Opinion: NCAA washing their hands of NIL will change the landscape of college sports

NCAA interim policy allows student-athletes to monetize name, image and likeness

The crux of the NIL issue is often framed as fairness. The argument for student-athletes receiving compensation for their name, image and likeness (NIL) is that it is only fair that the athletes get paid considering how much revenue they bring in for the institution. However, as straightforward as the idea of paying student-athletes for the use of their name, image and likeness the issue is more complex than it first appears.

The interim policy that went into effect July 1 allowing student-athletes from all three divisions to monetize their NIL is the catalyst for rules and decisions that will irrevocably change the landscape of college athletics for the next decade. The question is whether that change will be for the better and whether the potential benefits will be equitable.

What is NIL?

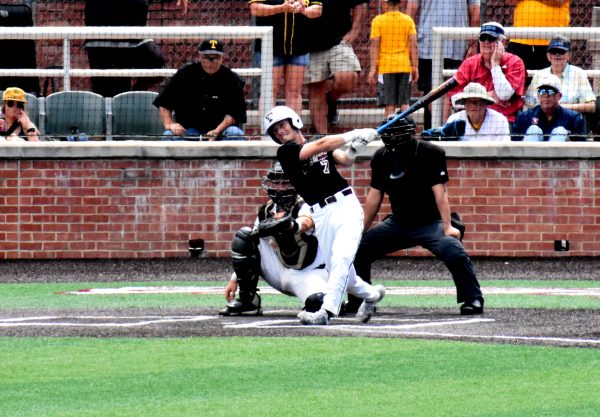

One of the biggest distinctions between collegiate and professional sports is the issue of compensation. While NIL won’t allow student athletes to receive pay-for-play, over the past few months there have been significant changes in what types of compensation athletes can receive at a collegiate level.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is the foremost governing body for collegiate athletics in the United States, and their main priority — at least in terms of the issue of athlete compensation — is to maintain a clear product differentiation between collegiate sports and professional sports. In fact, the NCAA has used product differentiation as a justification to prohibit certain types of compensation for student athletes — including a subset of educational benefits like tutors, post-grad fellowships and instruments. The argument is that if players receive compensation, it will be too difficult to differentiate between collegiate and professional sports and it would hurt viewership.

The issue of product differentiation was the crux of the issue in the NCAA vs Alton case. The Supreme Court ruling on the case on June 30 determined that the prohibition of compensation — specifically the refusal of certain education related benefits — violated antitrust laws, although the product differentiation justification remains sufficient for other forms of compensation.

Amid this paradigm shift regarding compensation for collegiate athletes, one would expect that the NCAA would put in place very strict rules about NIL to help maintain product differentiation, but they didn’t. Instead, the NCAA announced an interim policy that went into effect on July 1 that allows student-athletes from all three divisions to monetize their NIL.

The interim policy was a response to new NIL laws passed individually at a state level which were meant to come into effect on July 1 — like California’s Fair Pay to Play Act. The NCAA directed schools and conferences to follow their state laws regarding NIL or to make up their own rules.

This hands off approach from the NCAA means that there is no uniform rule and therefore no enforcement or consequences for breaking the rules. For example, NIL shouldn’t be used as a recruitment tool or pay-for-play, but Brigham Young University (BYU) is using an NIL deal with Built Brands to give their football team walk-on’s “scholarship equivalents” as a way to get around the 85-man scholarship limit.

The Snowball Effect

NIL is the new Wild West and the snowball effects from the NIL ruling and the NCAA vs Alston Ruling will fundamentally change the landscape of college sports forever.

Already, student-athletes are petitioning to receive employment rights.Of course this is nothing new —

the NCAA even coined the term “student-athlete” in the 1950’s to argue that injured football players couldn’t receive workman’s compensation— but in the light of NIL and the Alston ruling, college athletes getting employment rights seems more plausible.

If right-to-work states decide to give collegiate athletes employment rights, it would give schools in certain states an edge when it comes to recruitment. That isn’t to mention that the athletic departments wouldn’t be able to survive, since giving athletes employment rights would mean losing 35% of their revenue stream.

It’s simple Darwinism. Unlike professional leagues, like the NFL, which operate on the principle that they are only as strong as their weakest team, college sports are every-man-for-himself. Universities may eventually have to make difficult decisions and cuts in order to preserve their athletic departments.

When it comes down to it, it’s going to be women’s sports and “unsexy” sports — like golf or cross country — that bring in less revenue that are going to get the short end of the stick, while the big money makers, like football and men’s basketball, will receive priority.

It may seem like this prediction is overly-apocalyptic, but NIL does not exist in a vacuum. The legislation surrounding the issue of compensation for student athletes made in the next few years will impact collegiate athletic departments that have never had to account for compensation before; and NIL could potentially be the first step in college sports transitioning toward a semi-professional model.

I would like to be clear, I’m not trying to argue whether or not student athletes should receive compensation or whether or not these changes would be good or bad. Frankly, I think that athletes being able to monetize their NIL at a collegiate level is a wonderful opportunity for them to earn money and even pay for their higher education. However, the concern is that if collegiate athletics shift towards a semi-professional model the priorities of athletic departments will change and potentially harm athletes.

After all, what is the purpose of college athletics? Is it a vehicle for athletes to receive higher education? Is it a recruitment pool for professional sports? Is it a way for universities to make money?

Under a semi-professional model, athletes are employees not students and the priority, therefore, becomes generating revenue rather than athletics. We can already see the shift towards changing priorities in the wake of the NIL ruling.

In order to get NIL deals in the first place, athletes are going to have to spend time cultivating their image and their presence on social media. Being good at your sport is all well and good, but more than that sponsors want name recognition and popularity. If you see a fast food commercial starring Chuck Foreman, instead of thinking about the advertised product, you might be left thinking “Who was that random guy?”

The need to cultivate your image could potentially harm academic performance by forcing students to prioritize their social media name recognition over their education.

This is especially a concern for Black and underprivileged athletes. While NIL deals could potentially be very lucrative for Black and underprivileged students-athletes, there is a past precedent of these athletes getting less out of their education. There exists racial inequities in six-year graduation rates and benefits and engagement outside of athletics, as well as a disparity in post-graduate life outcomes for DI athletes who didn’t go pro.

One of the reasons this inequity exists is because coaches, who set the educational standard for their athletes, prioritize athletics over academics and discourage participation in activities outside of sports. Valuing athletic performance above education can harm a student’s education and hinder their degree path — especially when the student already starts out at a disadvantage.

NIL adds an entire new dimension to the disparity that already exists by introducing something else for athletes to prioritize over their education.

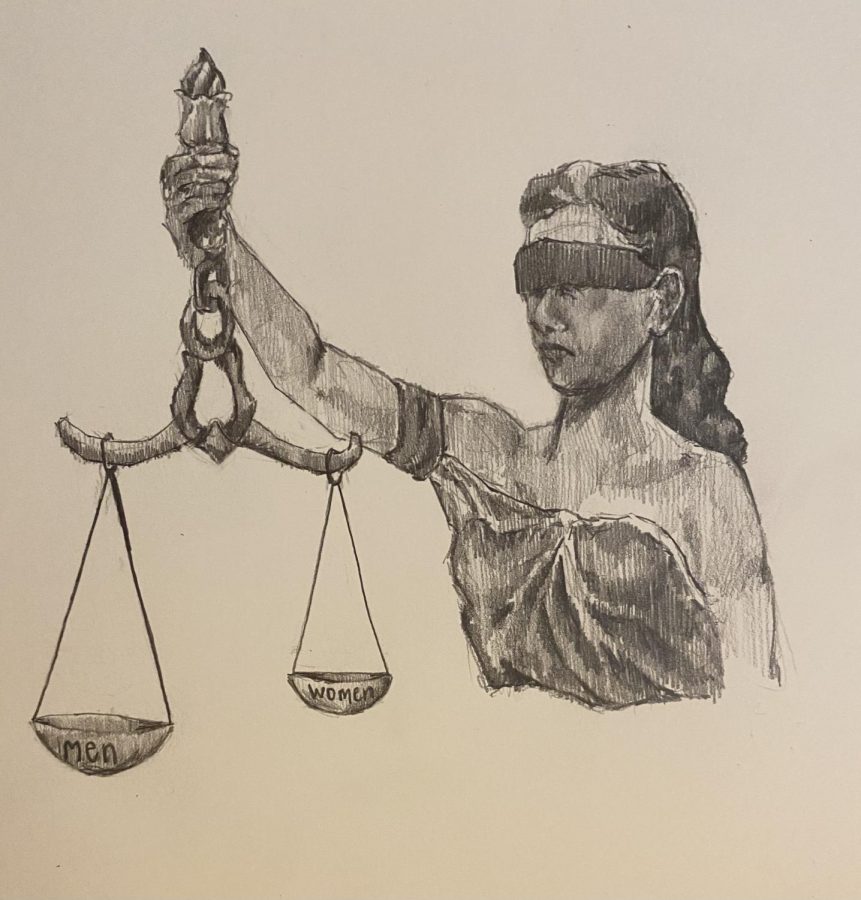

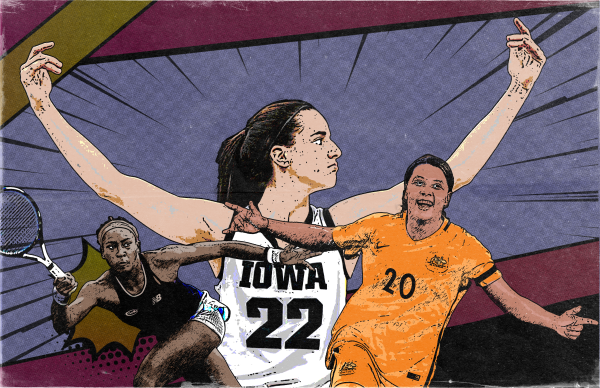

The issue of priority isn’t limited to harming academic performance. There is past precedent for men’s sports being prioritized over women’s sports in the NCAA, and as a result female student-athletes may be less likely to receive NIL deals than their male counterparts.

Of course, it’s to be expected that athletes from more popular sports will benefit from NIL more than athletes from sports with less viewership. After all, football and men’s basketball are the big money makers for the NCAA, so it’s only natural that they get priority. However, it is important to acknowledge that part of why these sports are such heavy hitters is because the NCAA’s structure prioritizes men’s sports over women’s.

According to the NCAA 2021 Gender Equity Review conducted by outside parties, the NCAA’s structure and culture prioritizes men’s sports over women’s. The place where we can see this most clearly is in basketball, specifically in terms of the media agreements that the NCAA has. CBS owns the broadcasting rights to the NCAA Men’s Basketball, as well as the NCAA’s Corporate Sponsorship Program for all 90 NCAA Championships — which means that any potential sponsors or advertisers have to go through CBS. Simple and straightforward.

However, CBS doesn’t own the broadcasting rights to the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournaments — ESPN does. And this is where things get complicated. If a company wanted to air an ad during March Madness for Division I Women’s Basketball, they would have to buy into the NCAA’s Corporate Sponsorship Program. Meaning, they would have to pay CBS for the rights to all 90 championships and then buy airtime from ESPN. As a result, companies are less willing to enter into partnerships and sponsorships for the women’s basketball tournament, which in turn leads to women’s basketball having less resources than their male counterparts, even as their popularity and viewership continues to grow.

The very structure of the NCAA makes it harder for women’s sports to bring in the same revenue as male sports. And since universities that offer NIL deals to their athletes are going to prioritize their most lucrative sports, female athletes will always end up with the short straw.

And although female athletes could receive compensation for their NIL independently of the school, if the NCAA doesn’t prioritize female athletes, why should potential sponsors? If collegiate sports shift towards a semi-professional model where profits are the priority, will women’s sports be worth the investment?

It is still unclear what the future of college athletics is going to look like when it comes to player compensation. The current NCAA hands-off interim policy is by definition only a temporary measure and eventually rules and legislation will have to be put in place and enforced. The question now is, what is the priority? Is the priority student-athletes or profits?

If we aren’t careful, we may end up with a system that harms student-athletes and only benefits a select few. It’s therefore essential that there is a diverse, intersectional group of people who have a seat at the table where these decisions are being made. The issue of compensation is going to dominate the landscape of collegiate athletics for at least the next decade, and so I think that priority should be making sure that it is an equitable change for the better.

My name is Alejandra, and I'm a senior majoring in Neuroscience. I initially joined the Trinitonian as a first-year and worked my way up from a Sports...

Hi, my name is Jaida and I am an illustrator for the Trinitonian. I am double majoring in international studies and art and I started working for the trinitonian...