Untold heroes of Trinity women’s athletics

How Pasley’s “From the Sidelines to the Headlines” illuminates the champions of women’s athletics

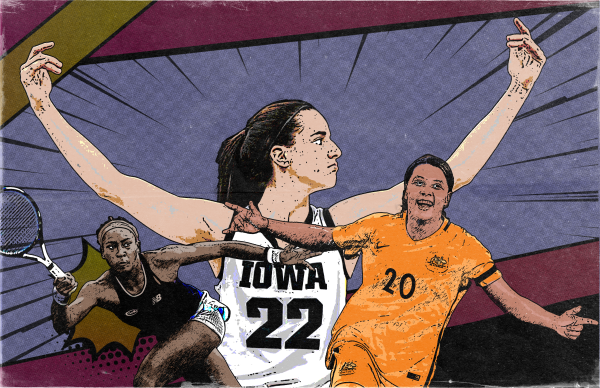

Abby Power (center) poses with Shirley Rushing Poteet (left) and Emilie Burrer Foster (right).

In a year like this one, when the Trinity Volleyball team is the national runner-up and the Trinity Women’s Basketball team is in the Sweet 16 of the national championship, it is hard to believe there was a time when women’s sports didn’t exist at the varsity, or even club level, at Trinity. Last week, I wrote an article about Betsy Pasley’s book, “From the Sidelines to the Headlines: The Legacy of Women’s Sports at Trinity University,” which painstakingly details the progress of how women’s sports came to prominence at Trinity University as well as in the United States. In the article, I mostly focused on the connection between women in sports and Title IX, but Pasley’s “From the Sidelines to the Headlines” holds many more valuable stories that have been left untold for decades.

Two of the narratives that Pasley shares with the world is that of Shirley Rushing Poteet and Emilie Burrer Foster. I had the great honor of meeting the two remarkable women on Sunday, March 5 at a panel discussing Title IX and women’s sports in San Antonio in conjunction with the publication of “From the Sidelines to the Headlines.” I nervously approached the two women, who were huddled together, conversing only in the way that friends of 50 years do. Right away, Rushing Poteet took my hand in hers. Between her and Burrer Foster, I was in the presence of two great legacies that had long since been buried.

Rushing Poteet’s journey started in Mississippi, where she played basketball and attend college. She ended up in Texas after graduating from a master’s program in physical education. She started at Trinity in 1960 as a physical education instructor, teaching classes and leading women’s sports programs as the only woman in the athletics department.

Rushing Poteet singlehandedly recruited and facilitated the first women’s tennis team on campus, advocating for more money than just the meager funds the team was offered and accompanying the team across the country for tournaments. In 1985, she became the head of the athletic department, an homage to her more than 25 years of service and dedication to Trinity athletics. She now graces the cover of “From the Sidelines to the Headlines” and was a part of the committee that led to the book’s creation.

A few years into her career, Rushing Poteet drove a talented young tennis player home from a tournament. Soon, that player transferred to Trinity University to join Rushing Poteet’s tennis program — a move that would forge Trinity history. The player’s name was Emilie Burrer Foster, and she went on to win four national championships during her time at Trinity as a determined student-athlete.

Trinity then hired Burrer Foster to coach the newly minted NCAA Division I women’s tennis team after having transformed the Texas Tech women’s tennis team. She continued her success at Trinity, leading the women’s tennis team to national championship tournaments. When her tenure as coach ended in 1990 she became a distinguished biomechanist. Burrer Foster now serves as a Trinity volunteer assistant women’s tennis coach.

While I’ve only given a brief summary of the illustrious careers of these two legends, it’s easy to see why I was starstruck upon meeting them. They both shared stories with me about how they became friendly with the administration in efforts to promote their programs and athletes. I asked them if they were ever apprehensive to so boldly break the social norms of the time by heavily promoting women in sports. Immediately, Burrer Foster responded that she never once questioned her determination to fight for her athletes and program.

I was in true awe throughout the conversation. Rushing Poteet and Burrer Foster championed women in athletics and athletics in general, long before their participation was socially accepted; nonetheless, they persisted to give women a chance to play the sports that they loved. Without these two ladies, it is safe to say that women’s sports at Trinity would not be as prominent.

Rushing Poteet and Burrer Foster are only two of the stories that Pasley chronicles in the book. Libby Johnson coached at least three sports throughout the year from 1972 until her retirement in 1980. She consistently championed women’s sports, even driving her athletes to tournaments across the country on her own dime. Glada Munt, 1975 Trinity alumna, rose the ranks in spite of discrimination to become the athletic director at Southwestern University, where she now presides as associate vice president for intercollegiate athletics. Yanika Daniels, a member of the panel, shared her story about fighting to have the Trinity women’s basketball team included in Midnight Madness, a basketball season tradition celebrated only by the men’s team.

Trinity’s history is marked by these women who made change and fought against discrimination in the arena of sports. Pasley does a beautiful job of telling the stories of these champions of women’s athletics throughout Trinity’s history, stories of people that have been relegated to the sidelines.

I have learned more in these past three weeks about women in sports at Trinity, and in the United States in general, than I had learned in my whole life prior to reading Pasley’s book, attending the panel and conversing with Pasley, Rushing Poteet and Burrer Foster. I would need more than these 800 words to unpack why these women and their stories have been neglected in broader discussions about athletics.

What I can say now, however, is that I am beyond grateful to Pasley and all of the contributors and supporters of “From the Sidelines to the Headlines” for bringing these stories to light, where they belong; they have changed my perspective about how to be an advocate for the issues in my life, and I imagine if you read it, the book will do the same for you.

Before my conversation with Rushing Poteet and Burrer Foster ended, I asked them to take a picture with me. Burrer Foster joked with me that I should print it out and practice darts with it. No doubt, I will print the photo out, but it will be hanging on my wall next to the other people in my life that inspire me.

Hello, y'all! I'm Abby Power, and I am a sophomore news reporter from Kyle, Texas. I intend to major in Political Science, Spanish, and Global Latinx Studies....

Shirley Rushing Poteet • Mar 10, 2023 at 2:37 pm

Abby, Jacob Tingle forwarded your article in the Trinitonian to me. Thank you so much for the beautiful article, with accolades far beyond what we deserve! It was a pleasure meeting and talking with you and I predict for you a great future, whether it be in journalism or any other field of endeavor you wish to pursue.

Thank you so much!!

Shirley Rushing Poteet