Photo provided by Elliot Blake

Following a presentation by senior environmental studies students, the university is looking into the addition of solar panels to the new Chapman-Halsell building and potentially across campus.

The Chapman-Halsell project includes the creation of a new and separate building connected to Chapman-Halsell by an outside walkway. Gordon Bohmfalk, university architect and director of sustainability, hopes to add solar panels to the roof of the new building.

“We’re looking at adding solar [photovoltaic (PV)] to the new project, Chapman-Halsell. Right now, we’re looking at adding about 110 kilowatts on that building, at about $3500 a kilowatt. Most campuses take advantage of putting solar panels on their facilities, and I think that it would be great for us to get in to that, and hopefully the Chapman-Halsell new building is something that we’re able to afford,” Bohmfalk said.

Rice University set a goal in 2014 to be carbon-neutral by the year 2038. Using Rice’s program as an example, senior Elliot Blake, along with three other environmental studies seniors, created the Trinity University Solar Initiative for their senior seminar presentation.

“We decided to center our project around this idea that Trinity has all the resources available to support a solar panel system, and it just doesn’t make sense why we don’t have one,” Blake said. “We don’t want Trinity to fall behind the curve. We want Trinity to be a precedent to really set an example for students in the future of what it means to live sustainably.”

Currently, Trinity runs mainly on electricity produced by coal-fired power plants as well as solar power from San Antonio’s City Public Service (CPS) solar power grid.

“We have a contract and we get tapped into the CPS city power grid. We pull off 15% of their solar field that they have south of town,” said Richard Reed, professor of sociology and anthropology as well as chair of the University Sustainability Committee. “I would say that of our electricity, 85% of its coming from coal-fired power plants, but 15% is coming from solar already.”

This potential addition to the new building would not be the first time solar panels has been used on Trinity’s campus. Back in the 1970s, there were panels on top of the Bell Center.

“They were part of an experimental solar project that was funded by the federal government, but when funding dried up for solar energy, the project was scrapped — and they were really inefficient solar panels,” Reed said.

Bohmfalk explains that inevitable remodeling of a roof often leads to the removal of solar panels, which may explain their absence on top of the Bell Center. This presents another financial issue when deciding to install them along with the expense of the panels themselves.

“I’m not quite sure why we don’t have them there anymore, but it’s probably due to a remodel. One of the things that I’ve always faced is when solar PV goes on a roof, eventually the roof has to be maintained and so the panels require removal, so that can be an extra expense,” Bohmfalk said.

Although there are many variables to consider, solar panels generally pay for themselves in five to 10 years according to Bohmfalk and Blake. While data has been collected to measure how quickly a solar panel will pay for itself financially, it is not known how long it takes for a solar panel to offset the carbon released during the production of the panel.

“Even though many people associate solar panels with being clean, renewable energy, the process of actually implementing, installing and getting together the fundamental pieces of a solar panel is extremely dirty work. The biggest con that we’d face is how quickly would solar panels be able to pay back what they expended in terms of carbon. Of course finances are a big part of it, but really we’re concerned about how quickly can we pay back that carbon expenditure,” Blake said.

Nevertheless, Reed explained that the production of solar panels is nowhere near as polluting as the excavation and production of other means of energy.

“There are a lot of benefits to solar panels, [such as their] reduction of the toxins that coal puts out and the protection of the forests that the coal is mined out of. The mining of coal is really destructive of the local landscape. The second damage is the toxins that are in the coal get released when they burn coal and its extremely destructive in terms of global warming,” Reed said.

Although difficult in terms of cost and installment, solar panels have their positives and Bohmfalk has ambitions and ideas for Trinity to be run majorly on solar PV.

“It’s not only the cost of the panel but what you get in payback. The solar panel itself generally is considered something that produces for 20 to 25 years. There is some maintenance for that, but essentially you’re getting free energy after seven years or so. That especially is a good payback if energy costs go up, which likely they will. It’s a good deal, it’s a good thing,” Bohmfalk said. “I really like thinking about solar PV in places where they’re also provided shade. Like parking areas, roof decks and parking garages — it would be great to add solar PV to the top level so then we have shade on cars.”

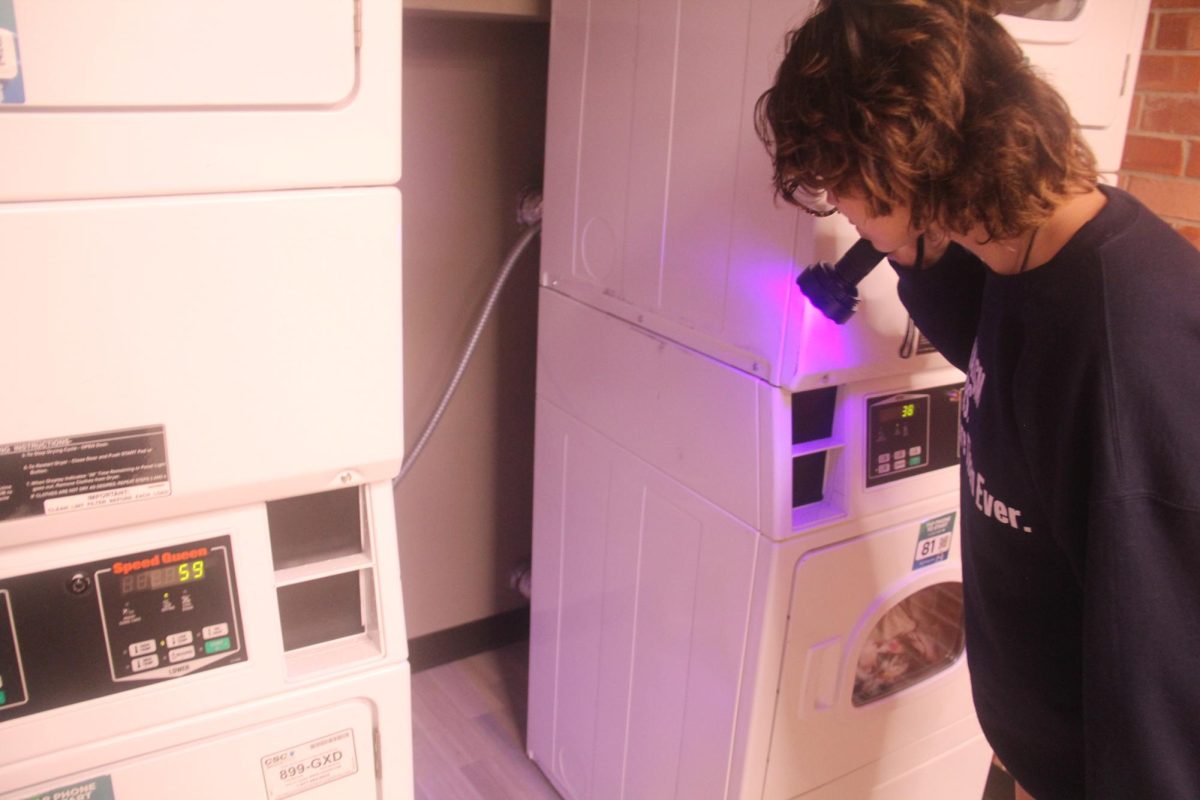

Blake also presented the potential for solar panels over parking lots during the Solar Initiative presentation. They presented mock-ups of an awning system and what that could look like over the parking lot behind Laurie Auditorium. The system would produce solar PV as well as light up the parking lot.

“Along with clean, renewable energy, some of the designs we presented the other day had a lot of applications in terms of improving student safety on campus,” Blake said.

According to Blake and Reed, the Center for Science and Innovation building has roofs that are wired to accommodate solar panels. However, solar panels would not have to be placed on Trinity’s campus at all.

“Trinity has a great access to a great deal of land in West Texas. We could produce solar energy with West Texas that we could sell into [San Antonio’s solar] grid and use it to buy solar energy here locally. By putting solar panels on tops of buildings or over parking lots or even in solar farms west of town, we could increase the amount of solar energy that we use. Now, the question becomes how much money do people want to invest into buying solar panels and installing solar production facilities,” Reed said.

Reed also believes that the motive to move towards solar energy shouldn’t just be about the profit Trinity could make.

“Solar energy is something that has continuous production without cost. The only cost is on the initial investment. But in addition to that, I think it has tremendous educational value. Solar energy on campus is an example of and a test case of the benefits of solar energy. If the students at Trinity see solar energy on campus, they’re going to think about putting solar energy when they move off campus,” Reed said. “We’re an educational institution, and one of the things that we do is we’re modeling for ourselves and for the rest of the world how things could be done better.”

Lubi solar • Aug 14, 2019 at 1:07 am

Yes solar energy have a bright future in all kinds of campus, with the solar energy we can do two things 1: We can save energy and Eccentricity Bill for us and 2: We can save our valuable environment for our child and for us also.

Ajay Verma • Jun 8, 2019 at 3:02 am

Solar energy is an environmentally friendly way of producing electricity. The electricity produced by your solar panels will be used to power any appliances. This article describes Does solar energy have a bright future on campus? I read your blog thoroughly and I enjoyed it.