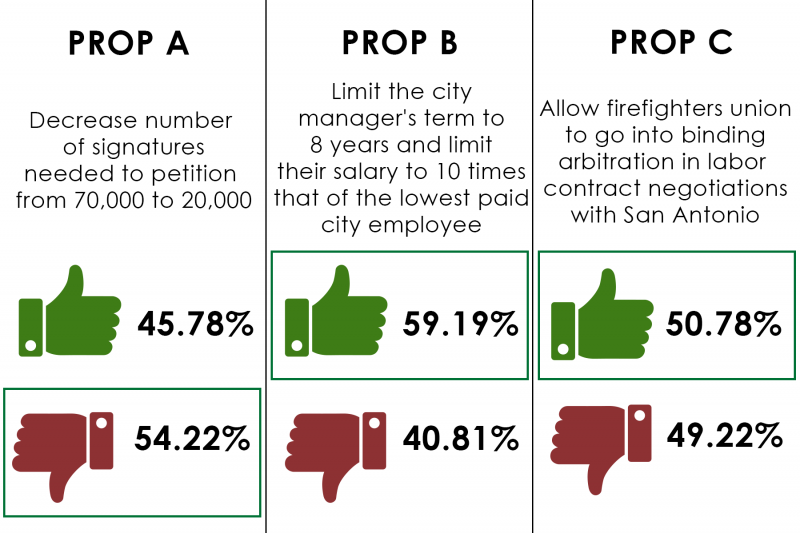

San Antonio community members voted on Propositions A, B and C when they went to the polls for midterm elections on Tuesday, Nov. 6. The three propositions were spearheaded by the San Antonio Professional Firefighters Association and sought changes to San Antonio’s City Charter.

Proposition A would decrease the number of signatures needed from 70,000 to 20,000 signatures. According to Ballot Pedia, it failed 45.78 percent to 54.22 percent. Proposition B passed, 59.19 percent to 40.81 percent. This proposition will limit the city manager’s term to eight years and salary to ten times the lowest paid city employee. Proposition C, passed 50.78 percent to 49.22 percent, will allow the firefighters union to use binding arbitration in labor contract negotiations with San Antonio. 550,786 people took to the polls, totaling 49.86 percent of registered voters according to Bexar County’s website.

David Crockett, chair of the Department of Political Science, believes the firefighters association grew frustrated after being unable to negotiate a new contract with the city. The union has been without a contract since their last contract expired in 2014.

“This is driven by an animosity for the city council, so the drive was to relax what is required to take city council decisions and put them on the ballot for the citizens to decide. It’s an attack on the city manager — not the current one, but it limits what the city council can do. Proposition C makes the city deal with the firefighters union on their contractual issues. This is all a fit of pique by one interest group against the city establishment,” Crockett said.

After the results came in, Crockett was shocked that the decision on the propositions was split.

“It was interesting to me that it was a split decision. I would have thought that either all three would have passed or all three would have failed, and that didn’t happen. So, people do I guess read the ballot measures and make their own decisions. Not everyone was persuaded by the ‘vote all yes’ or ‘vote all no,’ ” Crockett said, referring to the “Go Vote No” campaign encouraging voters to vote against each proposition and the rival “Vote Yes” campaign.

Crockett believes citizens may not have been aware of the ballot measures until they arrived at the polls.

“If you don’t consume a lot of news and you don’t read a lot of pamphlets that bombard your doors and you don’t pay a lot of attention to yard signs, this might be the first time a lot of voters actually confronted these propositions, and they have to read it for the first time. It wouldn’t surprise me that voters made decisions on the fly,” Crockett said.

Christine Drennon, director of urban studies and professor of sociology and anthropology, foresaw potential problems with Proposition A if it had been approved by voters.

“We elect representatives who we feel would do a good job representing us. We do not vote on every single issue and to have 20,000 people able to put an issue on a ballot is a really low number and a really low threshold, so it turns us almost into a populous-type governing body. The other argument is that special interests could easily buy it because in order to collect signatures, they usually pay canvassers,” Drennon said.

Before Proposition A failed, Drennon was concerned about San Antonio’s future bond rating. With the passing of Propositions B and C, Drennon believes there is less cause for concern.

Currently, the city maintains a AAA bond rating, demonstrating low risk for potential investors.

“We are one of the lowest risk cities in the country, and that is due to the fact that our city manager is extremely conservative financially. The rating agencies are much more favorable to things like investment in the physical landscape versus investment in human capital,” Drennon said.

To maintain this rating, the city focuses on physical investments into buildings, infrastructure and land. Due to the low-risk rating, the city is able to borrow more easily.

“So we have these enormous bond referendums where we go to borrow 80 million dollars in the bond markets in order to have physical improvements in the city. Theoretically, that frees up our own money to put into social services. Are we doing a good job? That depends on who you talk to,” Drennon said.

With a lower bond rating, Drennon believes there could be cuts to social services, affecting families across the city.

“A lot of our social services, especially for limited-income families, are paid for — but with public dollars versus private, not through the market. If our bond rating changes and we have to reorganize our budget, that might mean that social services are probably one of the first things to take a hit,” Drennon said.

John Huston, economics professor, is concerned with how Proposition B could affect the search for a new city manager.

“I don’t know what the future market is going to look like for city managers, but to get somebody good, you may have to pay more than this cap. Now you’re asking someone to come for what could be a salary below what you’d expect to get someplace else and to have a limited time. If you’re moving a family, it may be tough to get really good people to take the job,” Huston said.

To combat this, Huston thinks this may change the city’s incentives to contract out low-paid jobs.

“One way to get around this is not to have really low-income people on your payroll. So what they’re hoping for, of course, is you raise all their wages. But another possibility is if those low-income people are say, custodial people, that you now contract those out. I’m contracting with a company, I’m not paying them directly, so they’re not on my payroll,” Huston said.

Additionally, the city could choose to hire fewer low-wage workers.

“There could be a low-income initiative. Say students of Trinity University are given internships where they’re paid very little, but the idea is they get a great experience. The city might not want to do that because if they’re paid a low hourly wage, that then limits what they can pay the city manager,” Huston said.

Huston foresees Proposition C will potentially have unfavorable effects from the city’s point of view.

“It gives them a tool that the city doesn’t have in bargaining with them. That is they can go to binding arbitrary immediately without having been required to bargain in good faith to start with, so that really gives them an upper hand in negotiations,” Huston said.

Because the city has limited resources to allocate, inability to decide the allocation of resources could be frustrating.

“The other thing is this is a budgetary issue. I’m sure the city council would like to pay [fire department employees] more. But this then puts that into the hands in some external arbitrator, and from the city’s point of view, it might not like the outcome of that. So it’s got budgetary impacts is the idea,” Huston said.