Students, faculty, staff and assorted lecture attendees filled every seat and parts of the floor within the Chapman Great Hall the evening of Nov. 14 to hear Peggy Phelan speak as a part of the Stieren Lecture Series.

Phelan is a feminist scholar and a professor of English and theater and performance studies at Stanford University. In addition to a lengthy list of publication credits and chair positions, Phelan has been president of Performance Studies International and has won fellowships with the Getty Research Institute, the Stanford Humanities Center and the Guggenheim. Andy Warhol is the latest subject of her performance research.

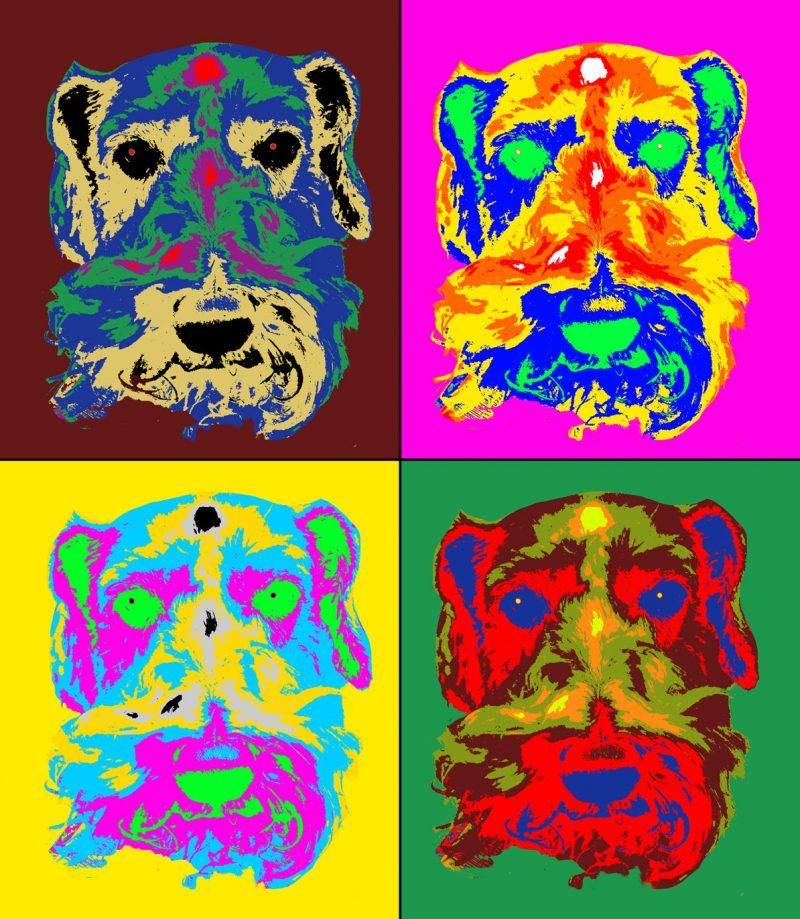

“Some 90 years after his birth and 30 years after his death, Warhol is still an enigma,” Phelan said as she flashed some of his celebrated pop art prints across the large screen positioned at the front of the room.

Warhol produced almost 10,000 silk screen prints in his career, in addition to photographs, conceptual sculptures, short films, philosophy, TV and experimental works. The iconic repetitions of subject matter and speed of processing that became characteristic to his body of work created an unparalleled density of art pieces. Phelan discussed how he has become, simultaneously, one of the most beloved and hated artists in art history because of this.

“Great art is above all coherent and approaching mastery,” Phelan said. “Warhol rips holes in these conceptions.”

She asked the audience to consider, as some of his critics did, “Can such an influential artist actually be good?”

Although Andy Warhol wrote and thought philosophically, he embraced a degree of stupidity and silliness into his work. He repeatedly questioned rather than solved concepts like death and capitalism, and his passion for repetition, as Phelan puts it, “assaults” art history because it challenges every aspect of the status quo within art history.

Phelan goes on to discuss more themes of repetition that became pervasive in Warhol’s personal life. In 1967, he was invited on a university tour. After a handful of stops he began to send an actor in his place. This foray into performance is often overlooked. When universities discovered the actor wasn’t Warhol they were outraged and began wondering if the man who had spoken at their events had been genuinely Warhol.

Phelan compares these various theatrical performances to Ronald Reagan’s campaign for governor of California. When asked what kind of politician he would be he famously replied that he didn’t know because he “had never played a governor,” of course. When questioned about the actor, Warhol stated that his doppelganger had more to say than he did. Warhol seemed to enjoy exploring what is perceived as genuine along with his idea of repetition and multiples. Phelan then prompted the audience to consider what it meant to buy a Warhol.

“Do we buy the art made by the person, or do we buy the person that made the art?” she asked.

Phelan then introduced the audience to Warhol’s lesser-known photographic endeavors. Stanford University has come into possession of some 130,000 black and white film exposures. Warhol shot a whole roll of film a day every day for the last 11 years leading up to his death. None of these photos were ever taken in his own house, but in social and studio settings. These effectively document the elusive last years of Warhol’s life. Before his unexpected death, it appears that he was only trying to work faster and in larger quantities.

The exposures are in the form of contact sheets, which are the first products of film development. Once film has been taken out of the camera and properly exposed, they can be printed in rows on a single sheet of photo paper so the photographer can see all the images captured on a roll of film in one place.

Warhol’s contact sheets by themselves are almost a work of art, and in true Warhol fashion viewers are exposed to a great deal of subject repetition, but the contact sheets also display self-portraits, behind-the-scenes glimpses and outtakes from famous silkscreen prints. Phelan and her colleagues are currently in the process of constructing an exhibition based entirely on the contact sheets.

“We’re seeing a capacity to go from contact sheets to Polaroid prints to silk screen, and sometimes to skip the steps altogether and go straight to the silk screen,” Phelan said.

The contact sheets gives us a new perspective of the artist’s process.

Decades after Warhol’s death, we are still finding work and learning about his artistic process. He authored some of the most iconic imagery in American pop culture, disrupted the art scene and continues to ensnare the art world today with wit, provocation and repetition.