An “Urgent Town Hall” was held at Dicke Hall on Sunday, Sept. 29 by the Monte Vista Historical Association (MVHA). The seats were filled with impassioned, predominantly white elderly residents, save for one young woman sitting in the front row, sunhat and binder in tow. Enter Madelyn Fayge, my persona while deep undercover in uppity territory.

The town hall was assembled to address the City of San Antonio (COSA) and VIA’s plans for the Green Line rapid transit spanning the whole of San Pedro Ave. The meeting was also set to discuss specifics about zoning laws changing and the earliest stages of the Near North Sub Area planning — the tentative new zone to encompass Monte Vista and Trinity University. Throughout the discussion, emphasis was placed on “how to evolve without losing a safe, walkable neighborhood,” to “protect our historic character” and “heritage,” according to MVHA board member Rick Wilson. “Heritage” resurfaced as a talking point many times by residents.

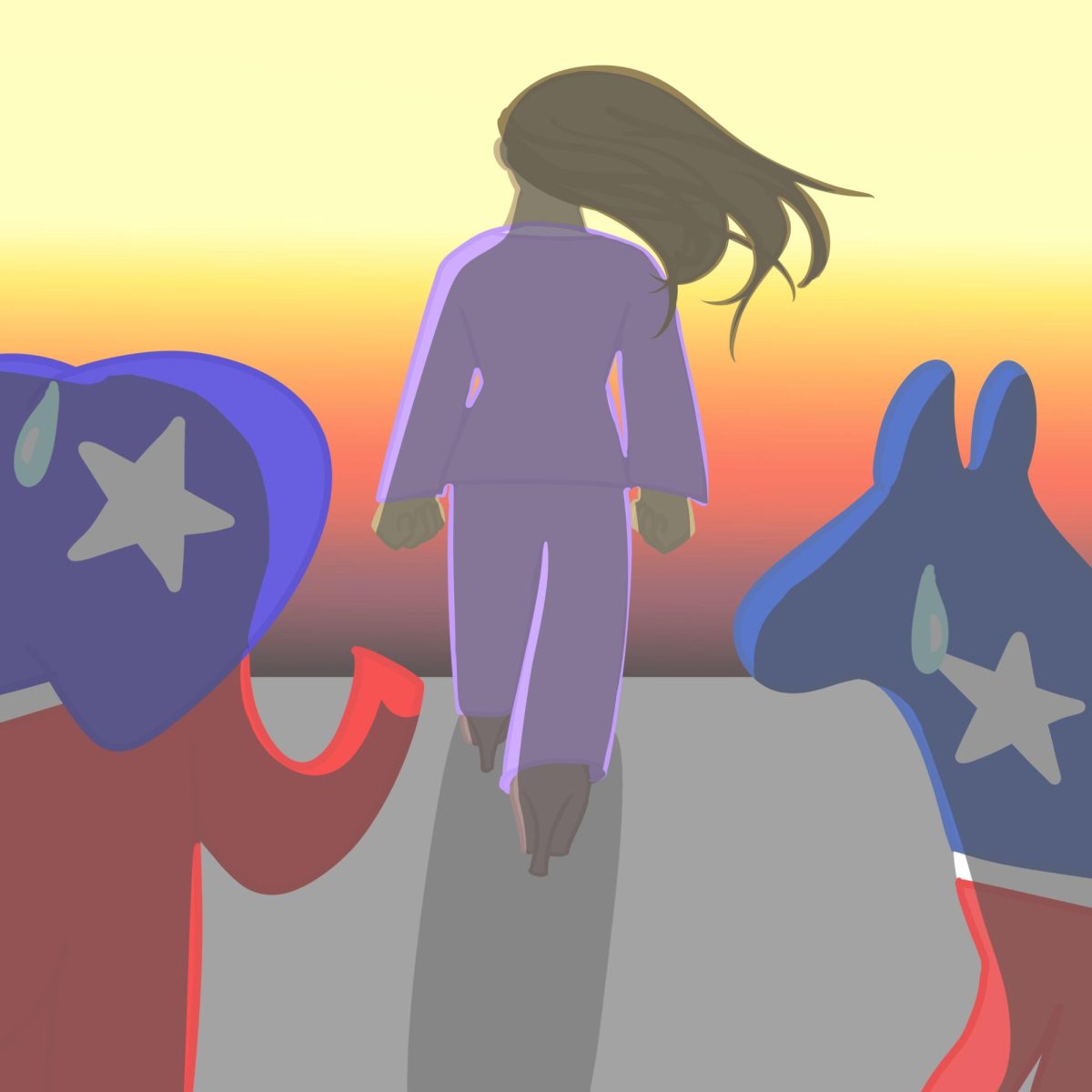

I take the bus regularly to go to work, get groceries and generally travel around the city. My concern lay with the MVHA’s invitation detailing there would be increased “safety issues” with the proposed changes. “Safety” in this case, regarding a rich white neighborhood, is oftentimes a code word for ensuring that poorer majority Black and Latino people stay out of it.

San Antonio has a long history of segregation in its design. COSA was surveyed in 1935 by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation for mortgage and foreclosure rates, where they concocted two notable maps: one was of the city’s “racial concentrations,” while the other depicted the HOLC’s devised “grades of security.” It just so happened that areas labeled as Black and Latino-inhabited were almost entirely within the “dangerous” prospective investment zones. The effects of this practice, known as redlining, remain in the stark economic contrast white neighborhoods like Monte Vista have to areas such as the west and east side.

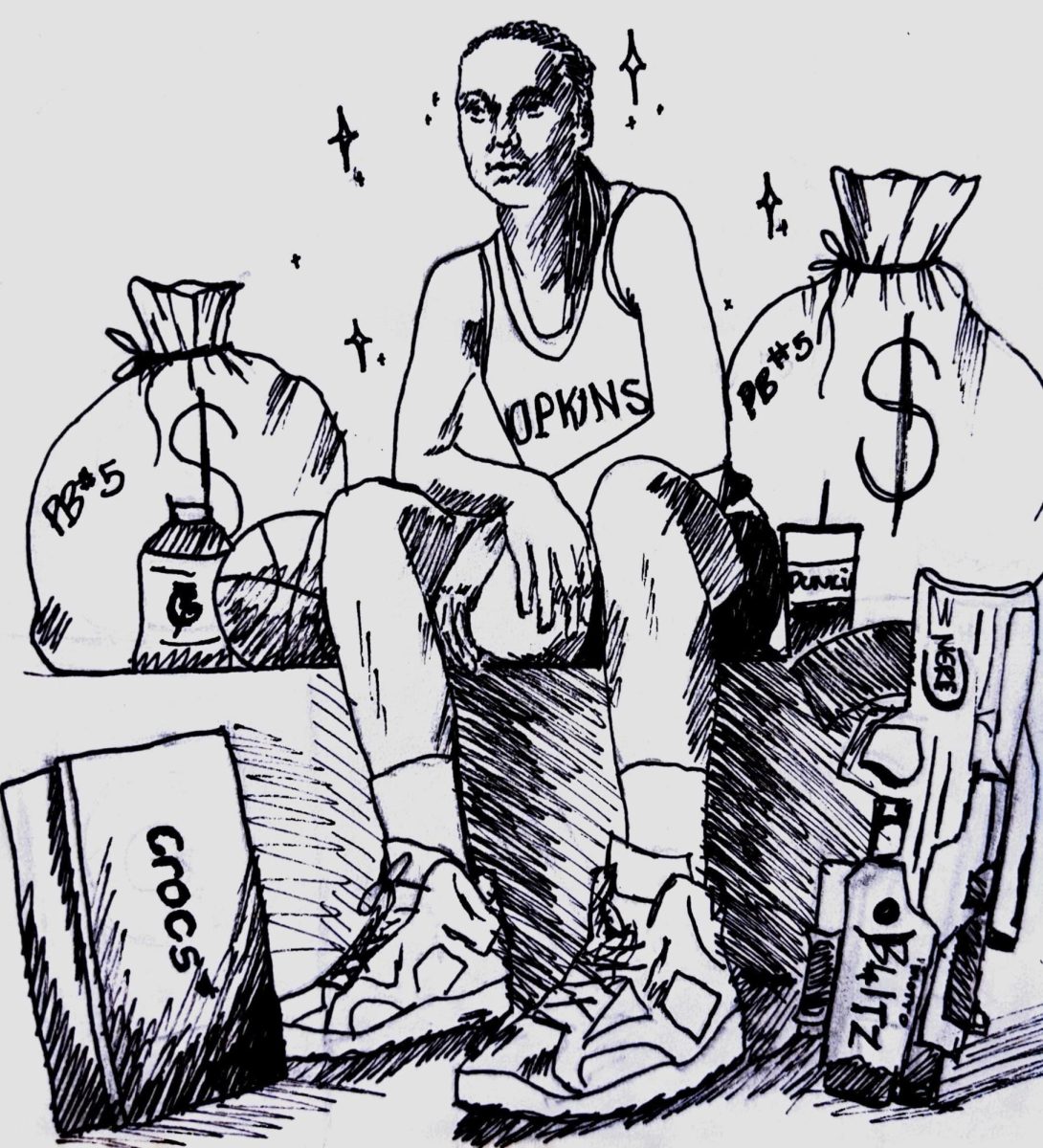

The representatives from the COSA transportation department and VIA attempted to explain the anticipated changes. Currently, the Transportation-Oriented Development (TOD) code is quite lenient; any building within half a mile of a bus stop is eligible to be classified under TOD zoning. Cat Hernandez, director of the transportation department, stated the idea is to update only the zoning code, “build those gateways,” to make the language less vague.

Meanwhile, VIA is about to conduct construction on the Green Line bus, which they estimate will double line three and four’s capacity from 4,500 to 8,000, and will have dedicated lanes for buses and right-turning vehicles.

Despite the neatly organized agenda, only half of the presentations were addressed due to one key flaw: allowing residents to respond in between the two acts. In short, the town hall meeting ended up being mainly about the bus line, with long ignorant comments from residents. Regular town hall attendee, Jack Finger, opened the floor by claiming the Green Line was a “power grab” by VIA, to “get people out of their cars” and squander their “flexibility.” Other complaints were about traffic increases due to the lane changes and potential parkers on the curbs.

Some workers who lack cars have to take one to two hour-long bus routes as their commute, as reported Arturo Herrera, Special Projects Manager of VIA. Residents of Monte Vista do not have this predicament, therefore they can deem the bus lines unnecessary. They have been diligently waited upon by the city for so long that when the focus is in any way taken off of them, they cause a fuss.

I’m here to remind Monte Vista residents that they’re not the only ones who live in San Antonio. Many of my fellow riders are the elderly and rely on public transport daily to get to important places. Monte Vista’s “heritage” is based on blatant and racist divisions that they are all too proud of, and the choices the city makes to move past them and improve the lives of its citizens will live on long after you are gone. Memento Mori.