”

The development process will bring some challenges, specifically limiting the scope of the plan.

“[There] was recognition that the advising side and the student support side really are complementary, and to do one in complete ignorance of the other was probably not going to be the optimal outcome,” Shinkle said. “And then it was just, can we still keep this inside a reasonable sized box? Is there still a project here or is this just, let’s reinvent the entire university?”

One way to limit the scope of the Q.E.P. will be to focus only on measurable goals.

“Before they finalize what they’re going to do, I can come in and say, “˜OK this is a great idea, but we don’t really have a good way of measuring it’,” Friedrich said. “How might we refine it a little to make sure that it is measurable and something that we can assess?”

She also expressed that limiting the scope of the Q.E.P. does not have to mean abandoning good ideas.

“We want to be sure that if something does come up that doesn’t fit in the scope of what we want to look at, that the administration’s aware of it, and it can be addressed another way,” Friedrich said.

Hermann expressed that there may also be a challenge in balancing responsiveness to suggestions from the Trinity community with adherence to “best practices” according to the literature regarding programs focused at first-year students.

Finally, Shinkle and Friedrich identified consensus as a potential challenge.

“Getting people to a common understanding of how what they already do and what they already believe in fits,” said Shinkle, “and then on top of that the commitment to say, OK, there is a place I still have to change a little “” getting them to buy in and say, I can do that.”

The subcommittees are currently looking for student input.

“Students view things very differently than we do as faculty,” Hermann said. “Their experience tells us a lot about how we’re doing.”

While changes will not be broadly implemented until 2018 “” with some pilot programs beginning in the fall of 2017 “” there may be some subtler changes in the meantime.

Students interested in sitting on a subcommittee, submitting a suggestion or learning more about the Q.E.P. are encouraged to contact John Hermann.

Data Provided by Diane Saphire