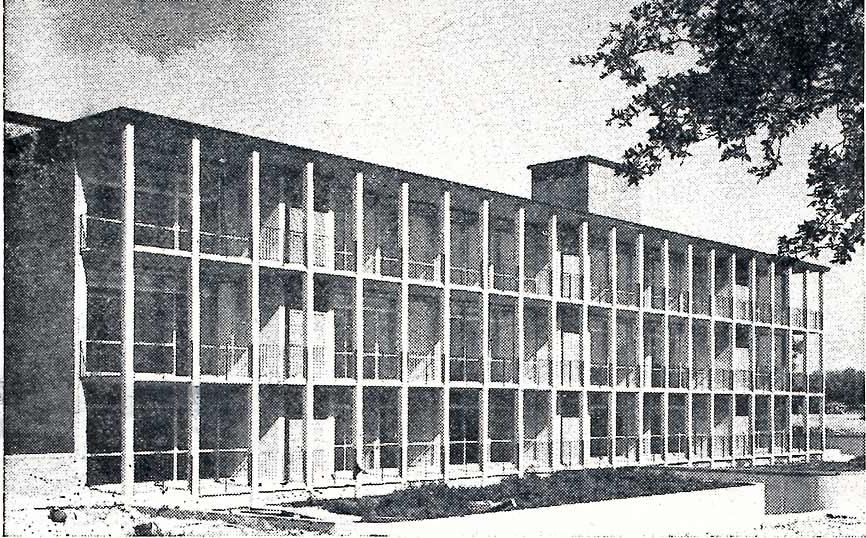

Chapman Center, originally named Chapman Graduate Center, was formally dedicated on May 29, 1964. First conceived as a building for Trinity’s emerging graduate student population, the original plans for the building included separate floors for faculty, students and research projects, a four-floor gr aduate library with space for 250,000 volumes and even a coffee lounge for students and faculty.

While the building has since transitioned to an academic building for undergraduate students — with departments such as philosophy, business and history coexisting under one roof — the upcoming Chapman renovation aims to rejuvenate a historic building.

Chapman’s creation

In 1962, Trinity benefactor and philanthropist James A. Chapman agreed to build a $1.5 million dollar graduate center for Trinity’s growing graduate student population in honor of his parents, Philip and Roxana Chapman. The building was constructed by architects O’Neil Ford, Bartlett Cocke and H.G. Barnard Jr. — a personal friend of the Chapman family.

O’Neil Ford — who designed several buildings at Trinity — had an enormous influence on Chapman’s design, according to Carolyn Peterson and Rachel Wright, two members of the Ford, Powell & Carson architectural firm.

“[Ford] was also very much part of a group of people west of the Mississippi, who believed in taking modern architecture and expressing it [by] using regional materials and even shapes and things that are more related to the area you’re in,” Peterson said. “It was modern, but it has a [human element].”

Chapman Center was originally intended to be divided into two “volumes” — an extensive undergraduate library and another area devoted to classrooms.

Wright said that these intentions are the reason why the elevators on either side of the building go to different floors; this is also why the east side of the building has expansive windows while the other sides feature smaller ones.

“The building — historically the north volume, which is the taller one — was the graduate library, so that’s part of the reason it’s so enclosed. The east side [with] all the glasses, those [were] the classrooms which opened out onto the porches. The tiny windows, which we refer to as ‘monk windows,’ were directly related to the carrels that were in the library,” Wright said. “When you read the [historic plans for the building], you can see … you were supposed to be [studying] in your carell next to the window and having kind of this personal interaction [with the window].”

A faculty perspective

Nicole Marafioti, associate professor of history, appreciates both the floor-to-ceiling windows in the Department of History and the medieval aesthetics of the Great Hall, which Wright and Peterson speculate were influenced by O’Neil Ford’s frequent travels to Europe during the building’s construction.

“The Great Hall is one of my favorite spots on campus because I am the medieval history professor, and it is full of armor and weapons and tapestries and good medieval stuff,” Marafioti said. “It’s not really medieval … but the feel of [the environment] is, I suspect, meant to replicate a medieval setting.”

However, Marafioti identified several structural issues which she and other faculty members interviewed hope will be solved by the renovations.

“The entire building needs serious updating from things like simply bringing the electrical and WiFi stuff — the technology — up to current standards to things like layout,” Marafioti said. “Now that [faculty] spend a lot more time working on things like writing or having small group discussions, having the lecture hall layout is cumbersome … There are definitely concerns about mold in multiple departments, and some of the aging of the building is a bit troublesome from a health and safety standpoint.”

Perserving the old, adding the new

Because Trinity is now classified as a historic district in San Antonio, the planned renovations to Chapman will update the building while preserving its “character-defining features,” a term used by Wright and Peterson in their architectural work.

“We have defined at the exterior the building as a kind of a primary character-defining feature, meaning it has a lot of impact on the campus at large — any interventions that we do to the building should be fairly minimal along the outside,” Wright said.

“Character-defining features that on the inside [include] the Lynn Ford doors, light fixtures, large glass sliders and wood slats,” Wright said. “The Great Hall is identified as an exceptional space, meaning that all of the features in there are particularly important, so interventions will also be kept minimal.”

Ford, Powell and Carson will work alongside Texas architecture firm Lake Flato to renovate Chapman and Halsell along with adding a new building next to Halsell which will allow the departments to have more space. Faculty members have also been able to have a voice in the renovations process.

“We have a committee of six faculty who are drawn from the future inhabitants of Chapman, Halsell and the new building, and hundreds of hours of meeting time with ourselves and with the architects and other members of campus, especially going back to departments and talking to them about how they want the building to be [renovated],” said Tim O’Sullivan, professor of classics, who heads the renovations committee alongside Ruben Dupertuis, professor of religion.

“I think what’s neat about the new design is that they really take what’s most special about Chapman and really bring it to the forefront,” O’Sullivan said.