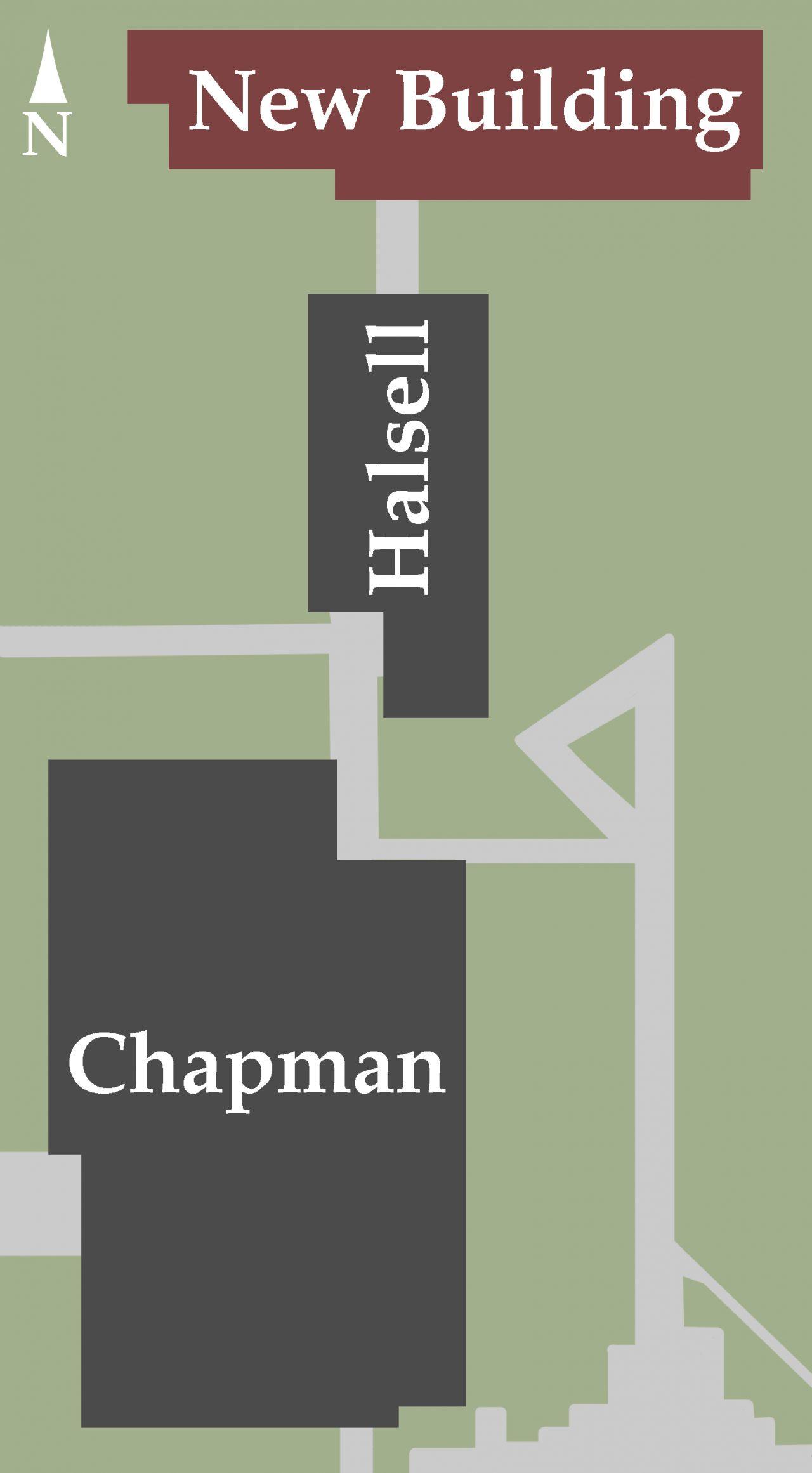

Construction on the Chapman-Halsell Complex is slated to begin this summer after months of consulting with architects and committees of faculty and staff. The construction will mean interior renovations for the two existing buildings and the construction of a new building north of Halsell.

ARCHITECTURE AND CONSTRUCTION

In 2017, the university released a campus master plan that includes the construction on a Chapman-Halsell complex. Construction will take place over three years in two 18-month phases.

The first phase describes renovations to Halsell and plans for a new building, and the next phase focuses on renovations to Chapman.

While committees of faculty and staff advised the project, Lake Flato Architects, designer of the outdoor spaces at Pearl, spearheaded the design phase of the project as a whole.

“Right now, the architects have finished what’s called [a] schematic design, and so that’s kind of a general sense of what’s going to be located where, how many classrooms there will be, general principles of how they want the buildings to operate,” said Tim O’Sullivan, classics professor and co-chair of the faculty committee for the project. “Now, they are working on transitioning to actual construction documents, things that will be given to contractors to plan construction.”

While the new building will include red brick, one of the major building materials will be cross-laminated timber (CLT), which will be partially exposed on the inside of the building. The material parallels the innovative nature of architect O’Neil Ford’s original design.

“Trinity started with the lift-slab concept, which got O’Neil Ford lots of attention and Trinity lots of attention from architects across the country. So in that spirit, our new building is going to be using a new product called CLT, or cross-laminated timber. So the structure of the building, rather than being concrete or steel, is going to be wood. It’s a new system, there’s one building in SA that I know of that’s about to be under construction using CLTs, and so we may be the second one here in San Antonio,” said university architect Gordon Bohmfalk.

Construction on Chapman and Halsell is constrained by the building’s historic status, which requires that the exteriors and certain parts of the interiors do not change.

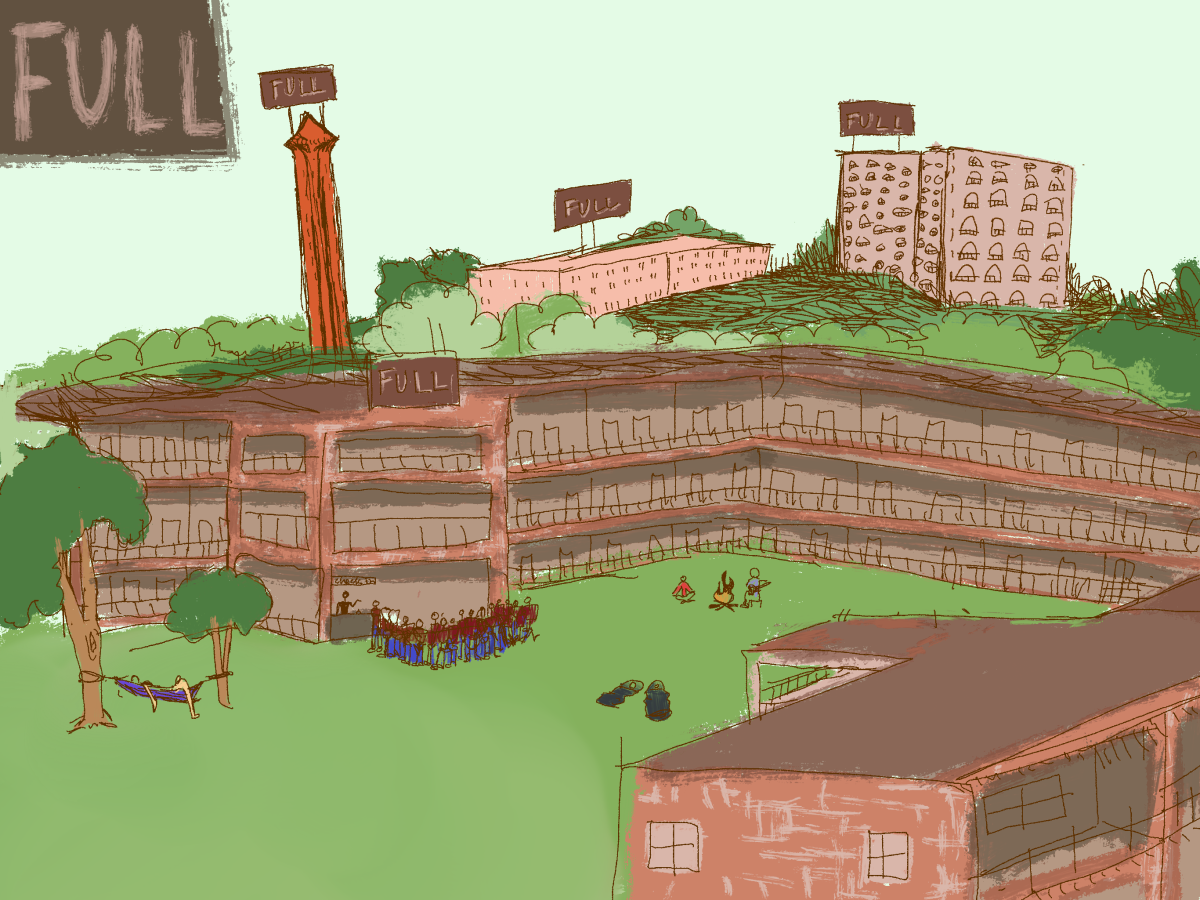

“In the Great Hall, they will change three of the windows into doors, and the Great Hall will become a student common space. Right now, there’s that really beautiful walkway between Chapman and the library, but it just kind of ends in a parking lot, so this is going to end in the eastern facade of the new building, and so there’s a chance to create some green space for students to gather,” O’Sullivan said.

The master plan also shows a new entrance off of Hildebrand Ave., which will lead to a new welcome center with a parking garage located north of Laurie Auditorium. Currently, the spaces that will be occupied by the new building, the new courtyards and the future welcome center are parking lots.

Bohmfalk assured that parking is something that they are considering. However, during the three-year construction period, parking will be reduced.

“There’s a reduction in parking up there for Chapman and Halsell. It’s maybe temporarily an inconvenience, but it’s done for the right reasons because we are creating these new courtyards,” Bohmfalk said. “Hopefully by that time, we will have made progress in our planning for the welcome center, which includes a below-grade parking garage and will not only serve the campus but the 2700-seat Laurie Auditorium.”

ACADEMICS

The Chapman-Halsell complex will eventually house 10 academic departments. The Department of English will move from Northrup Hall to the new building, while the Center for International Engagement, which includes the Office of Study Abroad, International Student Services and International Studies, will move to Northrup. ITS will also move from their Halsell offices to an existing building on the Oblate property, a lot on Shook Avenue and West King’s Highway that the university purchased in early 2017. The new building will also hold the Department of Religion, as well as a space for the Mellon Initiative.

“So, desire one is to make sure that they have departmental spaces adequate for their needs. But of course, Chapman serves the entire university,” O’Sullivan said. “So the main thing we heard was that people want classrooms that are more flexible and that allow for not only a greater variety of pedagogical styles, but more specifically, more interactive teaching styles. And to do that, basically, you’re talking about a need for more space.”

According to O’Sullivan, the current standard for flexible classrooms in newer buildings is around 30-square-feet per student. The average size of a Chapman classroom is around 18-square-feet per student.

“That’s the main driver really for the new building. There’s not actually going to be much more space for departments; in fact, some departments might have the same or a little less space,” O’Sullivan said.

The new building will have six classrooms that hold around 35 students and can be used by any university department. The classrooms will have higher ceilings than those in Chapman and Halsell, which will allow instructors to project images and write on a whiteboard simultaneously.

There will also be a screening room that will hold around 70 students for classes that are centered on film or for student film groups. There will also be a small lecture hall, which O’Sullivan compared to Northrup 040. This will be used for Common Learning Experiences in the First-Year Experience (FYE) courses, as well as by speakers.

“There’s also been a perceived need for more rooms that will host seminars, particularly the FYEs, so there’s going to be five or six classrooms that are designed for a capacity of around 20. It’ll be flexible,” O’Sullivan said. “The idea is that it can host a good discussion around a table, but those tables are modular, and you can move into different arrangements.”

FUNDRAISING

Fundraising for the Chapman-Halsell complex project is under the charge of Michael Bacon, vice president for Alumni Relations and Development.

“At this point, we’ve been trying to put together materials to describe the project to put out and share with the donors to get them excited about it,” Bacon said. “The project is so early on that there hasn’t been a whole lot of fundraising that has happened yet because we can’t develop those materials until the architects finish their drawings. I think they just finished in November or December, so we’ve been hard at work trying to come up with something that we can share with the donors to see if they are interested in investing in the project.”

Of the estimated $77-million cost of the project, $35 million will come from the Chapman Trust and six to eight million dollars will come from historical tax credits earned through sustaining the historical aspects of Trinity’s campus in the construction. This leaves around $35 million left to raise. According to Bacon, the university aims to fund the remainder with gifts from donors of at least $100,000.

“It’ll take us a couple of years [to raise all of the money], quite honestly,” Bacon said. “We might have a conversation with [a donor] tomorrow, but they’ll take three to five years to pay it off because most people when they make a gift, they can’t write the whole check at once, so they spread it out over a couple years. Trinity then has to do interim financing, so we can build the building or renovate the building now and then use the pledge payments to pay it off over time.”

Bacon also noted that the fundraising timeline is different from the construction timeline.

“Ideally, you’d love to have the fundraising started well before the construction timeline,” Bacon said. “This has just been one of those projects that has just been so important to the campus. Two reasons: one, everyone wants to see it happen, and two, the longer we wait to get it started, the more the costs increase in terms of steel, concrete, construction costs. You can push the pause button on this for two years, but then the project will be a third more expensive.”

SUSTAINABILITY

According to Bohmfalk, one of the goals for the new building is to make it the most sustainable building on campus. However, this does not necessarily mean that the building will be LEED certified.

“The question about LEED certification has come up, and right now, I think most are of the opinion that we are more interested in achieving the goal of being the most efficient building on campus … rather than spending the money on a third-party certification,” Bohmfalk said. “It hasn’t been completely decided yet, but those kinds of certifications cost money and add to the budget.”

Aspects of the new complex, such as the landscaping of the new courtyards and the specific materials that are used in construction, will contribute to the sustainability of the building. The natural light and the use of wood is important for human health, according to Bohmfalk. The entire complex will also integrate with CSI’s greywater use program, where water is recycled and reused.

“[CSI] actually produces more greywater than it uses, and that means that the greywater is going into the sewer. So rather than use perfectly good drinking water to flush toilets, we’ll use the greywater. And so the greywater from our new mechanical systems in the new building and the older buildings will tie into that [system],” Bohmfalk said.