illustration by Andrea Nebhut

The first graphic novel I read was a series called “Bone.” It follows the Bone brothers and the many adventures they have, with the final book remaining to this day to be one of my favorites.

But my perception of graphic novels growing up, as important as they were to me, was that they were for kids and teenagers; colorfully rendered childish fantasies that adults, people who pay taxes and likee the news, would never read. I’d never seen my dad or any of my parents’ friends read graphic novels. The homogeneity of graphic novel readers I knew being teenagers and kids stayed true until high school, when I read the graphic novel “Maus” by Art Spiegelman.

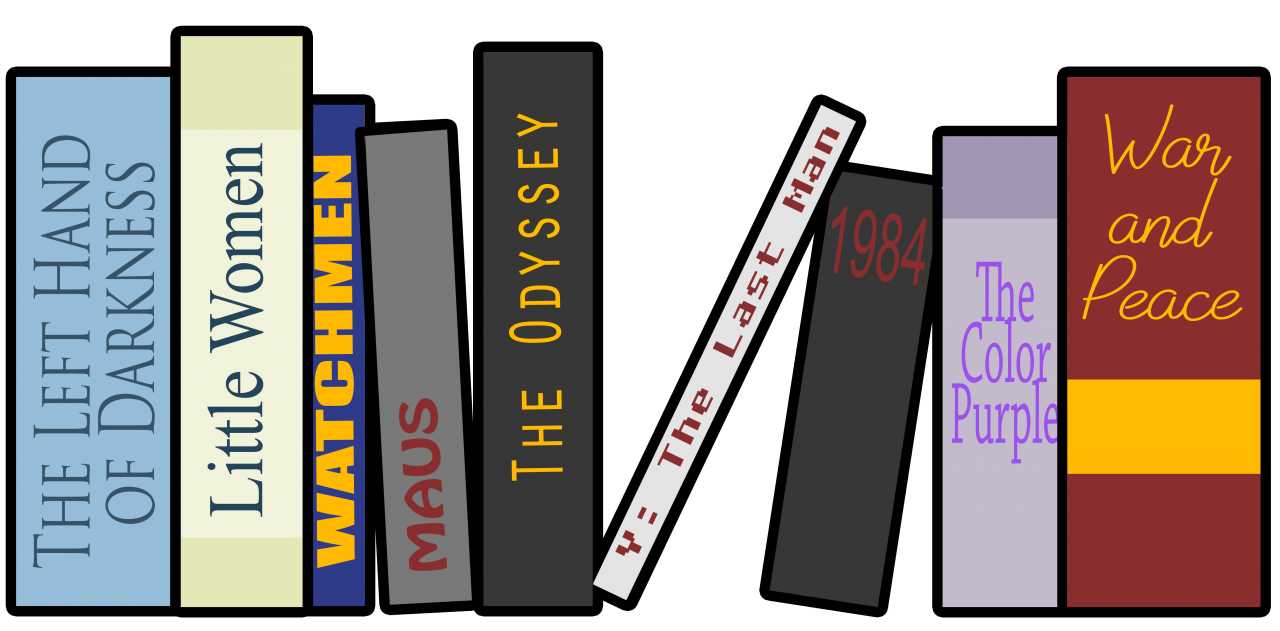

Widely acclaimed as one of the best graphic novels of all time, it won the Pulitzer Prize and was credited for bringing acclaim to the medium of graphic novels, along with “Watchmen” and “The Dark Knight Returns,” cementing their place in literary canon as novels to be respected and taught. “Watchmen” and “The Dark Knight Returns” are both graphic novels dealing with superheroes as vehicles for societal critique, yet “Maus” was heralded for different reasons — as a remarkable and moving retelling of Spiegelman’s father’s experiences of growing up in Hitler’s Europe. While a graphic novel, “Maus” is considered a work of non-fiction. It was the light that led “the American public, including many literary critics, toward seeing comics as a serious art form,” according to Michael Cavna for the Washington Post.

Learning about all of this in high school, it blew my mind that it took me till I was 16 for the first graphic novel to be taught to me in an academic setting. Why wouldn’t schools be clamoring to diversify their literary texts, to give students a taste of a modern medium, one born closer to their birth than the novel? There are so many incredible graphic novels, fiction and non-fiction, that can explain similar themes to the ones pounded into the English curriculum.

“Watchmen” is said to be one of the greatest works penned in the past 25 years. A work that, according to Author Robert Harvey “demonstrated as never before the capacity of the [graphic novel] medium to tell a sophisticated story that could be engineered only in comics.” So why is it that I never read “Watchmen” in high school or any of my college classes? How many times must one read “Frankenstein” to get that it’s about the spark of life? How many more students will have to read “The Metamorphosis” before they can maybe get the chance to read just about anything else?

Graphic novels have demonstrated their ability to deal with complex issues, and even superseded novels by rendering difficult themes in ways that traditional novels simply can’t. That isn’t to say novels of the non-picture paired variety should be completely thrown out, but that the overall themes of any English, history or communications course would be heightened by adding some flavor in the form of “Watchmen” and “The Dark Knight Returns” to the curriculum.

Graphic novels are an example of the changing literary landscape, the result of decades of comics slowly shedding their World War II and Cold War descriptors and emerging as texts capable of being as impactful and artfully curated as any other novel. An example would “Y: The Last Man” by Brian K. Vaughan, which follows the adventures of the last man on earth after an unknown disease wipes out all organisms with the Y chromosome. It has won three Eisner Awards, the highest honor in comics, and got second place for the Hugo Award for the best graphic novel as well, the highest award in science fiction. Vaughan is currently on a series called “Saga,” a space opera that tells the tale of a war that has ripped galaxies apart and the birth of a girl that changed the course of destiny. It has won 34 awards over its 7 years in publication, one of them being the Hugo award in 2013. It is incredible and a novel I believe that should be taught in any English curriculum that is working to discuss issues of war, race, sex, gender and power.

Graphic novels are no longer considered fodder for the young but they should begin to be taught as what they are, testaments of literary evolution; full of depth, complexity and beauty. Works on par with the best that novels have to offer. It’s time they shook the boat of the “literary canon” and show that having pictures in a book doesn’t make it easier to read, it just means there’s more to see.