Grace Cline spent three full semesters at Trinity, and she liked it here for the most part. She had great friends, she appreciated her professors and how much they cared about her as an individual, she was a member of the Jewish Student Association (JSA) and she even found a way to incorporate her passion for rock climbing into her San Antonio life.

She had plans to join a sorority. She expected her psychology degree would lead to grad school, and then eventually a career as a therapist.

The Trinity environment, with its competitive rigor and sometimes clique-laden social scene, was sometimes a tough challenge for Cline. But it was nothing she couldn’t handle. At least, that’s what she told herself.

About three months ago, however, Cline made the decision to permanently withdraw from Trinity for mental health reasons. She now resides in Austin and spends the hours that she is not working at a climbing gym hanging out with friends and finding new hiking trails to explore. Her new life may seem simple, but Cline loves where she is.

“I’m really happy and at peace right now. I haven’t felt that way in months,” Cline said.

Cline is not representative of every student who struggles with mental health or who takes a permanent withdrawal. However, Cline is not the only student to decide they would be better off away from Trinity.

A SLOW REALIZION

Cline said she had a great first year at Trinity, so it came as a surprise when sophomore year wasn’t going the same way. During her first year Cline was, for the most part, content. However, sophomore year represented a slow decline in Cline’s motivation and happiness.

As Cline’s anxiety and depression intensified, she began to wonder if college was a contributing factor.

“I guess I was kind of in denial that Trinity was part of the problem. I kept thinking, ‘Oh, it’s other stuff.’ I just need to fix — like, once I join a sorority or once I make new friends, or XYZ, it’ll be fine, I’ll get better. Because I loved Trinity my freshman year, so I kept wanting sophomore year to work out that way,” Cline said.

At her lowest point, Cline’s depression led to hospitalization. While she was in the hospital, she was also diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Still, Cline expected to make a full recovery and return to her Trinity life.

“While I was there, I was saying to myself, ‘Yeah, I’m gonna go back to Trinity. I’m gonna work on this, my professors are gonna help me and I’m gonna be fine.’ I finally had a family friend tell me, ‘Do you really like Trinity? Or do you want to like it?’ ” Cline said.

Hearing that question was a revelation for Cline.

“I guess it kind of blew my mind. Because once she said that, I was like, ‘Holy shit, you’re so right. I don’t actually like it; I just want to like it so bad,’ ” Cline said.

In truth, Cline was beginning to find the Trinity environment toxic. Aspects that she had previously appreciated about the university were becoming restrictive: the once-cozy smallness was now claustrophobic, and the once-exciting academic challenges now looked overwhelming and competitive.

She felt like few people recognized her mental issues as serious, simply because her symptoms were so common among Trinity students.

“Another thing was just the environment of competition,” Cline said. “Like, who’s more stressed. If I told somebody, ‘Hey I’m really struggling, I’m depressed’ — or anxious, or fill in the blank — the other person would respond with, ‘Oh, I’m stressed too, I’m taking 18 hours!’ It was just a competition. You’re not doing well unless you’re sacrificing your sanity a little bit.”

Even though Cline had always been a good student, by early January she lost all motivation to complete schoolwork.

“I didn’t have motivation to read, to do homework, to study — I just could not do it. And that’s never been me,” Cline said.

Soon after, she spent a full week in the hospital, and began to realize that she needed to make a major change in her life.

DECIDING TO LEAVE

Deciding to take a break from college wasn’t easy for Cline. She’d always thought that dropping out of college was a sign of weakness.

“There is that stigma, like, if you drop out of college, you don’t have it in you. Even I had that bias toward people who dropped out of Trinity, until I dropped out,” Cline said.

In addition, Cline’s family was overwhelmed upon hearing of Cline’s intense struggles with anxiety and depression. Though Cline was first diagnosed with depression in 2011, she was good at putting on a positive face, never letting her family know the extent to which her mental illness inhibited her.

“For me, it was like a slow train wreck all year. But for them, it was all at once — I was in the hospital, I was having to go to counseling every day,” Cline said.

After she got out of the hospital, Cline returned to Trinity to try again. Her father flew in to San Antonio from North Carolina in order to ensure that she would have a support if anything went wrong.

Cline found herself crying between classes, unable to get better. Upon witnessing Cline’s struggles firsthand, her father understood that a break might be the best decision for Cline.

“That first day back at school, I went to classes, and immediately I was a mess. I was an emotional wreck. I was crying between classes … I realized, ‘Oh shit, I just put myself in the same situation that got me to the hospital.’ For my dad to see me like that, instead of just hear me talk about it, I think really opened his eyes,” Cline said.

Cline filled out the transfer paperwork on Feb. 9 of this year. After leaving school, she moved in with her aunt in Austin, and got a job as an instructor at a local climbing gym.

Cline says she loves her new life and does not regret leaving Trinity in the slightest. These days, she usually works in the evening — or occasionally the morning or late afternoon — for about six to eight hours. The rest of the time is hers.

“It’s a lot of downtime by myself, which I don’t mind. I like it. It’s a lot of, like, finding the coolest hiking spot. The other day, I went swimming in Barton Springs without planning on it: I was just hiking, and there were these dogs swimming, and I was like, ‘I want to get in the water with them,’ ” she said.

Grace Cline spends her days working at a climbing gym in Austin. photo provided by Grace Cline.

THE BIG PICTURE

According to vice president for enrollment management, Eric Maloof, students who take a temporary or permanent withdrawal from Trinity typically do so after their first year and before beginning their sophomore year.

A cohort study of the class of 2020 showed that 73 students of the 660 who started as first-years in Fall 2016 did not return for the Fall 2017 semester. Of these 73, 51 went to public institutions, 7 went to private institutions, and 15 were not found by the research institution, National Student Clearinghouse.

Though the 2020 class is only one cohort, Maloof said that the data from that year is relatively typical. Over the last three to five years, Trinity has retained approximately 90 percent of students between the first and second year.

“Compared to a lot of our competitors, 90 percent is a fairly strong number,” Maloof said.

But there will always be that approximately 10 percent that leave after a year, not to mention even more students like Cline who withdraw during a subsequent year. The decision to withdraw tends to be a permanent one.

“Some of those students come back; the majority don’t,” Maloof said.

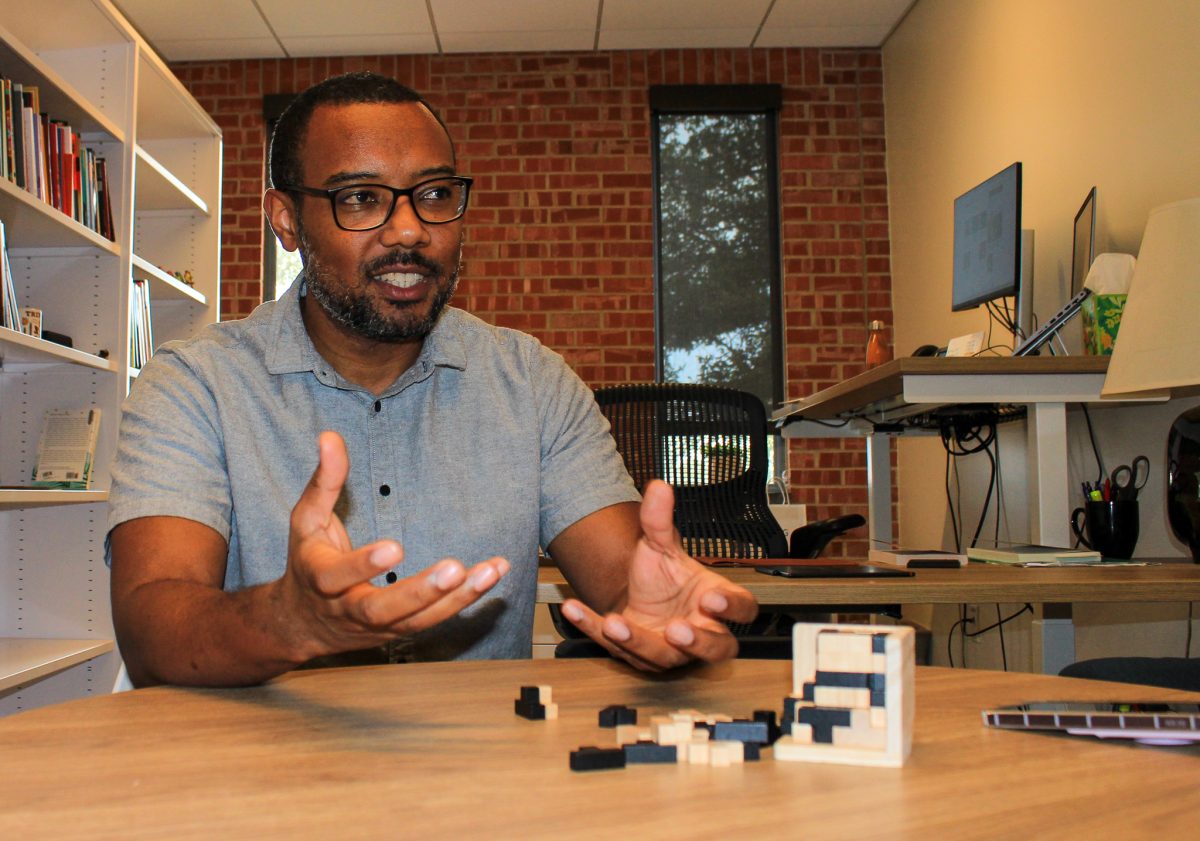

Of course, each student has a different reason for leaving. Mental health is certainly not unheard of as a cause for withdrawal, according to associate vice president for academic affairs, Michael Soto.

“Most students who come here are aware of the academic challenges that they face, and if they’re admitted to Trinity, they are capable of meeting those challenges, but there are times when physical or mental health changes prevent them — at least for the time being — from fully rising to that challenge … It’s not uncommon,” Soto said.

Cline firmly believes that there is no shame in dropping out, and said that no one should be afraid to withdraw if they feel it is the right choice for them.

“There really is nothing wrong with it,” Cline said. “You’re going to be okay. So many people — so many successful people — have dropped out of college, or dropped out of college and went back.”