This October marked one full year since I returned to the religion I grew up in but left for many years: the Catholic Church. It has been a year full of learning, growing and experiencing Catholicism in ways that I never expected.

The large neighborhood parish I grew up in was familiar and comforting but never really allowed me to see the wide berth of of culture which exists in Catholicism. Nearly all the families who went there were either white or Hispanic, and masses were offered only in English or Spanish. Behind the altar stood a European-style mural and simple felt banners aligning with the liturgical season were hung from the ceiling.

Going to Mass at Trinity was much of the same, and it filled me with a feeling of familiarity that I had missed for many years. However, I have quickly come to realize that my American taste of Western Catholicism was only a small drop in a mammoth ocean filled with cultures far beyond those typically thought of as Catholic.

I experienced it this weekend as my boyfriend and I attended the Lebanese Food Festival, hosted at St. George Maronite Church in San Antonio. We walked around, ate za’atar man’oushe (a Lebanese dish of flatbread with herbs and spices), watched young men and women perform traditional Middle Eastern dances and conversed with a woman advertising classes she was teaching in Arabic. This was all Catholic and all a fundraiser for the parish.

Beyond being a fun evening spent eating delicious food and listening to great music, going to the Lebanese Food Festival also opened my eyes to yet another branch of culture in a Church I felt familiar in. These were all people who practiced the exact same faith as I did in a completely different — yet still utterly beautiful — way.

I also felt this when I began attending services at a Byzantine Catholic community, which my boyfriend had been attending for the year prior. This led me to spending most of my summer at home going to Divine Liturgy at another Byzantine church, as I desired to learn more.

The church I went to was immediately different from anything else I had ever experienced, as it was covered in rich icons of biblical figures and saints, many with names I had never heard before. Incense filled the small sanctuary, and many of the women wore headscarves, similar to a Muslim woman’s hijab. These scarves were only worn during Divine Liturgy and are the Eastern equivalent to the traditional chapel veil of the West.

These examples are neither rare nor difficult to find here in the United States. A Syro-Malabar church is within walking distance from my home in Dallas, which is attended by hundreds of Indian Americans who go to liturgical services in their native tongue of Malayalam. San Antonio is also filled with many of these churches, with small communities of believers all sharing in their own diverse cultures.

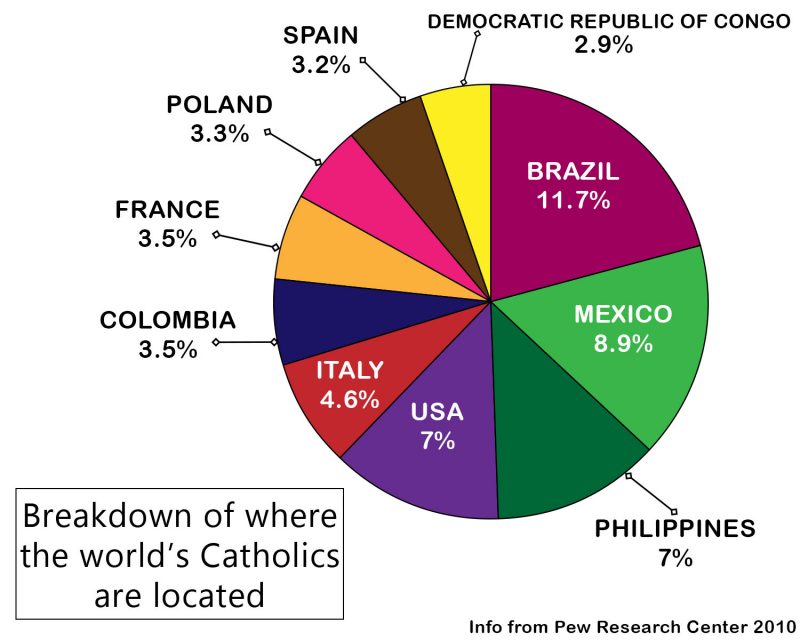

This is exactly why it isn’t uncommon to see renditions of the Virgin Mary and Jesus as a multitude of races. Italian or German paintings may show them as fair-skinned and light-haired, but Koreans will often depict them as Koreans and Africans as African. It is the reason why the Marian apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe was a native woman, and John Paul II canonized a Native American woman (Kateri Tekakwitha) as a saint. It is the reason why the Catholic Church is growing at the fastest rate in Africa and many in the Vatican see the African people as the new generation of Catholics.

It is because Catholicism is not just for one race or one culture. It is a church meant for all — exactly what Christ meant when he said to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19). The word “catholic”, after all, simply comes from the Greek word katholikos, or “universal”. As members of this universal church, I believe we owe it to ourselves to experience the vast cultures that all profess our same creed but live it out in their own unique and beautiful ways.