Graphic by Quinn Butterfield

Over its 150-year history, Trinity has been funded with money created from oil and gas drilling. As the climate crisis looms, some professors and students think it’s time to undo that.

Throughout Trinity’s existence, numerous people involved in the oil and gas industry have donated to the institution. These gifts came from donors primarily between the 1950s and 1960s, according to Craig Crow, Trinity’s director of investments in the Department of Finance and Administration. These donations, which stand at about a $60 million value today, have provided financial support to the university.

“Trinity has been distributing most of the cash flows received from these interests into scholarships, departmental budgets and building renovations, and any additional cash flows from these gifts have been reinvested into the general endowment pool, which is a much more diversified set of assets,” Crow wrote over email.

While Trinity does receive money that comes from oil and gas, Crow emphasized that they funnel the donations into ventures that attempt to mitigate the environmental impacts of the source of the money.

“As an example, cash flow from the minerals portfolio funded 50 percent of the CSI construction — a building devoted to sustainability. Overall, the University has not reinvested any of these dollars to add to our mineral holdings, rather reinvesting in significant university initiatives or creating non-mineral oriented endowments that support scholarships and other mission-related endeavors,” Crow wrote.

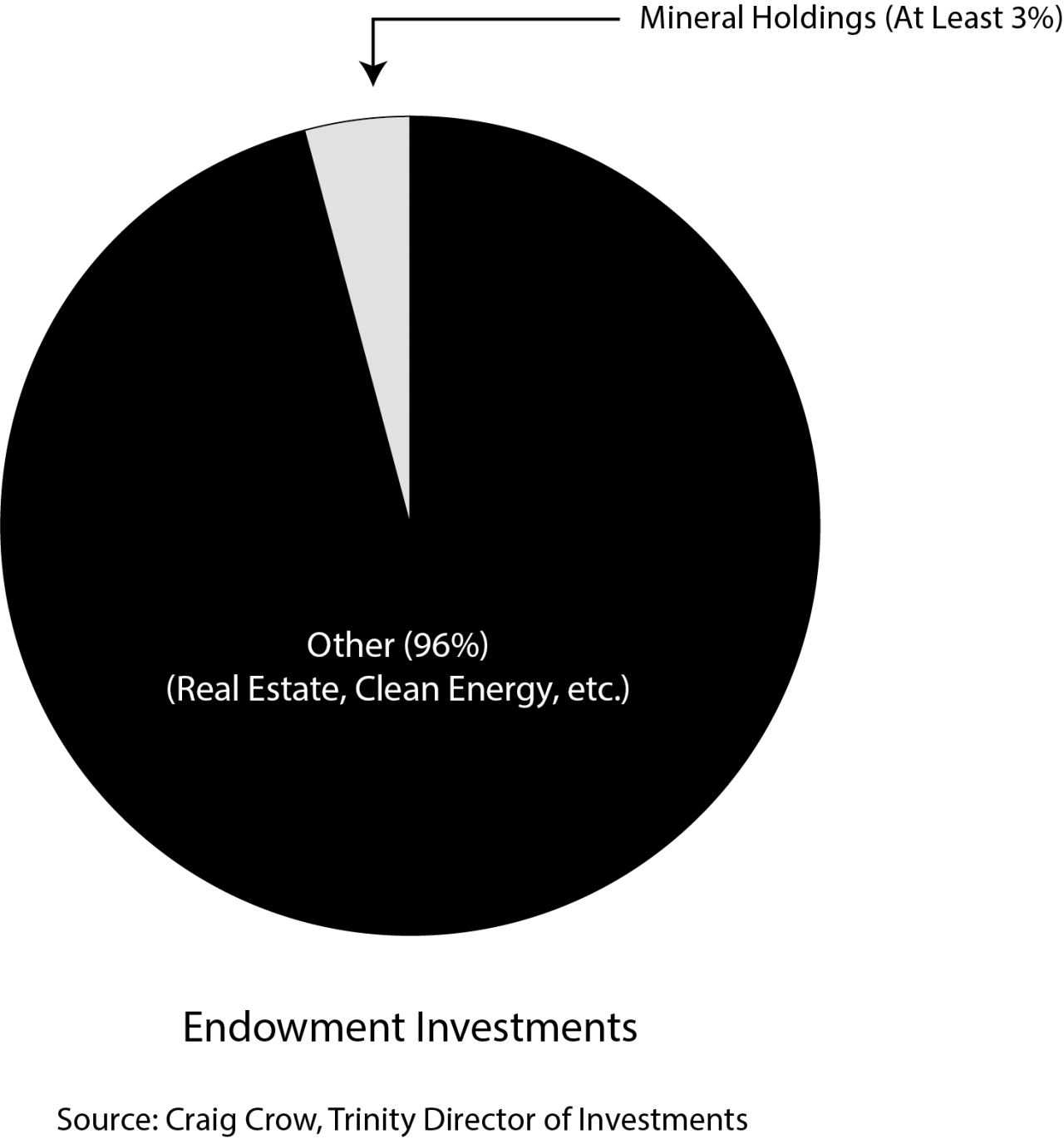

Outside of donations to Trinity, money is made through the endowment’s investments in mineral holdings, historically in oil and gas. This means that the investment fund reflects that of a public index, which holds the largest US-based publicly traded companies. Companies within this include Exxon, Chevron and Occidental Petroleum. About five to six percent of the companies in this public index are in the ‘energy’ sector which includes fossil fuel producers, energy service companies and materials that aren’t fossil fuels like metals and gold.

Active investments are made into oil and gas drilling companies, but they are a very small portion of the endowment’s current value, according to Crow, and no active investments are made into coal. Not including gifts to Trinity, money from oil and gas make up about three to four percent of the endowment.

Senior Katherine Jones, president of EcoAllies, distinguished the difference between receiving donations and directly investing but ended up at the same conclusion for both.

“I’d say that it’s probably a lot more straightforward for a university to try and divest from their own oil holdings versus discerning whether or not someone is donating oil money that they’ve earned. I think that there is a difference, but ultimately it’s the same outcome — Trinity is profiting from oil and gas money, which kind of means that the sustainability of the university is at odds with the sustainability of the environment and our society in the long-term,” Jones said.

Richard Reed, professor of anthropology and sociology, believes that while it’s important to understand the difference, Trinity’s foundation built on oil makes it much more difficult to stray from oil money.

“Is it wrong to accept a gift of money from these people? Is it of any use to refuse it? It’s not just putting stocks and bonds in oil wells. It’s the way oil is really woven into the fabric of the university from the very start. Maybe it’s time to move away from our deep involvement with petroleum,” Reed said.

Reed doesn’t rest all of the blame on Trinity though.

“We’re all invested in oil. Do you have a car? What does it use? You’re invested in oil. We’re all implicated in the tragedy of oil, we’re all a part of the process and some people are more directly and aggressively and more central to the process. But I don’t think any of us can walk around with a clean conscious,” Reed said.

Jones recognized her place as a student in this process as well.

“We all benefit from that just by going to Trinity. It’s not straightforward, but ultimately, Trinity is paying for most of our educations with oil and gas money. I think that in the long term that should shift because either they’re going to keep investing in oil and gas, and oil and gas is going to keep growing, and it’s going to deteriorate the environment, or oil and gas is going to decline, and Trinity’s not going to have a very stable financial base anymore. The longterm best option would be to divest,” Jones said.

Trinity has begun this divergence. In 2017, the university made its first investment into a fully renewable private investment fund, using money from the endowment, and it will continue to look into more renewable energy prospects like this, according to Crow.

“This fund’s investment mandate only allows money to be invested into sustainable assets — examples being solar, wind and other renewable energy outputs. The platform tracks its environmental impact, and its portfolio of investments negated (or avoided) 178,000 tons of carbon emission in 2018 alone through its renewable energy efforts,” Crow wrote.

The focus on fossil fuels will not waver just yet, as the Board of Trustees values the profits made from it.

“The board fully appreciates the donors who provided a strong foundation for Trinity’s endowment and recognizes that a lot of that, because we’re in Texas, came from families who made those fortunes in oil and gas,” said Tess Coody-Anders, vice president for Strategic Communications and Marketing.

There is no movement to sell.

“These mineral interests have been viewed by the Board of Trustees as a permanent fixture in the endowment versus a traditional financial asset that the Board would look to sell,” Crow wrote.

At least six of Trinity’s trustees are involved in the oil and gas company. One of these oil and gas trustees, Annell R. Bay (former vice president of Global Exploration at Marathon Oil Co.), was appointed this past September. Reed believes a shift in the board may cause a shift away from oil reliance.

“Rather than getting these petroleum men, they could get young women who are scientists, and that would really change the shape of the Board,” Reed said.

Coody-Anders highlighted the difficultly of this shift.

“Both the wise thing to do, and perhaps the 21st-century thing to do, is to look at what else should be doing with our money. We can honor the past, but it doesn’t mean we have to live there,” Coody-Anders said. “But it’s a bridge that we’re crossing over. We have both board members and investments that are helping us cross over that bridge.”