As Trinity moves forward with the development of the Campus Master Plan, the administration has been seeking designation as a National Historic District. The university’s application was approved by the Texas Historical Commission, a major step in the process of being placed on the National Registrar, according to Sharon Jones Schweitzer, assistant vice president for university communications.

The news was announced in a campus-wide email from Danny Anderson, president of the university, on Jan. 22.

“I am pleased to announce that our application to designate Trinity University a National Historic District was approved this weekend by the Texas Historical Commission,” Anderson wrote. “The next step is for the Commission to forward our application, along with its approval, to the National Park Service. … This state-level approval marks a major milestone in our journey toward National Historic District designation for our campus.”

According to Schweitzer, the application will now be sent to the National Parks Service before the final designation is granted in mid-June.

Gordon Bohmfalk, director of Campus Planning and Sustainability, described the role of the Texas Historic Commission in the process.

“It’s a federal program. The idea is it recognizes historic places in history. There are several different categories, architecture being one of them, and so it is something that encourages both preservation and reuse of buildings so that they’re not destroyed over time,” Bohmfalk said. “It’s a program to encourage maintaining those buildings and design ideas for the future.”

Because the Campus Master Plan is designed to layout an architectural plan for Trinity, members of its committee, led by Diane Graves, former assistant vice president for academic affairs and former university librarian, contributed to this process.

Bohmfalk said because the majority of architect O’Neil Ford’s work is on Trinity’s campus it makes sense for the university to apply to the national registrar as a historic place.

“It actually came out in the process of developing our master plan, and I think that it was of course pretty well ingrained in all of the committee members and our consultants that the work of O’Neil Ford and the Trinity architects, most of his work was done in Texas,” Bohmfalk said.

Katherine O’Rourke, associate professor of art and art history, explains the significance behind receiving such a title.

“I was quite surprised to learn that Trinity was pursuing the designation. Doing so appears to represents a significant shift in the university’s approach to its older buildings,” O’Rourke wrote in an email interview. “When property owners seek the designation, it is taken to mean that they value the historical aspects of their buildings, want them to be recognized as historically significant, and that they intend to be good stewards of them.”

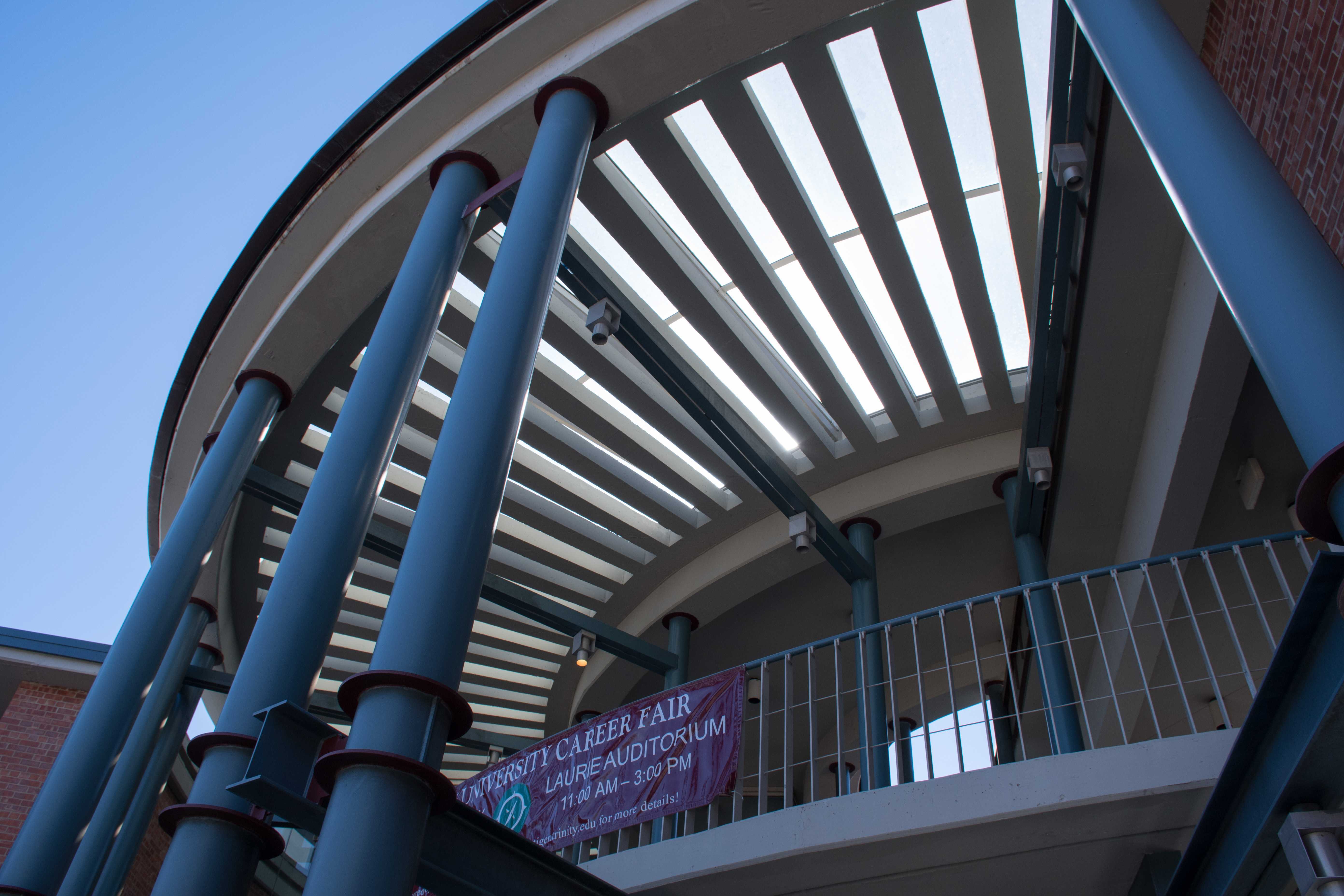

According to Bohmfalk, 26 buildings across campus are a part of this designation. These include residence halls like Bruce Thomas Hall and Camille Lightner Hall, as well as academic buildings, including George Storch Memorial Building and Laurie Auditorium. Buildings that were not designed by Ford, including the Center for the Sciences and Innovation, will be classified as non-contributing buildings in the district.

With the disignation as a National Historic District, the architecture will become more of an increasing focal point for the university.

“Our master plan is a recipe for looking into the future about what we want to do on campus. It’s about coordinating different uses across the campus, and a historic district I think is something that helps and supports our design guidelines that are part of that master plan,” Bohmfalk said. “I think that it encourages study of Ford and his way of thinking about architecture, and how architecture affects a university campus.”

O’Rourke also argued that Trinity’s designation will further shift the campus’s attention towards Ford’s influence — something that students have sought to preserve as well.

“The university understands pursuit of the designation as part of the master plan, which, rhetorically at least, aims to reconnect Trinity to principles that shaped the campus when Ford and his colleagues worked here. To do this meaningfully, Trinity must commit to patronizing designs marked by careful, deep engagement with the site and landscape,” O’Rourke wrote. “I hope that the university will commission a landscape master plan to complement the existing master plan.”