Trinity University’s second Lennox Seminar lecture took place Monday, Oct. 2, in the Fiesta Room from Craig Williams, professor of classics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Williams’ work focuses on stories of animals, humans and love in and around the time of the Roman Empire.

“I focus on literary texts that speak of animals loving us, specifically falling in love with us,” Williams said before joining the audience in slightly uneasy giggling. The packed room was soon informed that this was not an odd theme in historical documents. Outside of the 31 ancient texts Williams has discovered over the course of his work, contemporary literature has also described love between animals and humans.

Author Jack London’s “The Call of the Wild” has enthralled readers since being published in 1903. Its protagonist Buck is a simple ranch dog that is stolen from his home in California and sold into the sled dog industry of Alaska. Before Buck becomes a feral wilderness leader, he is briefly cared for by a man named Jack. His love for the man is described like a love affair: genuine, passionate, feverish and burning.

According to Williams, there is a great deal of classical influence behind this moment from London’s novel. In Greek texts, the word used for this love is “˜Eros,’ which refers to intense desire for food, drink and sexual or nonsexual companionship. The Latin texts refer to burning, passionate love influenced by the deities Venus and Cupid.

Surprisingly, these texts are not fables or myths, but anecdotes. It is always the animal who falls in love with a human, who is emphasized as being young and beautiful. These are usually love stories without copulation.

Williams referenced Pliny the Elder’s “Natural History,” Aelian’s “On Animals” and Oppian’s “Halieuticks.” Reviewing 31 texts, Williams has tallied accounts of 10 dolphins, six birds, five elephants, two dogs, one ram, one horse and one seal explicitly showing love towards humans. Behaviors of note include courtship, physically affectionate touches and caresses, pair bonding, attempts at co-parenting and brief hints at sexual contact.

“Mutual love does not require reproduction,” Williams said, as many of these stories describe interactions between male animals and adolescent boys.

So, what do these stories even mean and what was the point of their preservation? Williams says that it’s all about power. Though they date to before and after the Roman Empire, the Romans compiled these stories in many of their texts investigating the natural world. True or not, the phenomena truly puts man at the top of the natural world as the epitome of biological perfection.

Anthropocentric themes are heavy in Roman literature. Political leaders were heralded as glorious bulls; a famous love poem by Anacreon refers to a boy with a girlish glance that holds the reins to the author’s heart; Pliny the Elder wrote that man is an animal destined to command others. Williams believes these stories speak to this idea of natural superiority.

But what about love?

“Eros is irresistible,” Williams said. Eros is laden with joy, pain and tragedy; these stories are as much about love as they are about the natural world. Love that sees no physical boundary.

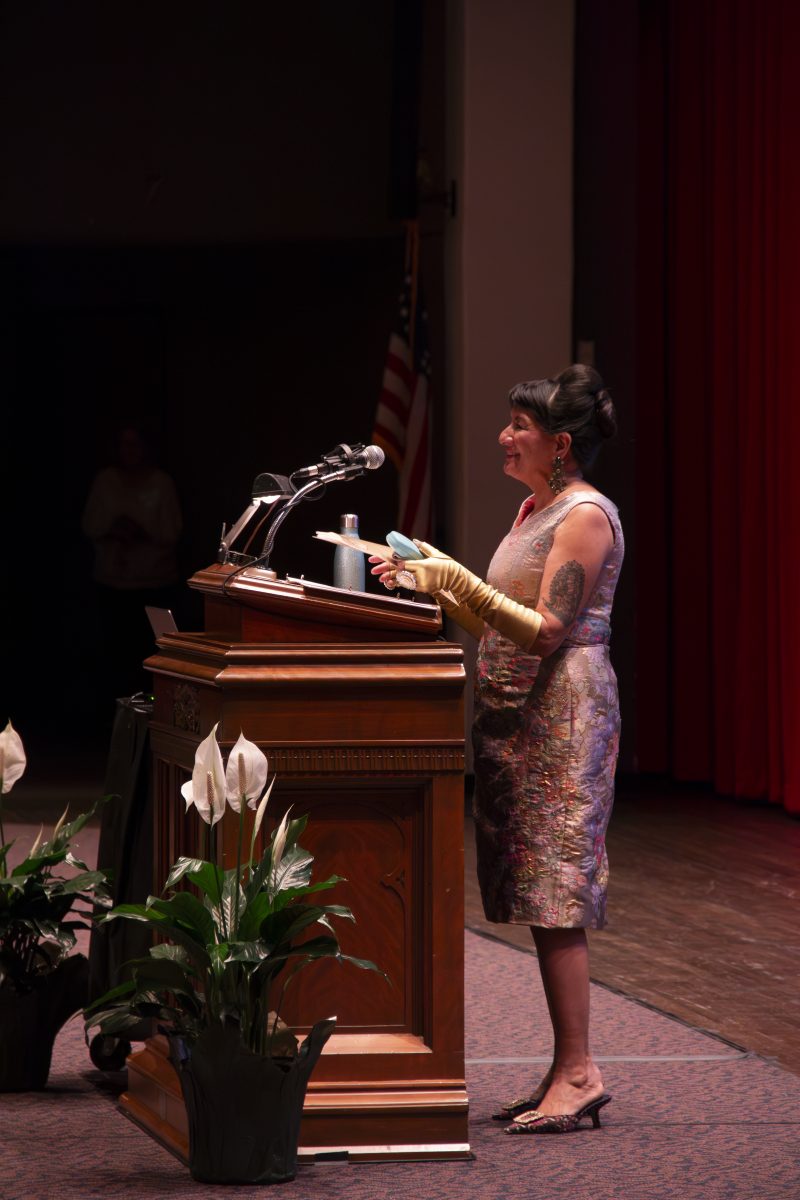

The previous Lennox Lecturer, Caroline Vout, university reader of classics and fellow at Christ’s College at the University of Cambridge, spoke on how sexuality is a force that transcends societal constraints. The Romans are well documented as having sexual and romantic relationships outside of the male-female binary. Williams certainly seems to echo Vout’s idea, that sexuality is enigmatic but intrinsic to life and culture. To know more about the Romans, we shouldn’t be afraid to talk seriously about sex and love.