Opinion: Mental Health vs playing through the pain

While discussions on mental health change, athletic culture still prioritizes performance over people

1996. Atlanta. It’s the Olympic Games, and USA gymnast Kerri Strug is stepping up to her mark for her first vault attempt. A sub-par performance by a teammate meant that it was up to 18-year-old Strug to right the ship and bring home the first-ever all-around team gold for USA Gymnastics.

She heard the crack of her left ankle when she fell back on her landing.

Visibly limping, Strug walked back to her mark and prepared for her second attempt. She stuck the landing on one foot, securing gold for the U.S. and making Olympic history. Strug had to be carried to the podium.

Decades later, this moment is still one the most talked-about moments in sports history. Strug is lauded for her ability to push through the pain — and you can see the pain on her face in the photographs — and bring her team a victory.

What people don’t talk about is the immense stress that Strug was under. No one stops to consider how the pressure placed on her shoulders may have been a factor in her failed attempt at a vault she had landed thousands of times in the past, and although coach Bela Karolyi received some backlash, it’s the image of him carrying Strug to the podium that people remember, not him telling Strug, “We need it. We need it,” even as her leg buckled beneath her.

I’ll admit, when I was an athlete, I found Strug’s story wildly inspiring. I took pride in my mental fortitude and my ability to “play through the pain.”

Of course, high-school volleyball isn’t nearly as high-stakes or perilous as Olympic-level gymnastics, but I still disregarded my physical and mental well-being for the sake of athletic performance and considered it a badge of honor.

I can easily think of a few examples off the top of my head. I remember practicing and playing on an ankle swollen to twice its normal size. I remember losing a contact lens at a tournament and playing an entire match with one eye closed, but maybe the most poignant example that comes to mind is the time I played an out-of-town tournament the same day as my father’s funeral.

Much like Strug, it was my own decision to do these things. When Karolyi said, “We need it,” Strug said, “All right.” She could have said “No.”

If you ask me, though, I don’t think it ever occurred to Strug to say “no.” In order for her to get as far as she did, she had to buy into the culture tacitly endorsed by USA Gymnastics and Karolyi. A culture that is not limited to gymnastics. A culture that permeates every level of sports. A culture that I participated in as a student-athlete myself.

It’s a culture that values performance over people. It values “mental toughness” and the ability to “push through the pain.”

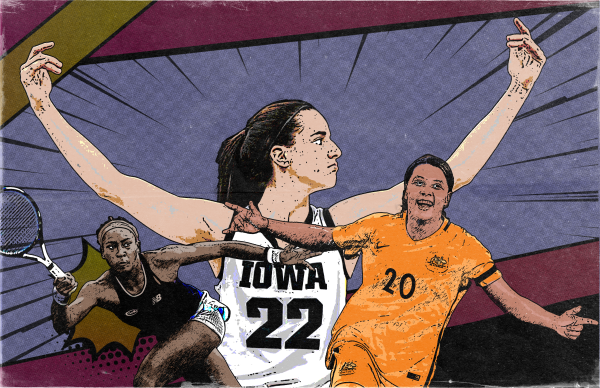

Over two decades after Strug’s famous 1996 performance, the discussion surrounding mental health in athletics has evolved. It came into the global spotlight this summer at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics when Simone Biles announced that she would be withdrawing from the team finals due to her mental health.

Biles was suffering from a mental block that gymnasts call the “twisties.” Essentially, she was losing herself in the air which put her physical safety at risk — especially considering that Biles incorporates elements in her competition routines that most other gymnasts can’t even perform.

Many people were supportive of Biles’ decision, including members of the famous 1996 Olympic team, the “Magnificent Seven.” Kerri Strug herself took to Twitter in public support of Biles.

However, Biles also received intense backlash for her decision. Many people called her weak and blamed Biles for USA Gymnastics’ leaving Tokyo with a silver medal instead of gold.

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand the perspective of those who were dunking on Biles. It’s a symptom of the “play through the pain” culture. How can she justify withdrawing from competition because she’s going to hurt herself when Strug secured a gold medal on a third-degree lateral strain? All athletes have to deal with nerves and pressure, so she should be able to handle it, right?

Ignoring for a minute that Biles went to the Olympics not only as herself, but as the star, the GOAT, the face of her nation, the backlash reveals a still prevalent attitude towards mental health in athletics. Athletes are expected to compromise their physical and mental health to perform. To entertain us. The response of the angry Twitter hoard to Biles’ withdrawal echoes Karolyi. “We need it.”

Modern athletes fall into the archetype of the “tortured artist.” The ideals of mental fortitude and playing through the pain parallel the idea that artists must suffer.

Strug’s 1996 performance wouldn’t have been remarkable if she hadn’t been in so much pain. If Van Gogh hadn’t been depressed, we wouldn’t have his artwork, but this isn’t true. Van Gogh was most prolific when he was hospitalized at Saint-Rémy; he painted around 150 paintings in a year, including his famous piece, “Almond Blossom.” If Strug hadn’t been injured, she still would have secured the historic gold, and if she had withdrawn from competition after her injury, well, she’d be a lot poorer, but Strug most likely would have gone on to compete at UCLA like she always planned to.

Athletes perform better when they are at their best both physically and mentally, so the only logical thing to do is prioritize the physical and mental well-being of athletes, even if that means letting them step back for a while.

That’s the practical argument. The humanist argument is that the mental health of athletes should be prioritized over their performance because they are human beings. If an athlete needs to leave their sport, the public should support that, even if it means we never get to see them perform again.

After all, they are people first, athletes second, and it’s often better to let the pain heal instead of attempting to play through it.

My name is Alejandra, and I'm a senior majoring in Neuroscience. I initially joined the Trinitonian as a first-year and worked my way up from a Sports...

Hi, my name is Jaida and I am an illustrator for the Trinitonian. I am double majoring in international studies and art and I started working for the trinitonian...